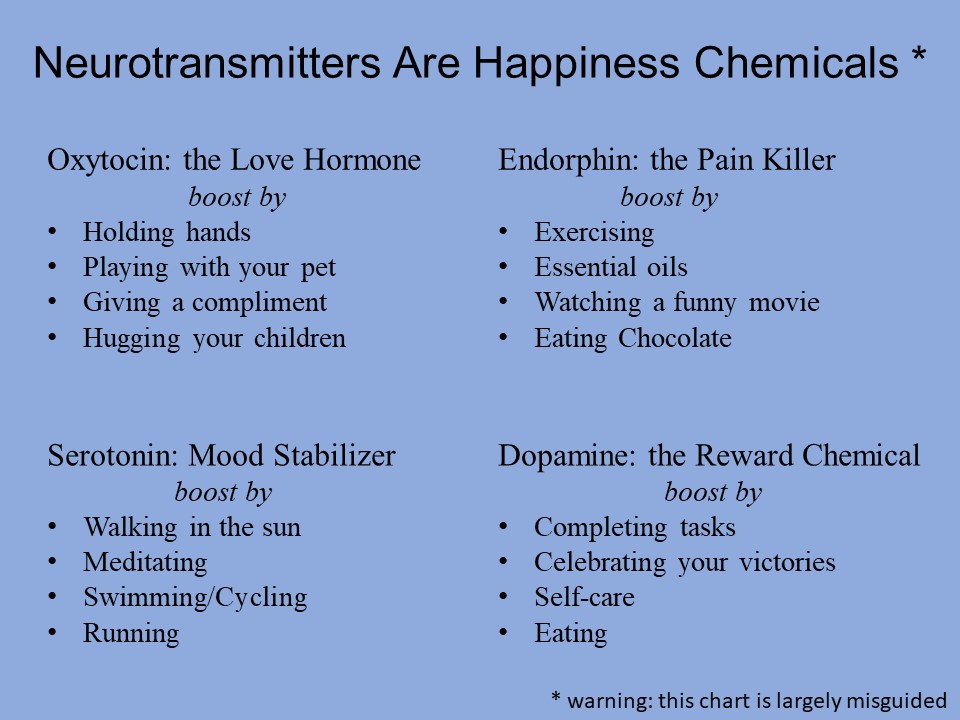

I recently ran across a version* of this chart:

As you can see, this chart lists several neurotransmitters and makes recommendations based on their purported roles.

If you want to feel love, you should increase oxytocin. To do so, play with your dog.

If you want to feel more stable, you should boost serotonin. To do so, meditate, or go for a run.

And so forth.

On the one hand, this chart seems harmless enough. It recommends that we do quite sensible things — who can argue against “self-care,” or “hugging your children”? — and so can hardly provoke much controversy.

I, however, see at least two reasons to warn against it.

Willingham’s Razor

Most everyone has read Dan Willingham’s Why Don’t Students Like School? (If you haven’t: RUN, don’t walk, to do so.)

Professor Willingham has also written a less well known book called When Can You Trust the Experts?, which offers lots of wise advice on seeing though bad “expert” advice.

One strategy he recommends:

Reread the “brain-based” teaching advice, and mentally subtract all the brainy words. If the advice makes good sense without them, why were they there in the first place? **

In the lists above, do we really need the names of the neurotransmitters for that advice to make sense?

To feel a sense of accomplishment, accomplish something.

If you want to feel better, eat chocolate.

To calm down, walk (or run) outdoors.

Who could object to these suggestions? Do we need multi-syllable words to embrace them?

I worry, in fact, that such charts create bad mental habits for teachers. Those habits sound like this:

If someone knows complicated neuro-terminology, then their teaching advice must be accurate. When a blogger uses the phrases “corpus callosum” and “research says,” therefore, I have to take their teaching advice.

No, you really DON’T have to take their advice. LOTS of people use the language of neuroscience to make their suggestions sounds more authoritative.

As I’ve written elsewhere, neuroscience rarely produces classroom-ready teaching advice.

PSYCHOLOGY gives teachers great ideas about memory and attention and learning and motivation.

A biological understanding of what’s happening during those mental functions (i.e., neuroscience) is fascinating, but doesn’t tell teachers what to do.

In brief: beware people who use neuro-lingo to advise you on practical, day-to-day stuff. Like, say, that chart about “happiness chemicals.”

When Simplification Leads to Oversimplification

My first concern: the chart misleadingly implies that neuroscientific terminology makes advice better.

My second concern: the chart wildly oversimplifies fantastically complicated brain realities.

For instance, this chart — like everything else on the interwebs — calls oxytocin “the love hormone.”

However, that moniker doesn’t remotely capture its complexity. As best I understand it (and my understanding is very tentative), oxytocin makes social interactions more intense — in both positive AND NEGATIVE directions.

So: when we add oxytocin, love burns brighter, hatred smoulders hotter, jealously rages more greenly.

To call it the “love hormone” is like saying “the weather is good.” Well, the weather can be good — but there are SO MANY OTHER OPTIONS.

The statement isn’t exactly wrong. But its limited representation of the truth makes it a particular kind of wrong.

So too the idea that dopamine is a “reward chemical.” Like oxytocin’s function, dopamine’s function includes such intricate nuance as to be difficult to describe in paragraphs — much less a handy catchphrase. ***

By the way: the most comprehensive and useful description of neurotransmitters I know comes in Robert Sapolsky’s book Behave. As you’ll see, they’re REALLY complicated. (You can meet professor Sapolsky at our conference in February.)

TL;DR

Yes, walking outside and hugging children and exercising are all good ideas for mental health.

No, we don’t need the names of neurotransmitters to make that advice persuasive.

We might worry about taking advice from people who imply that neuro-lingo does make it more persuasive.

And we can be confident that neurotransmitters are much, MUCH more complicated than such simplistic advice implies.

* I’ve made my own modified version of this chart. The point of this blog post is not to criticize the individuals who created the original, but to warn against the kind of thinking that produced it. “Name and shame” isn’t how we roll.

** I’m paraphrasing from memory. I’m on vacation, and the book is snug at home.

*** [Update on 12/30/22] I’ve just come across this study, which explores some of the contradictions and nuances in the function of serotonin as well.

About Andrew Watson

About Andrew Watson