I spend A LOT of time on this blog debunking “research-based” certainties.

No, handwriting isn’t obviously better than laptops for taking notes.

No, the “jigsaw method” isn’t a certain winner.

No, “the ten minute rule” isn’t a rule, and doesn’t last ten minutes.

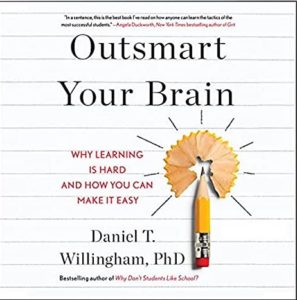

No, dopytocin isn’t worth your attention. (Ok, I made up the word “dopytocin.” The blog post explains why.)

And so forth.

For that reason, I was DELIGHTED to discover a strong “research-based” claim that might hold up to scrutiny. Here’s the story…

The Quest Begins…

A colleague posted on eXTwitter a simple question; it went something like this:

I’ve always heard that “blue light from screens before bed” interferes with sleep — in fact, I’ve heard “science says so.” But: I just realized that I don’t actually know anything about the science. Now I’m wondering if it’s true…

Well, NOW YOU’VE GOT MY ATTENTION.

I too have frequently heard the “blue light before bed” claim. I too had understood that “research says so.” I too had never explored that research. It’s obviously time to saddle up.

I confess I did so with a small sense of dismay.

By nature, I’m not a contrarian. I don’t want to go around saying “that thing that everyone believes is ‘based on science’ has no good research support that I can find.” I’m not trying to lose friends and upset people.

But, as you can see from the list above, LOTS of people say “you should do X because research proves Y” — even though research REALLY does not consistently support Y. (Did I mention the “ten minute rule”?)

Fearing that I would — once again — find myself contradicting commonly held wisdom, I dove in.

As is so often the case, I started at elicit.org. (Important note: NOT illicit.org. I have no idea what’s at illicit.org…but the idea makes me nervous. This is a G-rated blog!)

I put this question into its search box: “Does blue light from screens interfere with sleep?”

And I held my breath…

Treasure Unveiled

Come to find out: elicit.org has strong opinions!

Blue light from screens has been shown to interfere with sleep in several ways. It can shorten and worsen sleep quality, delay the onset of sleep, and increase feelings of fatigue (Kurek 2023). However, using amber filters on smartphone screens can improve sleep quality by blocking the short-wavelength blue light (Mortazavi 2018).

Wearing color-tinted lenses to filter short-wavelength light exposure before sleep may also improve sleep, particularly in individuals with certain conditions (Shechter 2020). Exposure to blue-enriched light at low room light levels can impact homeostatic sleep regulation, reducing frontal slow wave activity during the first non-rapid eye movement episode (Chellappa 2013).

I like Elicit because it provides an ENORMOUS amount of data. I won’t attempt to list or summarize all the studies it highlighted. But I’ll point to a few factors that made this claim especially compelling.

Boundary conditions: studies have found this claim to be true across a variety of age groups. This conclusion doesn’t apply simply to a niche-y cohort (say, people in Atlanta who own bison farms); it applies wherever we look.

Positive and negative findings: studies show both that more blue light interferes with sleep and that blocking blue light improves sleep.

Recency: these studies all come from the last decade. In other words: Elicit didn’t pull them up from the late ’80s. We’re talking about the most recent findings here.

I could go on.

Don’t Stop Now

I believe it was Adam Grant who wrote:

Be the kind of person who wants to hear what s/he doesn’t want to hear.

That is: when I start to believe a particular “research-based” claim, I should look hard for contradictory evidence.

If the evidence in favor outweighs the evidence against — and only if the evidence in favor outweighs the evidence against — can I start to believe the claim.

So, I started looking for contradictory evidence.

Here’s an easy strategy: google the claim with the word “controversy.” As in:

“Blue light interferes with sleep controversy”

or

“blue light interferes with sleep myth”

If such a controvery exists, then that google search should find it.

Sure enough, those two searches started to raise some interesting doubts.

I found two articles in the popular press — one in Time magazine, the other in Salon — pointing to this recent study. In it, researchers studied mice and found that yellow light — not blue light — seems the likelier candidate to be interfering with sleep.

Honestly, I found the technical language almost impenetrable, but I think the argument is: yellow light looks more like daylight, and blue light looks more like twilight. So: yellow light (but not blue light) is likelier to interfere with the various chemical processes that point the brain toward sleep. And: that’s what they found with the mice.

Of course, studies in mice are intersting but are never conclusive. (One of my research mottos: “Never, never, never change your teaching practice based on research into non-human animals.”)

So, what happens when we test the yellow-light/blue-light hypothesis in humans?

So Glad You Asked…

Inspired by that mouse study, another researched checked out the hypothesis in humans. She measured the effects of evening exposure to light along various wavelengths — yellow, yellow/blue, blue — and found…

…nada.

As in, no wavelength combo had a different effect than any other.

However — this is an important “however” — the study included exactly 16 people. So, these results deserve notice, but don’t overturn all those other studies about the dangers of blue-light.

After all this back-n-forth, where do all these research findings leave us?

First: we do indeed have LOTS of research suggesting that blue light interferes with sleep.

Second: that research has been questioned recently and plausibly. But, those plausible questions don’t (yet) have lots of mojo. Mice + 16 people don’t add up to a fully persuasive case.

By this point, I’ve spent about three hours noodling this question about, and I’m coming around to this point of view:

Maybe the problem isn’t the blue light; maybe it’s the BRIGHT light. Yellow, blue, pink, whatever.

So, rather than buy special glasses or install light filters, I should put down my iPad and read from paper once I get in bed.

I should say that this conclusion isn’t exactly “research based.” Instead, it’s a way of accepting a muddle in the scientific results, and trying to find a good way forward.

This approach guides me in my classroom work, and now it will guide me when it comes to my Kindle as well.

![The Unexpected Problem with Learning Styles Theory [Reposted]](https://www.learningandthebrain.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Learning-Styles-Vector.jpg)

![Why Do “Learning Styles” Theories Persist? [Updated 6-7-19]](https://www.learningandthebrain.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/AdobeStock_80919293_Credit-1024x609.jpg)