I sense that the tide is beginning to turn on the knowledge-versus-skills debate, ‘21st Century’ or otherwise. There is an increasingly confident voice shouting a phrase that teachers have shouted for the few thousands of years that there have been teachers: knowledge is really important.

Yes, even in this Googleable world, knowledge is important. We could patiently wait for the “importance of knowledge” pendulum to swing back, or we could, as evidence-informed professionals, boldly provide an epistemic nudge [1].

This post is a concise argument for the importance of knowledge, and offers some research informed ideas for teachers on how to build it.

I recently heard Robert Pondisco, senior fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, give a wonderful talk at ResearchED DC on the importance of a recommitment to teaching knowledge. During his talk, Pondisco eloquently painted the picture of President Obama during his first Inaugural Address, glancing down the length of the Mall to the Lincoln Memorial where Martin Luther King Jr. said those famous words not that long ago.

And then Obama delivered the words in this clip. It was a powerful moment in American history. And Pondisco posed the question: what knowledge would children need to have to understand the significance of these words at this moment? Would they have this knowledge? How would they have got in? Who might have it and who might not? How does this fit in the existing inequality gap? Pondisco’s questions offer a fascinating thought experiment into the importance of knowledge.

Acknowledge the limits of active working memory

Active working memory can hold fewer things for less time than most people realize. Though it is hard to measure, 7 things for 30 seconds for adults is a well agreed upon estimate [2]. For children the numbers are lower. And there is a trade off too – we can hold more things but for progressively less time.

How do these limitations fit my argument?

Having knowledge stored in long term memory frees up the active working memory to more effectively help with higher order thinking tasks. In other words, having stored knowledge helps us think.

Even project based learning needs knowledge

What about things like project based learning (PBL): the antithesis of the “lecture, lecture, test” mode of teaching? How important is it to be very purposeful in teaching knowledge when we want students to be on a voyage of independent exploration? It turns out that explicitly teaching knowledge in very deliberate ways is extremely important for PBL: make-or-break important, in fact.

I will tuck deeply into the deficiencies of PBL at a later date. But the crux of the research-supported argument is that for project based learning to have any measure of success, independent inquiry needs to be balanced with didactic instruction. Without foundational information, students lack sufficient knowledge and skills to be able to engage with the task.

In fact, failing to provide adequate support for knowledge and skills may actually contribute to the achievement gap, as students from disadvantaged backgrounds often enter school with deficiencies in knowledge and skills that are necessary for success in the project [3, 4, 5].

Part of pedagogical content knowledge, that highly interlinked combination of subject knowledge and how to teach it, is to know exactly what knowledge scaffolding students need in order to successfully launch into a project. So if we want to create great projects, which we do, we also need to be great at teaching knowledge – and great at discerning what knowledge that needs to be.

Teaching for stickiness

No matter where in the spectrum from direct-instruction-focused to project-focused we happen to be teaching, we need to get content knowledge to reliably stick in long-term memory. Fortunately there is robust research to guide us here. It suggests both things we should do and should not do.

Things Not To Do

(1) rereading notes

A trip down the aisles of Staples in August confirms what we already know – students love highlighters. But research suggests that the staple of studying, rereading notes or the textbook, is a terrible way to study. It tends to lead to what Brown, Roediger and McDaniel call “the illusion of fluency” [6], where students become so familiar with the text that they believe they know it before they actually do.

(2) misusing flashcards

Similarly, students tend to use flashcards in entirely the wrong way – which is hard for such a simple device. They tend to turn them over too quickly to see the answer. The key part is how one lingers in the moment of not knowing. The key part is the moment before you turn it over. Flashcards work best when students ponder difficult questions, even when the answers prove elusive.

Things To Do

(1) retrieval practice

Retrieval practice is this idea of trying to recall knowledge from memory. Even if a student is unable to, research suggests that the act of trying helps memory storage and recall. Retrieval practice can take many forms: self testing, proper use of flashcards or online tools such as Quizlet, or taking a sheet of paper and writing out everything you know on a subject.

But I am sure you can be creative and add to this list. The key is having students try deeply to recall, then having them check this against their notes or model answers.

(2) spacing

There is great research around the spacing effect. That is, students should study, leave a gap, then study again. We can, for example, coach students to space their studying rather than use massed studying. Massed studying does not lead to durable learning.

Instead, allowing your memory to get a bit rusty between study sessions makes the next study session more challenging. In doing so, it helps create knowledge that is both more durable and more flexible. This is a concept that Clark and Bjork call “desirable difficulty” [7].

But what is the optimal spacing gap for your students, your subject, and the content you are teaching? This is a great idea for you to play with and do your own disciplined inquiry. (You might check out Scott MacClintic’s forthcoming article on gathering classroom data for suggestions.)

(3) formative assessments

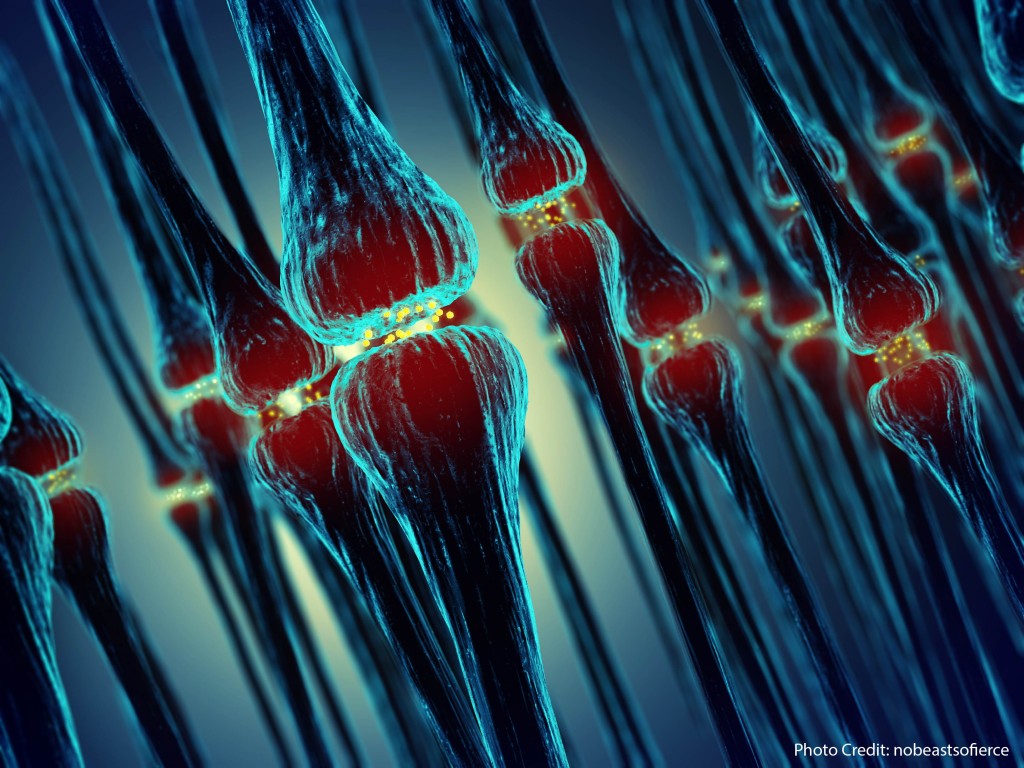

Replace pop quizzes with no- or low-stakes formative assessments. As you give these quizzes, say something along the lines of, “this is for you to figure out where you are, for me to figure out where you are, and for us both to adjust what we do accordingly.” This technique is retrieval practice plus. A further benefit is that more of the brain restructuring associated with learning occurs when we struggle and when we get things wrong [8, 9]. Getting things wrong is an important part of learning, and we need to craft no- or low-stress opportunities for this to happen.

(4) interleaving

Interleaving is a way to deliberately build the spacing effect into how you design your courses. Instead of starting the year with unit one, followed, perhaps, by unit two then unit three, there is an alternative way to organize things that will promote learning. After moving on to a new unit, plan on revisiting the core knowledge at least a couple more times at spaced intervals later on [10].

(5) pre-testing

“Research suggests that starting a unit of study with a pre-test helps create more enduring learning. It appears to give students something on which to hang subsequent information. This test should, of course, not be graded, or if it is, it should be graded for effort rather than correctness.

The other point of this pre-test is to give the teacher an idea of where the level of the class generally is, and what knowledge each individual student brings with them already, so that the teacher can tailor subsequent classes to best match the needs of the class. It is important to avoid seeding boredom, and to avoid the potential skipping of foundational knowledge that could prevent future learning. These are two common toxic effects on learning” [11].

A thought on how these suggestions link to assessment

Since a little kid, I have always enjoyed words. Some are more fun to play with than others, of course, but one of the best is ‘facile.’ We often use it to refer to someone who appears so good at something they do it with an effortless ease. But its more nuanced meaning is to refer to a demonstration of thinking that at first glance seems neat, concise and elegant, but which on closer inspection is only neat, concise and elegant because it is oversimplistic, itself lacking in nuanced details.

So this article, I believe, leads us to a future one that needs to be written: how do we avoid facile demonstrations of knowledge by our students? How do we craft assessments that steer students away from this? Or, as Rob Coe and David Didau put it, where will students think hard in this lesson? But in the time before this second article is written, I encourage you to explore this idea yourself. And if you have ideas as to what should go in such an article, please let us know.

- Thank you, Troy Dahlke, for this playful term

- Cowan, N. (2008). What are the differences between long-term, short-term, and working memory?. Progress in Brain Research, 169, 323-338. [link]

- Education Endowment Foundation Analysis [link]

- Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75-86. [link]

- Kirschner, P. A., & van Merriënboer, J. J. (2013). Do learners really know best? Urban legends in education. Educational psychologist, 48(3), 169-183. [link]

- Brown, P. C., Roediher, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Clark, C. M., & Bjork, R. A. (2014). When and why introducing difficulties and errors can enhance instruction. In V. A. Benassi, C. E. Overson, & C. M. Hakala (Eds.), Applying the Science of Learning in Education: Infusing psychological science into the curriculum. [link]

- See this accessible research summary from Robert Bjork at UCLA

- Moser, J. S., Schroder, H. S., Heeter, C., Moran, T. P., & Lee, Y. H. (2011). Mind Your Errors Evidence for a Neural Mechanism Linking Growth Mind-Set to Adaptive Posterror Adjustments. Psychological Science, 21(2), 1484-1489. [link]

- Blasiman, R. N. (2016). Distributed Concept Reviews Improve Exam Performance. Teaching of Psychology, 44(1), 46-50. [link]

- Whitman, G. and Kelleher, I. (2016). Neuroteach: Brain science and the future of education. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.