NeuroscienceNews.com has published its “Top 20 Neuroscience Stories of 2017,” and the list provides helpful — and sometimes surprising — insight into current brain research.

Taken together, these stories add up to 5 important headlines.

Headline 1: Neuroscience can tell us such cool stuff!

Gosh darnit: people who swear more are more likely to be honest, and less likely to be deceptive. Dad gummity.

If music literally gives you chills, you might have unusual levels of connectivity between your auditory cortex and emotional processing centers.

People with very high IQs (above 130) are more prone to anxiety than others.

A double hand transplant (!) leads to remarkable levels of brain rewiring (!).

Forests can help your amygdala develop, especially if you live near them.

When you look a baby in the eyes, your brain waves just might be synchronizing.

Headline 2: Your gut is your “second brain”

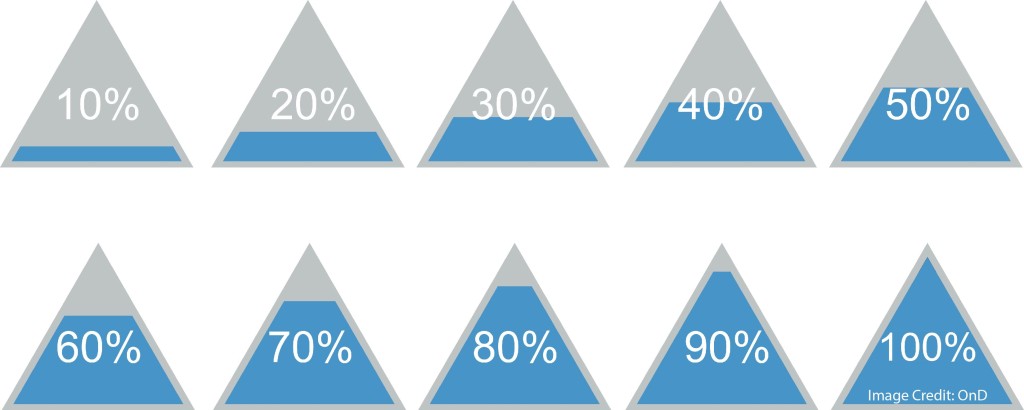

Amazingly, fully one quarter of the 20 top stories focus on the connection between the brain and the digestive system. For example:

- Traumatic Brain Injury Causes Intestinal Damage

- Research Suggests Connection between Gut Bacteria and Emotion

- New Light on Link between Gut Bacteria and Anxiety

- Your Mood Depends on the Food You Eat

- Gut Microbes May Talk to the Brain through Cortisol

This “aha” moment — our guts and our brains are deeply interconnected! — happens over and over, and yet hasn’t fully been taken on board in the teaching and understanding of neuroscience.

Teachers should watch this research pool. It will, over the years, undoubtedly be increasingly helpful in our work.

Headline 3: Neuroscience and psychology disagree about definitions of ADHD

A psychologist diagnoses ADHD by looking at behavior and using the DSM V.

If a student shows a particular set of behaviors over time, and if they interfere with her life, then that psychologist gives a diagnosis.

However, a 2017 study suggests that these ADHD behaviors might be very different in their underlying neural causes.

Think of it this way. I might have chest pains because of costochondritis — inflammation of cartilage around the sternum. Or I might have chest paints because I’m having a heart attack.

It’s really important to understand the underlying causes so we get the treatment right.

The same just might be true for ADHD. If the surface symptoms are the same, but the underlying neural causes are different, we might need differing treatments for students with similar behavior.

By the way, the same point is true for anxiety and depression.

Headline 4: Each year we learn more about brain disorders

Alzheimer’s might result, in part, from bacteria in the brain. Buildup of urea might result in dementia. Impaired production of myelin might lead to schizophrenia. Oxidative stress might result in migraines.

Remarkably, an immune system disorder might be mistaken for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. (Happily, that immune system problem can be treated.)

Headline 5: For teachers, neuroscience is fascinating; psychology is useful

If you’re like me, you first got into Learning and the Brain conferences because the brain — the physical object — is utterly fascinating.

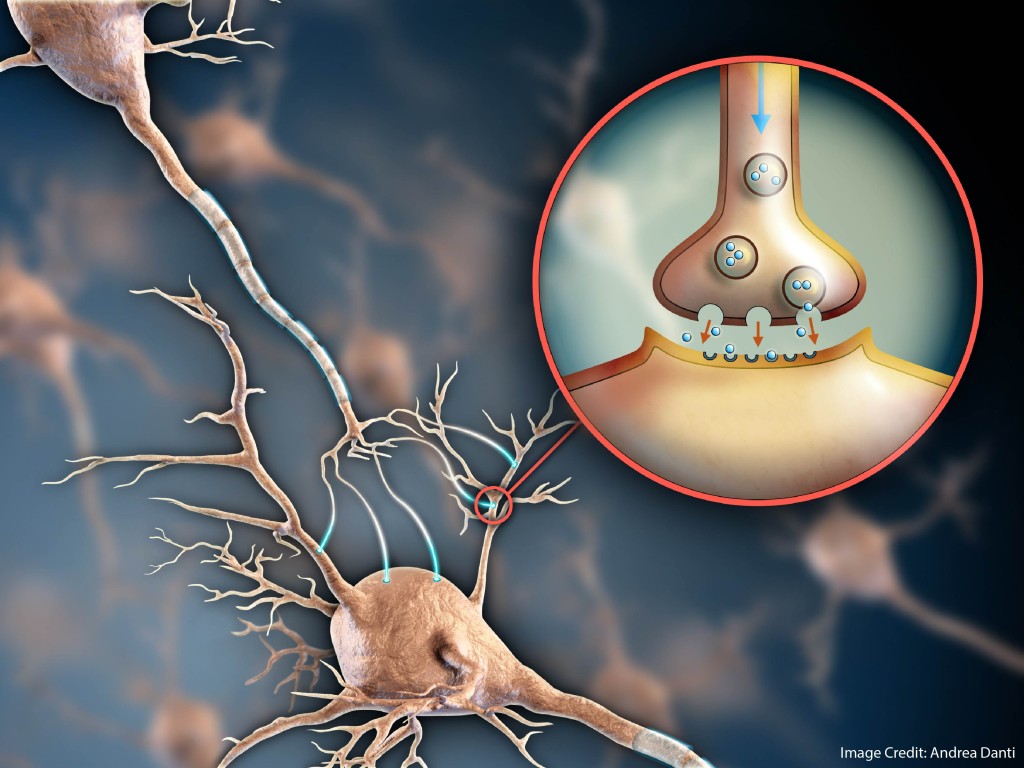

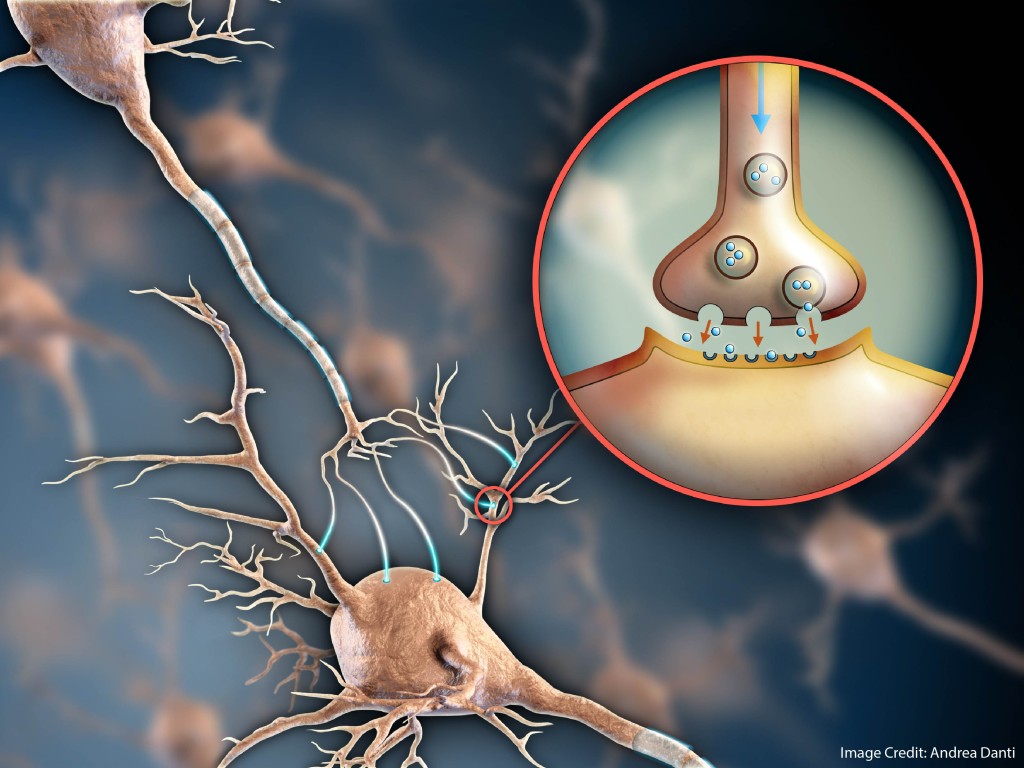

You want to know about neurons and synapses and the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex and the ventral tegmental area. (Ok, maybe not so much with the ventral tegmental area.)

Over all these years, I’ve remained fascinated by neuroscience. At the same time, I’ve come to understand that it rarely offers teachers concrete advice.

Notice: of the twenty headlines summarized above, only one of them really promises anything specific to teachers. If that ADHD study pans out, we might get all sorts of new ideas about diagnosing and treating students who struggle with attention in school.

The other 19 stories? They really don’t offer us much that’s practical.

The world of psychology, however, has all sorts of specific classroom suggestions for teachers. How to manage working memory overload? To foster attention? To promote motivation?

Psychology has concrete answers to all these questions.

And so, I encourage you to look over these articles because they broaden our understanding of brains and of neuroscience. For specific teaching advice, keep your eyes peeled for “the top 20 psychology stories of 2017.”

About Andrew Watson

About Andrew Watson

![AdobeStock_121864954 [Converted]_Credit](https://braindevs.net/blog//wp-content/uploads/2018/01/AdobeStock_121864954-Converted_Credit-1024x410.jpg)