Recently, I linked to a study suggesting potential downsides to bilingualism: in at least this one study, bilingual students were less successful with metacognition than monolingual students.

In that post, I noted that this one detriment doesn’t mean that bilinguals are “bad at thinking” in some broad way, or that bilingual education is necessarily a bad idea. Instead, that study was one interesting data point in a large and complex discussion.

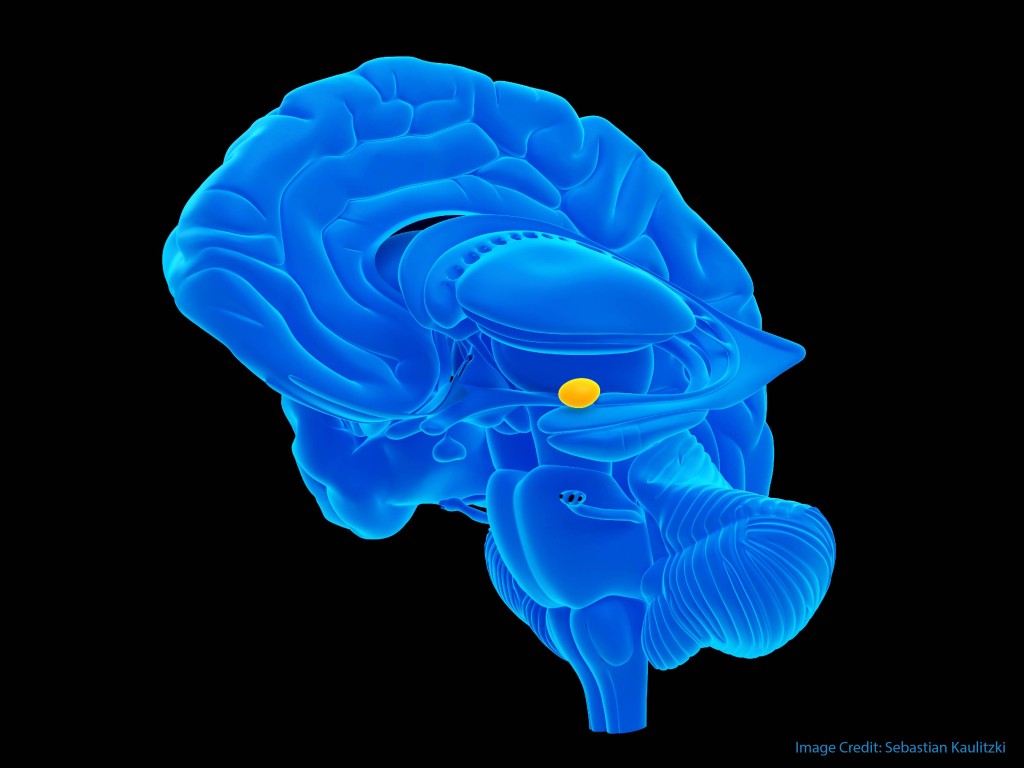

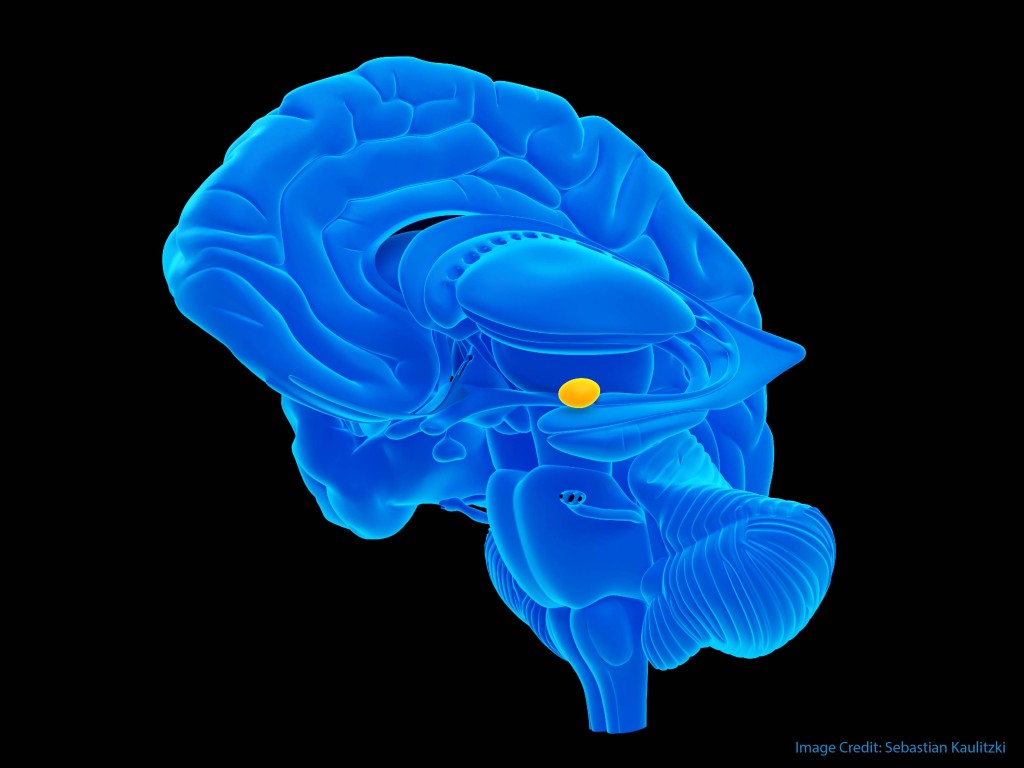

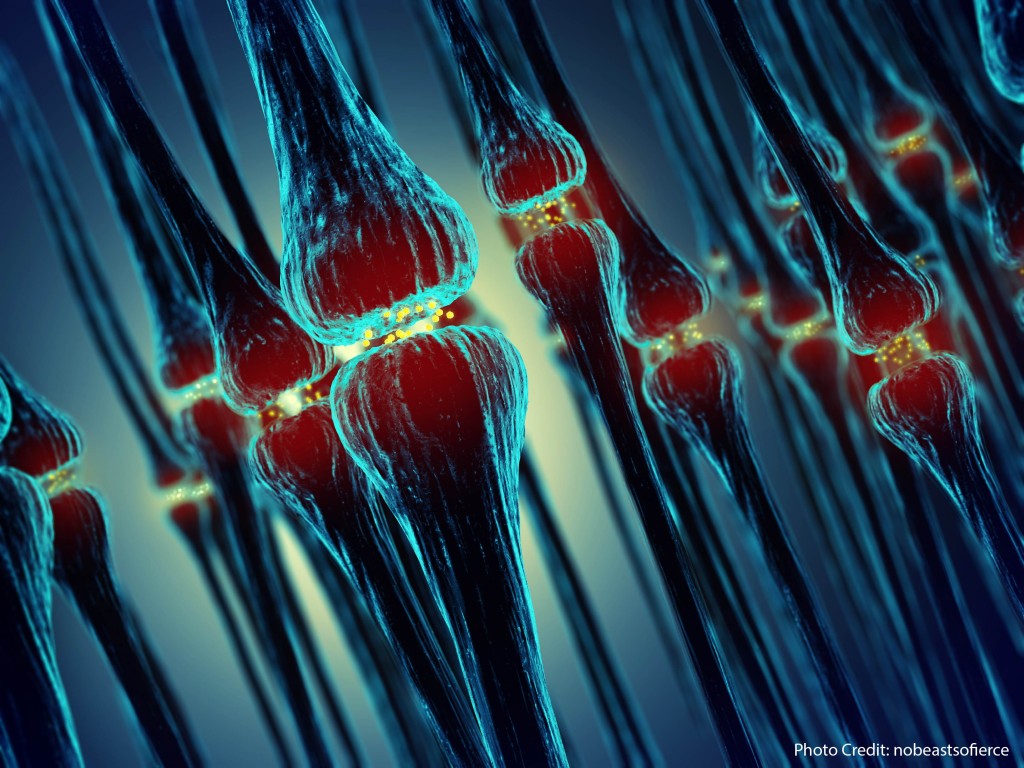

Well, that discussion has gotten even larger and more complex. A research team at the University of Montreal has explored the neural mechanisms that help adult bilinguals focus on some information without being distracted by other kinds of information.

Neuroscience is always complicated, but the simple version is this: bilinguals use more efficient networks to maintain focus on a particular information stream.

In other words: we’ve got research showing both advantages (efficient attention processing) and disadvantages (reduced metacognition) to bilingualism. So, what should we do?

In the end, teachers and parents can draw on research to explore these questions, but we must put many conflicting pieces together to draw the wisest conclusions.

About Andrew Watson

About Andrew Watson