I was invited to speak at March 4 Science SIGNS Summit on Saturday. The question was: what challenges bedevil the field of Science Communication? And, what can we do to fix them?

Here is, more or less, the first half of what I said:

I began my professional life as a high school English teacher, and loved that work for several centuries.

For teachers, the challenge of science communication is NOT that many (many) teachers are deeply skeptical of outside experts telling us how to be better teachers.

The problem is that many (many) teachers are RIGHTLY deeply skeptical of outside experts telling us how to be better teachers.

I don’t know how it works in other professions. But, oddly, people who have never taught anyone anything feel comfortable telling teachers how to do our jobs better. At any party you attend, someone will blithely tell you to do this one simple thing, and your job will get every so much easier.

Do people tell surgeons which scalpel to use? Do people tell fire-fighters to be more like fire-fighters in Finland, where they’re so much better at fighting fires?

Just Do It

Here’s a true story. (I’m blurring the details, for obvious reasons.)

I once attended a conference (not, by the way, a Learning and the Brain conference) where the keynote speaker presented data on a specific teaching approach. The first question, quite marvelously, went like this:

Now that you’ve shared your ideas and your data with us, what plans do you have to hear back from teachers who try this idea? How can we keep this dialogue going, so you can learn from teachers as they learn from you?

The speaker thought for a moment and said: “We have no such plans. We’ve done the research. We know the right answer. Teachers should just do it. Do it.”

For this speaker, “interdisciplinary” apparently means “I tell you what to do, and you do it.”

“Too Much Skepticism”

For those of us in the field of Science Communication, teachers may seem unreasonably resistant — unreasonably skeptical — of outside experts. We exhibit too much skepticism.

But I suspect most people don’t much like outside experts.

If we, as science communicators, want people to hear and believe what we say, we should practice becoming inside experts.

For example: imagine that I change my focus, and strive to improve education through the legislature. I want to persuade congress to revoke old laws and pass new ones.

My temptation, of course, would be to talk with representatives and senators about brain science. Here’s the psychology. Here’s the neuroscience. Legislators should pass laws that align with that research.

However, I suspect that such guidance would be much more effective if I knew in a gritty, day-to-day way what legislators really do.

To find this out, I should — perhaps — volunteer at a representative’s campaign, or intern at my senator’s office. I should attend committee meetings and community meetings. I might even (perish the thought) try my hand at political fundraising.

A New Language, or Two

One the one hand, none of these activities (the volunteering, the interning, the fundraising) has much to do with brain science.

On the other hand, all of them will help me learn to speak politics. And, if I can speak politics, I’ll be vastly more effective framing science research to persuade legislators to act.

I won’t be an outside expert. I will sound increasingly like an inside expert.

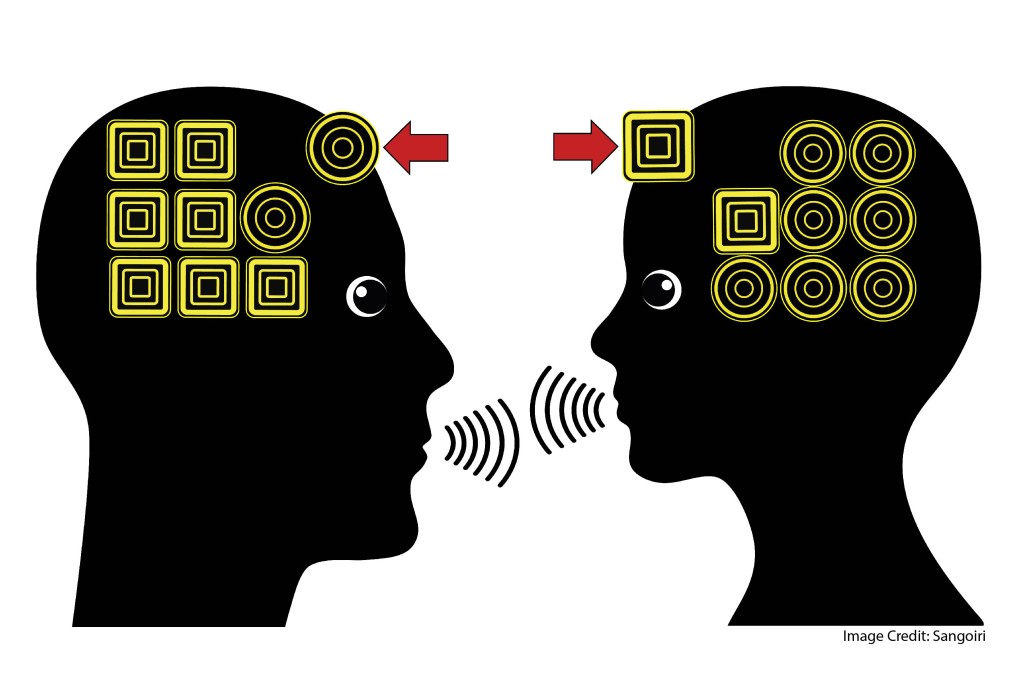

By implication, I’m encouraging two kinds of cross-training.

Psychology and neuroscience researchers can make their guidance more meaningful and useful by spending more time — real time — working with the classroom teachers they seek to guide.

And: classroom teachers can collaborate with researchers as equals if and only if we devote more time — real time — to mastering the complex disciplines that we hope will benefit our students.

This is a big ask. I’m not talking about days or weeks, but months and years.

I wish we had an easier way to accomplish this mission. And yet, for science communication to succeed — for brain researchers and teachers to work effectively together — we really do need this kind of sustained, gritty, determined exploration.

I’m thinking our students are worth it.

In Part II, I’ll consider the dangers of too LITTLE skepticism.

![Just Not a Useful Debate: Learning Styles Theory [Updated]](https://www.learningandthebrain.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/AdobeStock_49195554_Credit-1024x683.jpg)