A few years ago, a former student named Jeremy invited me out for coffee. (I haven’t changed his name, because I can’t think of any reason to do so.)

We were reminiscing about the good old days–in particular, the very fun group of students in the sophomore class with him.

At one point he said: “You know what I remember most vividly about your class?”

I waited.

“Instead of using a spoon, you’d wrap your teabag string around your pen to wring it out into the mug. That always AMAZED me.”

In my early days as a teacher, I would have been horrified by this comment.

We had done such good work in this class! We analyzed the heck out of Macbeth. Jeremy had become a splendid writer–he could subordinate a quotation in an appositive like a pro. We had inspiring conversations about Their Eyes Were Watching God.

And all he remembered was the way I wrung out a tea bag?

The Hidden Compliment

Jeremy’s comment might seem like terrible news, but I think it’s good news. Here’s why:

The goal of sophomore English is for Jeremy to learn particular skills, facts, and habits of mind.

That is: he should remember–say–how to write a topic sentence with parallel abstract nouns.

However, he need not remember the specific tasks he undertook to learn that skill.

For example, when he wrote his essay about Grapes of Wrath, he got better at writing essays. Whether or not he remembers the argument he made in that paper, he honed his analytical habits and writing skills. (How do I know? His next paper was better. And the next.)

He doesn’t remember the day he learned how to do those things. But, he definitely learned how to do them.

Many Memories

When psychologists first began studying memory, they quickly realized that “memory” isn’t one thing. We’ve got lots of different kinds of memory.

Those distinct memory systems remember different kinds of things. They store those memories in different places.

For instance: I’ve written a lot about working memory. That essential cognitive system works in a very particular way, with very important strengths and limitations.

But, say procedural memory works very differently. Procedural memory helps us remember how to do things: like, say, ride a bike, or form the past tense of an irregular verb.

These distinctions help me understand Jeremy’s memories of my class.

Jeremy had a strong autobiographical memory: my wringing out a teabag with my pen.

As the name suggests, autobiographical memories are rich with details about the events and people and circumstances.

You have countless such memories:

The time you poured coffee on your boss’s desk;

The first time you met your current partner;

The time you forgot your lines on stage.

You can call up vivid specifics with delicious–or agonizing–precision.

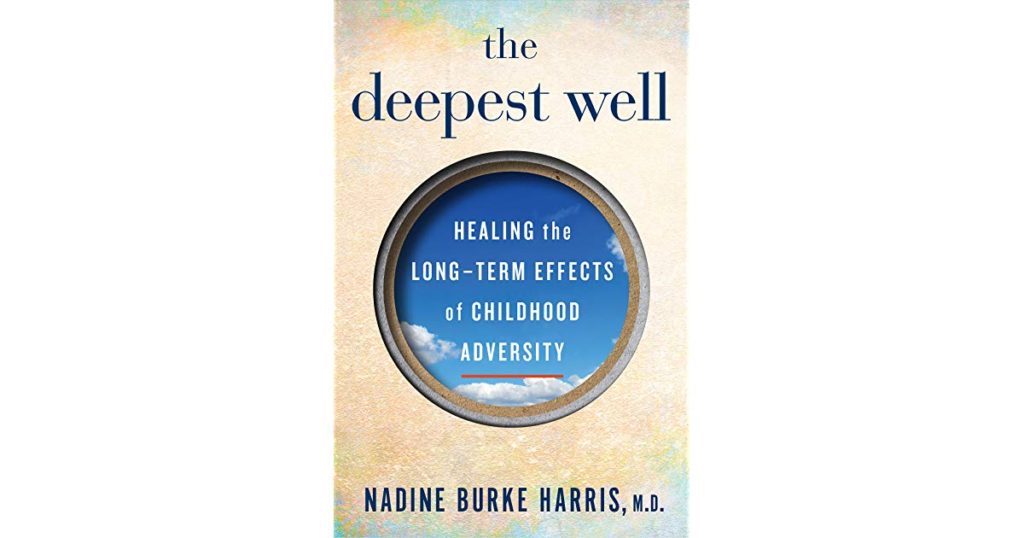

At the same time, Jeremy has lots of semantic memories from our class. As Clare Sealy describes them, semantic memories are “context free.” They “have been liberated from the emotional and spatiotemporal context in which they were first acquired.”

For instance:

Jeremy knows the difference between a direct object and a subject complement.

Having read The Ballad of the Sad Cafe, he knows how to analyze love triangles in literature.

Knowing how we define the word “romance” in English, he can explain the (many) bizarrenesses of The Scarlet Letter.

However, those semantic memories have an entirely feel from autobiographical memories. They lack the vivid specifics.

Jeremy knows that a subject complement “renames or describes” the subject. But he can’t tell you the tie I was wearing when I first explained that. He can’t tell you the (probably gruesome) example I used to make the distinction clear.

If he could, they would be autobiographical memories as well as semantic memories.

Why The Distinction Matters

As teachers, we’re tempted–often encouraged–to make our classes dramatically memorable. We want our students to remember the time that we…

Surprisingly, that approach has a hidden downside.

As Clare Sealy explains in a recent essay, we can easily use information in semantic memory in a variety of circumstances. That is: transfer is relatively easy with semantic memory.

However, that’s not true for autobiographical memory. Because autobiographical memory is bound up with the vivid specifics of that very moment on that very day (in that very room with those very people), students can struggle to shift the underlying insight to new circumstances.

In other words: the vivid freshness of autobiographical memory impedes transfer.

Sealy explains this so nimbly that I want to quote her at length:

Emotional and sensory cues are triggered when we try to retrieve an autobiographical memory. The problem is that sometime they remember the contextual tags but not the actual learning.

Autobiographical memory is so tied up with context, it is no good for remembering things once that context is no longer present.

This means that it has serious limitations in terms of its usefulness as the main strategy for educating children, since whatever is remembered is so bound up with the context in which it was taught. This does not make for flexible, transferable learning that can be brought to bear in different contexts and circumstances.

By the way, in the preceding passage, I’ve used the phrase “autobiographical memory” when Sealy wrote “episodic memory.” The two terms mean the same thing; I think that “autobiographical memory” is a more intuitive label.

To Sum Up

Of course we want our students to remember us and our class: the fun events, the dramatic personalities, the meaningful milestones.

And, we also want them to remember the topics and ideas and processes they learned.

Crucially, the word “remember” means something different in those two sentences; the first is autobiographical memory, the second is semantic.

Teaching strategies that emphasize remembering events might (sadly) make it harder to remember ideas and processes.

So, we should use teaching strategies that foster the creation of semantic memories.

Happily, the autobiographical memories will take care of themselves.

Clare Sealy’s essay appears in The researchED Guide to Education Myths: An Evidence-Informed Guide for Teachers. The (ironic) title is ” Memorable Experiences Are the Best Way to Help Children Remember Things.”