Many years ago, I accepted a new school role overseeing curriculum, instruction, and faculty. I started this job with lots of enthusiasm and — I thought — several good ideas. I believed in collaborative leadership, and worked hard to welcome my colleagues into the admin team’s decisions.

In brief, the experience was a bust. All my enthusiasm and good ideas and collaborative approach…well, they didn’t accomplish very much.

Perhaps as a result, I’ve spent the last several years focusing not on collective school systems, but on individuals within systems. While I certainly hope that school leaders and district administrators read this blog and take action upon these ideas, I’m mostly focusing on YOU: individual readers who can make wise decisions about your own craft and classroom.

And yet, occasionally I do wonder what would have happened if I’d been more skilled at managing school-wide change…

What I Wish I’d Known

Given this background, you understand why I was so curious to read Change Starts Here by Shane Leaning and Efraim Lerner. These authors have years of experience working in and with schools. And: they’re experts at helping schools as a whole — not just individuals within the school — make meaningful changes.

Let me highlight three of the book’s many strengths.

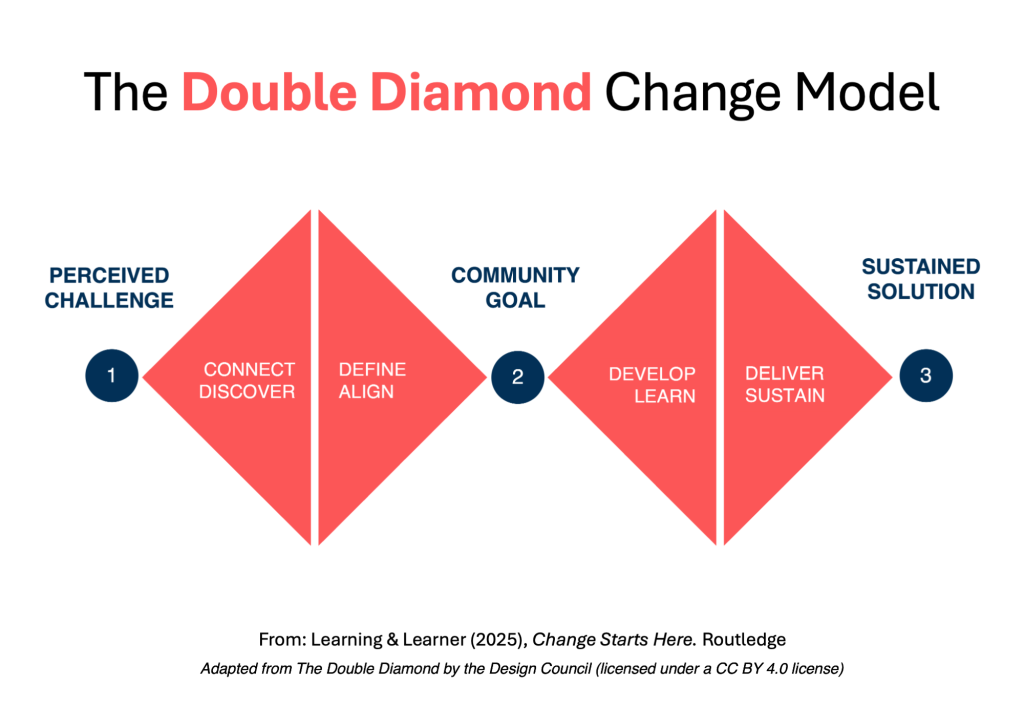

First: Leaning and Lerner begin with a clear but powerful model — a model showing the process by which a PERCEIVED CHALLENGE becomes a COMMUNITY GOAL, and then a SUSTAINED SOLUTION. By explicitly building both divergent and convergent thinking into their model — those expanding and contracting triangles — L&L steer wisely past many of the traps that I fell into in my own leadership role.

Second: Change Starts Here echoes my own thinking about the importance of context:

We are not here to tell you to follow our model in every detail with fidelity. We’re not even here to tell you to follow the model at all. Instead, we provide a model that acts as a framework to ask yourself…powerful questions.

Regular readers know my mantra: “don’t do this thing; instead, think this way.” From my perspective, cognitive science research can’t tell teachers what to do. Instead, it can offer us a wise and fresh perspective on how to think better about what we do.

Clearly, L&L see their work the same way. No one process serves all schools equally well. They’ve got latitude and flexibility built into their model.

Third: Let’s talk about those “powerful questions”…

Powerful Questions

Leaning and Lerner offer forty — yes, 40! — questions to guide you through their model.

Let’s pick a few of these at random:

- Question #26: “On a scale of 1-10, how much do we know? How can we +1?”

Like so many of their questions, this one sounds obvious once stated out loud. And yet, I can easily recall many leadership meetings where we assumed — without really thinking about it — that we already knew everything that we needed to know. If we had asked ourselves this question, I think we would have realized important knowledge gaps and invited more people into the conversation.

(After a security incident at one school where I worked, the admin team held a meeting to review security protocols. They neglected to invite the teacher who had created those protocols…)

- Question #11: “How will this challenge make us better?”

In my own leadership tenure, I (mostly) felt comfortable taking on challenges. I don’t love conflict, but I’m willing to walk into it to help develop a healthy solution.

Question #11, however, gives me a fresh perspective on that “willingness.” I didn’t particularly see challenges as a chance to get better; I saw them as an unpleasantness that needed getting through. Leaning and Lerner’s reframe would have been a useful reminder about that leaderly perspective.

- Question #20: “How will we celebrate?”

The various strategic planning processes that I participated in more-or-less got the job done. But they never felt celebration-worthy. They felt, instead, like a thorough drubbing that we had all survived.

Looking back on our work, I do think we accomplished goals worth celebrating. But I’m not sure that we gave ourselves the victory lap that we all — the whole school! — deserved.

By the way: I chose these three questions to show the range of Leaning and Lerner’s interests. From practical (#26) to tough-minded (#11) to aspirational (#20), they consider the process of change from every logistical and emotional position.

Beyond Recipes

I do suspect that some readers will say: “These ideas sound FANTASTIC! But, what specifically does this process look like in my school?”

On the one hand, this response makes sense. Given such an encouraging framework, we want to see it in action.

On the other hand, a book like this can’t really answer that question. Remember Leaning and Lerner’s guiding principle:

We are not here to tell you to follow our model in every detail with fidelity. We’re not even here to tell you to follow the model at all. Instead, we provide a model that acts as a framework to ask yourself…powerful questions.

These powerful questions would take my school along one path, while it would take your school along quite a different one. Such variety is a feature, not a bug. And, it means those of us who want change at scale have extra heavy lifting to do.

Leaning and Lerner have given school leaders what I wish I’d had 20 years ago: not a recipe to follow, but a framework for thinking clearly about change. If you’re ready to move beyond changing one classroom at a time — and willing to do the required heavy lifting — this book offers the questions you need to ask. And it guides those questions with lots of generous wisdom.

Leaning, S., & Lerner, E. (2025). Change Starts Here: What If Everything Your School Needed was Right in Front of You?. Taylor & Francis.