Kurt Fischer — who helped create Learning and the Brain, and the entire field of Mind, Brain, and Education — used to say: “when it comes to the brain, we’re all still in kindergarten.”

He meant: the brain is so FANTASTICALLY complicated that we barely know how little we know.

Yes, we can name brain regions. We can partially describe neural networks. Astonishing new technologies let us pry into all sorts of secrets.

And yet, by the time he left the program he founded at Harvard, Dr. Fischer was saying: “when it comes to the brain, we’re now just in 1st grade.”

The brain is really that complicated.

Fascinating Questions

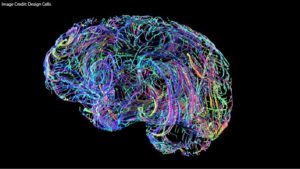

Adolescents — with their marvelous and exasperating behavior — raise all sorts of fascinating questions.

In particular, we recognize a real change in their ability to think abstractly.

Unlike their younger selves, teens can often “infer…system-level implications…and lessons that transcend the immediate situation.”

We can say in a general way that, well, teens improve at this cognitive ability. But: can we explain how?

More specifically, can we look a their brains and offer a reasonable explanation? Something like: “because [this part of the brain] changes [this way], teens improve at abstract thinking.”

A research team at the University of Southern California wanted answers.

Networks in the Brain

These researchers showed 65 teens brief, compelling videos about “living, non-famous adolescents from around the world.” They discussed those videos with the teens, and recorded their reactions.

And then they replayed key moments while the teens lay in an fMRI scanner.

In this way, they could (probably) see which brain networks were most active when the teens had specific or abstract reactions.

For example, the teen might say something specific and individual about the teen in the video, or about themselves: “I just feel so bad for her.”

Or, she might say something about an abstract “truth, lesson, or value”: e.g., “We have to inspire people who have the potential to improve society.”

If some brain networks correlated with specific/individual statements, and other networks with abstract/general statements, that correlation might start to answer this question.

As usual, this research team started with predictions.

They suspected that abstract statements would correlate with activity in the default mode network.

And, they predicted that concrete statements would correlate with activity in the executive control network.

What did they find?

Results and Conclusions

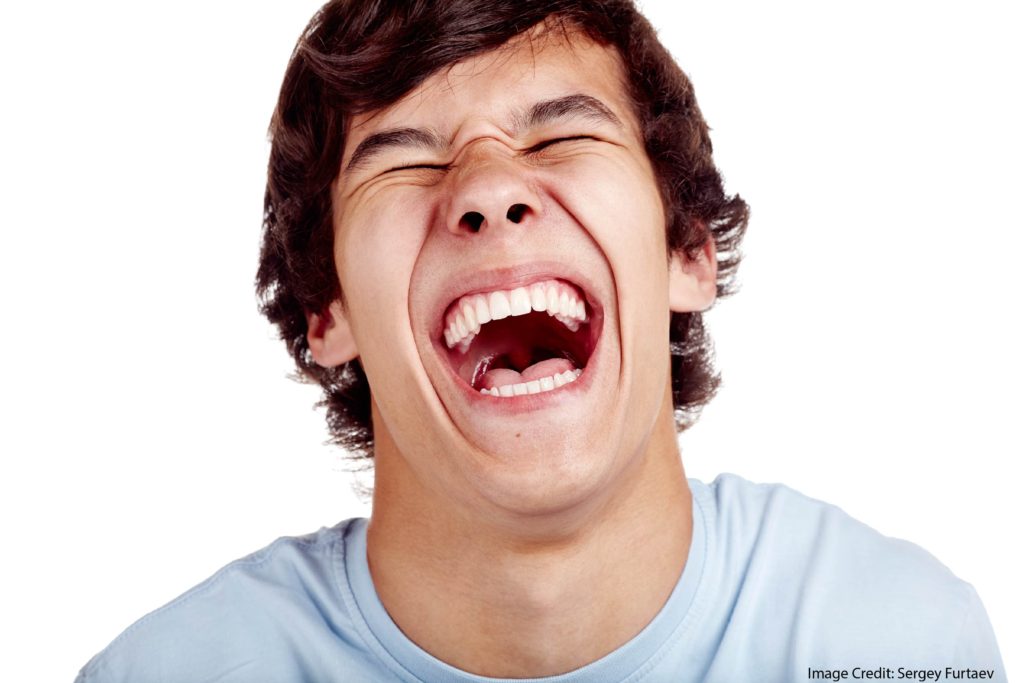

Sure enough, the results aligned with their predictions. The orange blobs show the teens’ heightened neural activity when they made abstract statements.

And: those blobs clearly overlap with well-established regions associated with the Default Mode Network.

The study includes a second (even more intricate!) picture of the executive control network — and its functional overlap with concrete statements.

The headline: we can see a (likely) brain basis for concrete and abstract thought in teens.

Equally important, a separate element of the study looks at the role of emotion in adolescent cognition. (One of the study’s authors, Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, has worked on this topic for years.)

In brief, emotions don’t necessarily limit thinking. They can focus and motivate thinking:

“Rather than interfering with complex cognition, emotion in the context of abstract thinking may drive adolescents’ thinking forward.”

The much-discussed emotionality of teenage years might not be a bug, but a feature.

A Final Note

I’m especially happy to share this research because its lead author — Dr. Rebecca Gotlieb — has long been the book reviewer for this blog.

If you’ve ever wondered how she knows so much about the books she reviews, well, now you know.

Because of work that she (and so many other) researchers are doing, Dr. Fischer could now say that we’re entering 2nd grade in our understanding of the brain…

A Final Final Note

Neuroscience studies always include more details than can be clearly summarized in a blog post. For those of you who REALLY want to dig into the specifics, I’ll add three more interesting points.

First: knowing that scientific research focuses too much on one narrow social stratum, the researchers made a point to work with students who aren’t typically included in such studies.

In this case, they worked with students with a lower “socio-economic status” (SES), as measured by — among other things — whether or not they received free- or reduced-priced lunch. Researchers often overlook low SES students, so it’s exciting this team made a point to widen their horizons.

Second: researchers found that IQ didn’t matter to their results. In other words, “abstract social reasoning” isn’t measured by IQ — which might therefore be less important than some claim it to be.

Third: teachers typically think of “executive function” as a good thing. In this study, LOWER activity in the executive control network ended up helping abstract social thought.

Exactly what to make of this result — and how to use it in the classroom — is far from clear. But it underlines the dangers of oversimplification of such studies. Executive functions are good — obviously! But they’re not always beneficial for everything.

Rebecca Gotlieb, Xiao-Fei Yang, Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, Default and executive networks’ roles in diverse adolescents’ emotionally engaged construals of complex social issues, Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2021;, nsab108, https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsab108