When our students learn, we naturally want them to show us what they’ve learned.

Most schools rely, in varying degrees, on tests. The logic seems simple: if students know something, they can demonstrate their knowledge on this quiz, or test, or exam.

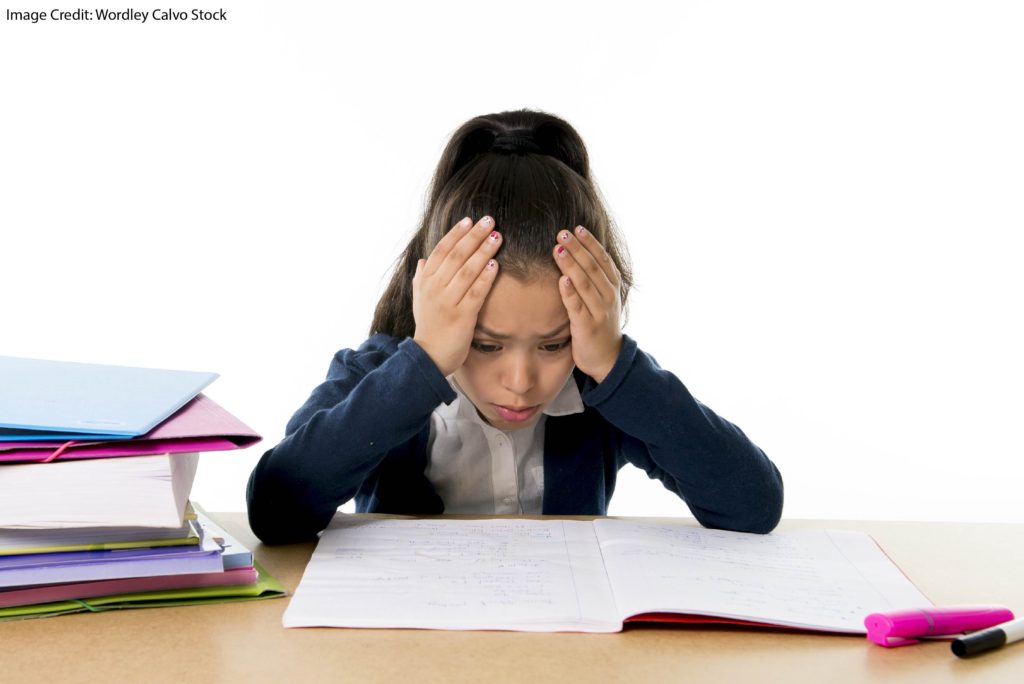

But, what about students who feel test anxiety?

These students might learn the material, but not be able to show what they’ve learned — at least, not as well.

The idea of test anxiety has been around for decades, and a significant pool of research suggests it correlates with measurably lower test grades.

How do we fix the problem?

Step 1: Defining the Problem

As always, we can’t really fix a problem until we understand the problem.

When we consider test anxiety, the explanation seems entirely straightforward.

Most students feel some degree of stress during tests. That’s normal, and can be helpful.

Some students, however, feel unhelpfully high levels of stress during tests. Distracted by sweaty palms and intrusive thoughts, they don’t concentrate on the cognitive task at hand.

In short: test anxiety harms the student during the test. Teachers can help students by reducing their stress in the moment. (Yes, we have lots of strategies to do so — see below.)

But wait!

What it that theory isn’t true? What if test anxiety muddles cognitive performance at some other time? If that’s true, then our “in-the-moment” strategies won’t help — or, won’t help enough.

Intriguing Hypothesis

How would we test this unsettling question?

A group of researchers in Germany discovered a thoughtful strategy.

Medical students in Germany spend lots of time (like, say, months) preparing for a high-stakes final exam.

Dr. Maria Theobald worked with over 300 of these students, who used an online learning platform to study. On this platform, these students…

… practiced problems from previous exams, and

… took five practice tests.

She also measured their test anxiety in two ways.

First, she measured their overall test anxiety, with a standard questionnaire.

Second, she measured their day-to-day test anxiety, rating their “tension about the upcoming study day” on a 1-5 scale.

And, of course, she measured lots of other things. (Spoiler alert: Theobald measured students’ working memory — a detail that will be important later.)

What happens when these researchers put all these pieces together?

Surprising Results

Here are the headlines:

Test anxiety does not harm students’ exam performance in the moment.

Instead, it does harm their performance during the preparation for the exam.

Why does Theobald reach this conclusion?

If test anxiety harms students in the moment, then these students should do worse on the FINAL TEST than they did on the PRACTICE PROBLEMS and the PRACTICE TESTS.

Imagine that a student averaged an 85 on practice problems and an 84 on practice tests, but score a 75 on the final test. We would say:

“Something strange happened.

It looks like anxiety prevented students from demonstrating the knowledge they obviously have. (They obviously have it because they scored so well on the practice problems/tests).”

Theobald’s data, however, did not fit that pattern at all.

Instead, anxious students made less progress during the months of study BEFORE the test. And, their final test score was right in line with that earlier (lower) performance.

That is: anxious students scored 75 on the practice problems and practice tests … and then a 75 on the final exam as well. (These numbers are examples, not real data.)

So, we find ourselves saying:

“Hmm. These anxious students scored consistently lower than their peers — both on the final test and on the months of practice work they did.

Their anxiety didn’t lower their final score in the moment. It interfered with their learning trajectory as they prepared for the final test.”

Reader: I did not expect these results.

What Should Teachers Do?

First, we should — in my view — continue with stress reduction strategies in the moment.

We’ve got evidence that letting students vent their stress improves exam performance. And we’ve got evidence that helping students reframe stress as positive (“I’m excited!”) helps as well.

So, I wouldn’t give up on these pre-test strategies just yet.

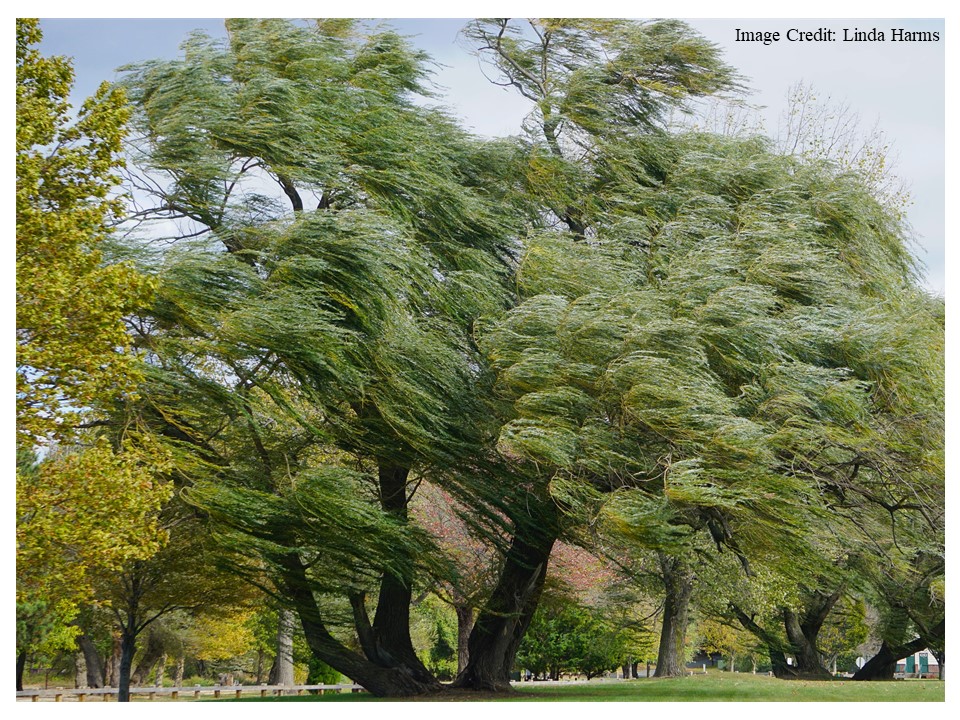

Second, this research encourages us to take the long view. “In the moment” strategies might help some, but longer-term strategies now sound more urgent.

Because Theobald’s research is so new, I haven’t seen any responses to it — much less research based suggestions.

But I think of “values affirmation” as one potential (let me repeat: “potential”) way to reduce this kind of test anxiety.

I’ll be keeping my eye out for others. If you hear of a promising one, I hope you’ll let me know.

Potential Limitations

First: an important limitation.

All research studies include limitations, so it’s no criticism to say this study does too.

Specifically, this research was done with students completing medical school. That is: they (probably) have been highly academically successful for decades. They (probably) bring higher levels of motivation than many students.

And, their test-anxiety profile might not match those of my students, or of yours.

Until these findings are replicated in other students populations (and cultural contexts), I would rely on professional experience to adapt them to our own settings.

Second: an important non-limitation.

I noted above that Theobald measured students’ working memory. (Long-time readers know: I’m obsessed with working memory.)

This research team speculated — plausibly — that working memory capacity might mitigate the effects of test anxiety.

That is: students with more cognitive space to think might feel less distracted by anxious thoughts.

However, their data did not support that hypothesis. Students with high working memory are just as troubled by test anxiety as those with lower working memory.

TL;DR

In this study with German medical students, test anxiety interferes NOT with student performance on the final test, but with their learning before the test.

If further studies support this conclusion, we should refocus our work on helping those students during the weeks and months before the test itself.

Theobald, M., Breitwieser, J., & Brod, G. (2022). Test Anxiety Does Not Predict Exam Performance When Knowledge Is Controlled For: Strong Evidence Against the Interference Hypothesis of Test Anxiety. Psychological Science, 09567976221119391.

![An Exciting Event In Mindfulness Research [Repost]](https://www.learningandthebrain.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/AdobeStock_89371077_Credit-1024x683.jpg)