A colleague recently reached out to ask me about research into the benefits and perils of final exams in high school. Her question inspired a fun exploration of research on the topic; I thought it would be helpful to share both our conclusions and our process with you.

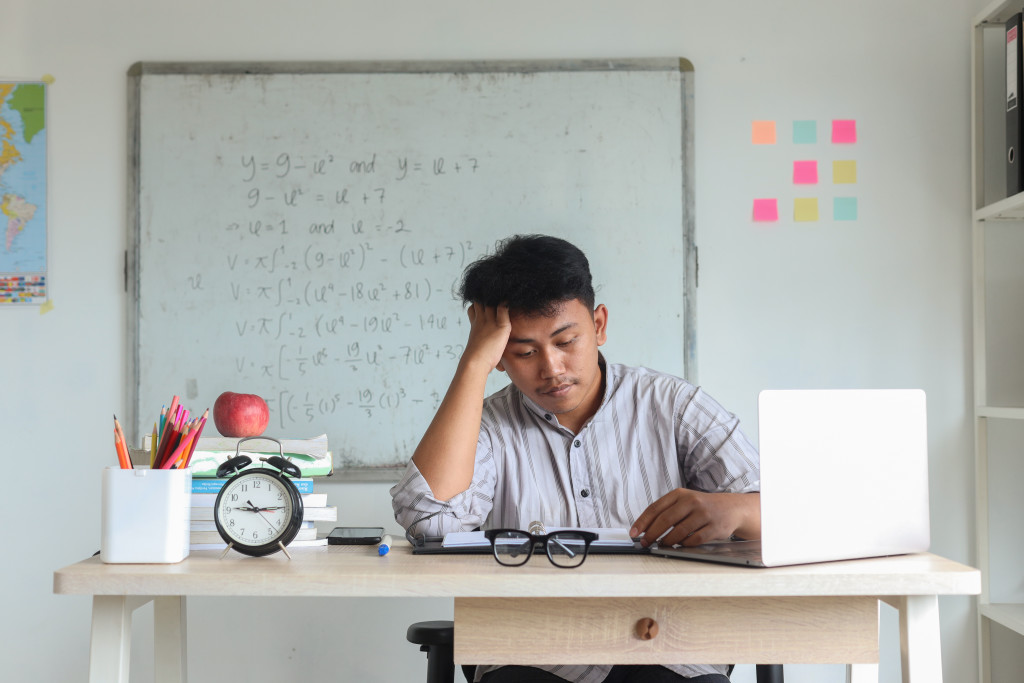

Before I dig into our discussion, it might be helpful to pause and ask yourself this question: “do I already have a firm opinion about final exams?”

That is: do you believe that exams provide much-needed accountability and a chance for meaningful accomplishment? Do you believe they subtract valuable instruction time and add needless academic stress? Your prior beliefs will shape the way you read the upcoming post, so you’ll probably learn more if you recognize your own preconceptions.

With this first step in place, let’s explore…

Not as Easy as it Looks

Our conversation started with a frank admission: it would be INCREDIBLY difficult to investigate this question directly.

To do so, we’d need to teach two identical courses – one of which does have a final exam, and the other of which does not.

This proposal, however, quickly becomes impossible.

Let’s say that one section of my English class has a cumulative final exam, and the other has a cumulative final project. The differences between an exam and a project require all sorts of other changes to the course…so the two experiences wouldn’t be similar enough to compare as apples and apples.

Almost any other attempt to answer questions about final exams directly leads to similar problems.

This realization might discourage those of us who regularly turn to research. At the same time, it forces us to rethink our question quite usefully.

Instead of asking:

“Are final exams good or bad?”

We can ask:

“When we think about a year-long learning experience, how can we conclude those months most helpfully? What set of cognitive experiences consolidates learning most effectively? And: how does the answer to that question depend on the specific context of my school?”

With that framework in mind, let’s get started…

Old Friends

Longtime readers know that I rely on several websites to launch my research journeys. In this case, my colleague and I started at elicit.org. I put in this question:

“Do final exams in high school benefit or harm learning?”

The results from this search highlight the complexity of the question.

This paper by Khanna et al argues that cumulative final exams benefit students more than non-cumulative exams; these benefits appear both in the short term – immediately after the exam – and up to 18 months later. (Technically speaking, 18 months is a LONG TIME.)

When I checked out that study on my two other go-to websites (connectedpapers.com, scite.ai), I found other papers that, roughly speaking, arrived at the same conclusion. Strikingly, those other papers suggested that cumulative exams especially benefit either struggling students, or students with less prior knowledge.

On the other hand, back at my elicit.org search, this study by Holme et al produces this bleak conclusion:

“High school exit exams have produced few expected benefits and been associated with costs for disadvantaged students.”

A quick search on connectedpapers.com finds that – sure enough – other researchers have reached roughly similar conclusions.

“Promising Principles”

As expected, our review of existing research shows the difficulty of answering this final-exam question directly.

So, let’s try a different strategy: returning to our reformulated question:

“When we think about a year-long learning experience, how can we conclude those months most helpfully? What set of cognitive experiences consolidates learning most effectively?”

Two Learning and the Brain stalwarts – David Daniel and John Almarode – often invite teachers to think about cognitive science not as rules to obey (“do this”), but as “promising principles” that guide our work (“think about this, then decide what to do”).

So: do we have any promising principles that might guide our question about final exams? Indeed we do!

This blog has written about spacing, interleaving, and retrieval practice so often that there’s no need to rehash those ideas in this post. And, it’s easy to see how to apply these promising principles to cumulative final exams. After all, such exams…

… almost REQUIRE spacing,

… almost REQUIRE interleaving,

… create MANY opportunities for retrieval practice.

Of course, almost anything can be done badly – and preparation for final exams is no exception. But – done well – final exams invite exactly the kind of desirable difficulty that cognitive science champions.

Slam Dunk?

Perhaps, then, we have answered my colleague’s question: schools should—no, schools MUST—use cumulative final exams to enact cognitive science principles.

…Insert sound of record scratch…

That statement overlooks the second part of the revised question above:

“What set of cognitive experiences consolidates learning most effectively? And: how does the answer to that question depend on the specific context of my school?”

In this case, my colleague works at a school that champions a progressive educational philosophy. In other words, final exams sound like a terrible idea.

Her school has long favored cumulative capstone projects. And even a cursory discussion makes it clear that such projects – like cumulative final exams – invite spacing, interleaving, and retrieval.

(Yes, yes: capstone projects can be designed very badly. So can final exams. Both can also be done well.)

As long as those capstone projects deliberately and thoughtfully enact all those promising desirably difficult principles, they too can consolidate a year’s worth of learning.

TL; DR

My collegial conversation suggests that cognitive science research neither forbids nor requires final exams.

Instead, that research gives us ways to think about the summary work that we do with students. We can adapt these promising principles to align with our own school philosophy. That conceptual combination – more than a specific research study – will guide us most wisely.

![Summer Plans: How Best to Use the Next Few Weeks [Repost]](https://www.learningandthebrain.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/AdobeStock_497101353-1024x688.jpeg)