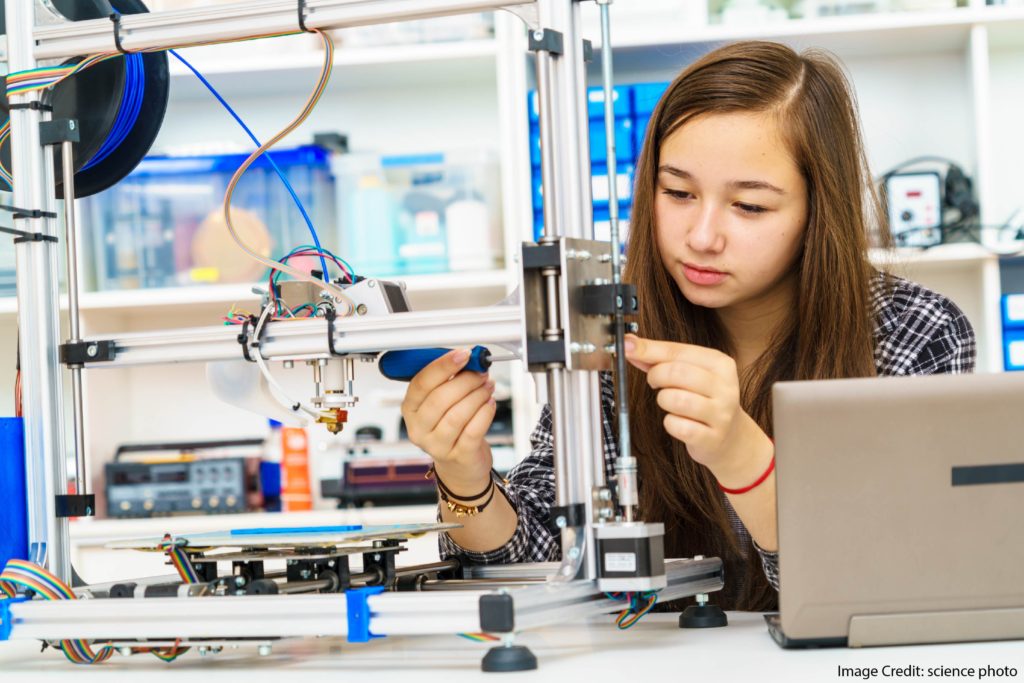

Classrooms should do more than simply house our students. We want them to welcome students. To set an encouraging and academic tone. To reflect the values our schools champion.

That’s a lot of work for one classroom to do.

As a result, our rooms sometimes end up looking like the nearby image: a busy tumult of color and stuff.

Does this level of decoration have the desired result? Does it make students feel welcome, valued, and academic? Realistically, might it also distract them?

Two researchers in Portugal wanted to find out.

Today’s Research

Several people have studied the effect of classroom decoration on learning. (In perhaps the best-know study, Fisher, Godwin and Seltman showed that kindergarteners learned less in a highly decorated classroom.)

Rodrigues and Pandeirada wanted to know exactly which mental functions were disrupted by all that decoration. Their study design couldn’t be simpler.

These researchers created two study environments.

The first looks basically like a library carrel with a dull white finish.

The second added lots of lively, upbeat photos to that carrel.

The result isn’t as garish as the photo above, but it’s certainly quite busy. (You can see photographs of these two environments on page 9 if you click the link above.)

Rodrigues and Pandeirada then had 8-12 year-olds try tests of visual attention and memory.

For instance: students had to tap blocks in a certain order. (Like the game Simon from when I was a kid.) Or, they had to recreate a complex drawing.

Crucially, these 8-12 year-olds did these tasks in both environments. Researchers wanted to know: did the visual environment make a difference in their performance?

It certainly did. On all four tests — both visual attention and memory — students did worse.

In short: when the visual environment is too busy, thinking gets harder. (By the way, visual distraction is not a “desirable difficulty.” It results in less learning.)

Two Sensible Questions

When I discuss this kind of research with teachers, they often have two very reasonable questions.

Question #1: how much is “too much”? More specifically, is my classroom “too much”?

Here’s my suggestion. Invite a non-teacher friend into your classroom. Don’t explain why. Notice their reaction.

If you get comments on the decoration — even polite comments — then it’s probably over-decorated.

“What a wonderfully colorful room!” sounds like a compliment. But, if your students see a “wonderfully colorful room” every day, they might be more distracted than energized.

Question #2: Won’t students get used to the busy decoration? My classroom might look over-decorated now, but once you’ve been here for a while, it will feel like home.

This question has not, as far as I know, been studied directly. But, the short answer is “probably not.”

The Fisher et al. study cited above lasted two weeks. Even with that much time to “get used to the decoration,” students still did worse in the highly-decorated classroom.

More broadly, Barrett et al. looked at data for 150+ classrooms in 27 schools. They arrived at several conclusions. The pertinent headline here is: moderate levels of decoration (“complexity”) resulted in the most learning.

In other words: students might get used to visual complexity. But: the research in the field isn’t (as far as I know) giving us reason to think so.

Summer Thoughts

Here’s the key take-away from Rodrigues and Pandeirada’s research: we should take some time this summer to think realistically about our classroom’s decoration.

We want our spaces to be welcoming and informative. And, we want them to promote — not distract from — learning.

Research can point us in the right direction. We teachers will figure out how best to apply that research to our classrooms, for our students.

A final note: I’ve chatted by email with the study’s authors. They are, appropriately, hesitant to extrapolate too much from their library-carrel to real classrooms.

They show, persuasively, that visual distractions can interfere with attention and memory. But: they didn’t measure what happens in a classroom with other students, and teachers, and so forth.

I think the conclusions above are reasonable applications of these research findings; but, they are my own, and not part of the study itself.

![[A Specific] Movement Helped [Specific] Students Learn [A Specific] Thing](https://www.learningandthebrain.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/AdobeStock_201115751_Credit-1024x684.jpg)