I recently sat on a panel exploring the question “what’s next in our field?” Where should we be going as we try to apply cognitive science (broadly) to the field of education (broadly)? Perhaps it’s helpful to share some ideas we discussed…

But First…

Before we think about next steps, I wonder if we have a clear enough idea of the current state of “our field.” I myself am not always clear which topics are within our purview and which are not.

For example: I recently came across an article exploring the ASTONISHING cognitive benefits of improving air quality in schools. In this research pool, cleaner air led to higher test scores (as well, of course, as important health benefits).

- On the one hand, this question connects research with academic and cognitive performance: it seems like an obvious part of “the field.”

- On the other, the research here focuses on lung function, and requires lots of technical knowledge about HEPA filters and “parts per million.” None of my training in education, psychology, and neuroscience research prepares me to evaluate the relationship between mold spores and math performance.

- On the other other hand: neuroscience is itself a highly specialized kind of biology. Why shouldn’t our field include other kinds of highly specialized biology — like, say, research into lung function and air quality?

So, my first concern is: I don’t know what’s next in our field because I’m not sure what our field currently IS.

A related problem follows on this first one: how do all these topics connect to each other? The topic of mindfulness clearly fits within the field. So does reading instruction for dyslexic students. But: how should I think about connecting those two topics? Where does generative drawing fit? Or cultural differences in the relationship between students and teachers? The best way to ask questions? Or, technology and AI? Given the enormous number of topics, how can we think about the almost infinite number of intersections and interactions?

My wise colleague Glenn Whitman recently gathered together several representations of different parts of “the field.” We could start with a comprehensive LIST put together by Evidence Based Education.

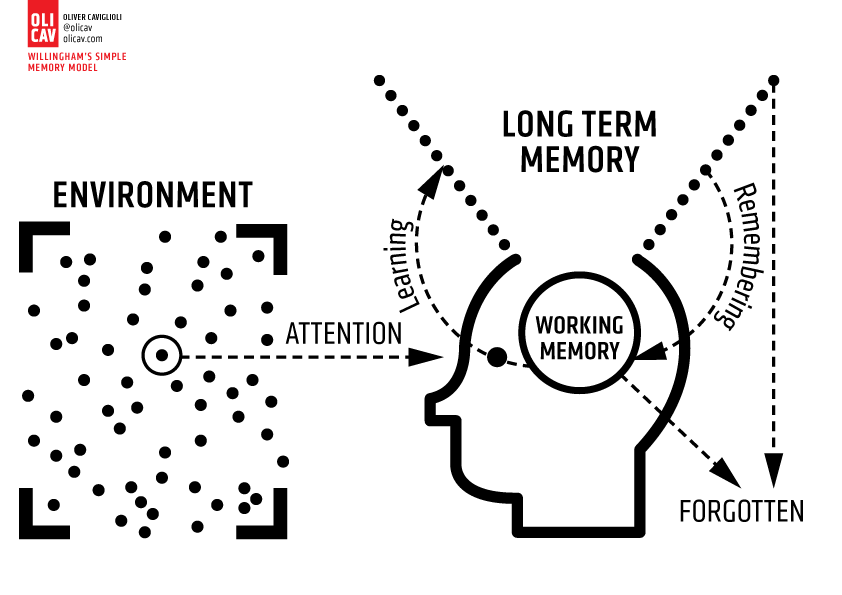

We could counsider Oliver Caviglioli’s revision of Dan Willingham’s “simple model of cognition”:

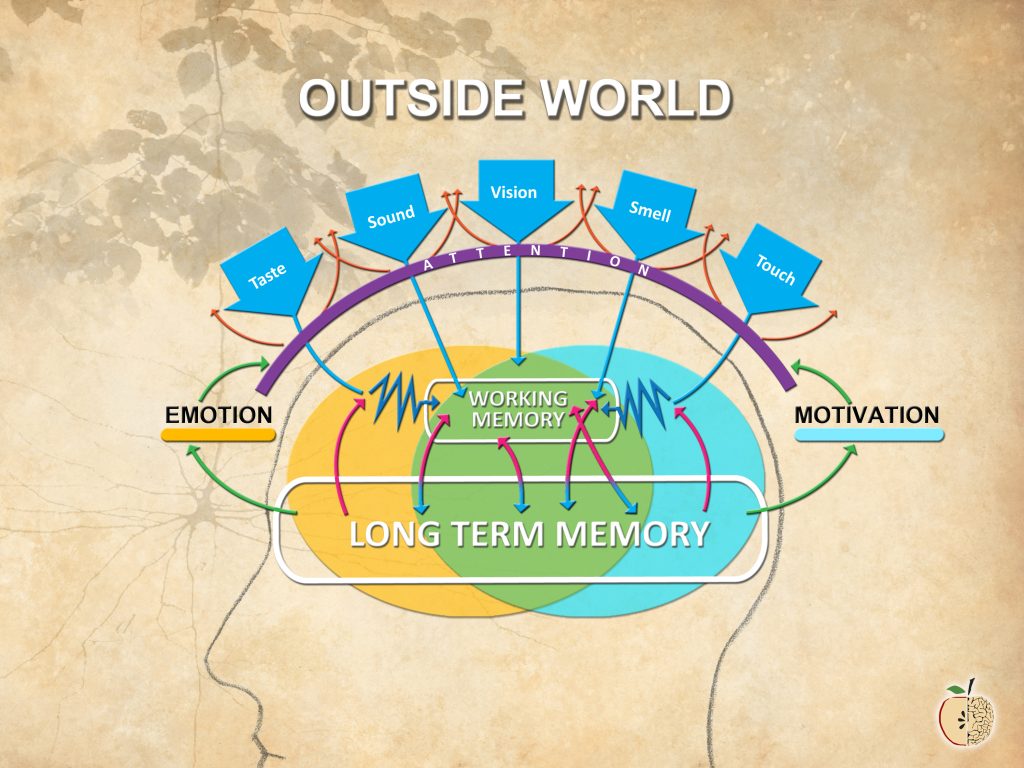

Here’s my own attempt to add affective processes (emotion and motivation) to a more cognitive model (attention and memory).

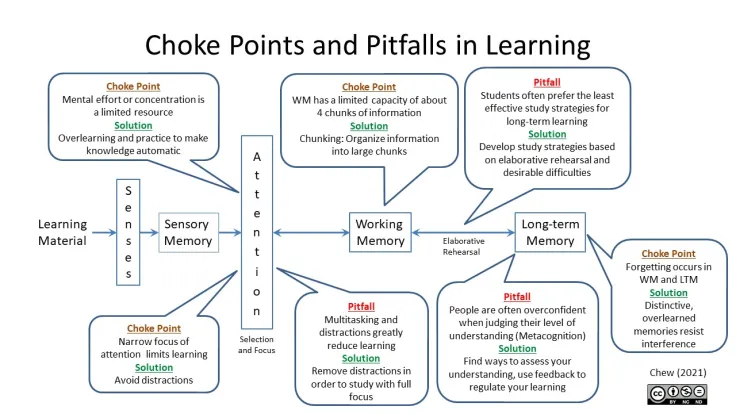

Or we could reframe these concepts with Stephen Chew’s model, that looks at difficulties at each stage in this process:

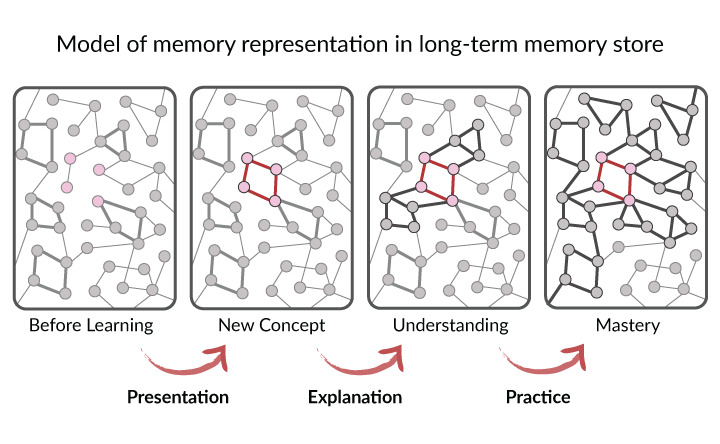

Or Efrat Furst’s representation of memory and schema formation:

But none of these models envisions human development. Or the role of the physical body in learning. Or differences among disciplines. Or technology…

Broadly speaking, before we start considering where we go, I’d like to have a better idea of where we are. And: how “we” all relate to each other.

But Wait: Another Thought…

The question “what’s next” implies that we’re nearly done with the tasks on our to-do list. It has a vibe: “We’ve got this project almost wrapped up–what should we move on to now?”

I myself think we are nowhere near being done with the work we’ve already got. As far as I can tell:

- Relatively few teachers know much about working memory, or think about it as they plan;

- Many (MANY) teachers still believe in various neuromyths/psychomyths;

- We don’t often talk about the goal of education; so we have no common basis from which to think about the practice of teaching;

- The precise way to use retrieval practice with 6th graders learning science in a Montessori program in Madrid is probably not the right way to use retrieval practice to help 12th graders with ADHD learn calculus at a military academy in Reykjavik.

If teachers at my school chose even one of those topics, we would need several months of work to make lasting progress and change — because we have LOTS of other stuff to do! I’m so busy helping my students understand the poetic debate between Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen (and grading all their analytical paragraphs) that I have very little bandwidth left to invest in new approaches.

I hope that we shift from thinking about this work as something that we do, cross off the list, and move on to the next thing. Instead, we need to steep in any one of these topics for…well…months at a minimum.

Here’s an example. I’ve done some work over the years with a school out in Western Massachusetts. Each year, they pick a PD topic and add it to a list of three. They then keep that topic under explicit discussion and practice for THREE YEARS. When they’ve had that much time to think it over, they cycle that one out and add a new one.

I don’t know if that precise schedule will work for everyone, I do think that time horizon will be much likelier to have an effect than a more typical approach: “we talked about AI last month, so THIS month we’ll be thinking about trauma…”

Okay, NOW we can talk about next frontiers.

Sorry, Hold Up for a Second…

Before we move on to the next topic, I think we should get better at persuading people to join our team.

Because you attend Learning and the Brain conferences, and you’re reading this blog, you probably already believe that a cognitive science + research approach to education makes lots of sense. But let’s be honest: many, MANY people do NOT share our belief.

And: the teaching practices supported by cognitive science provoke genuine alarm–even revulsion–in other educational spheres. Direct instruction and retrieval practice and cold calling may make sense within a psychology-focused approach to instruction, but they often prompt real dismay among colleagues who do not share our starting point. (Heck: not every speaker at a Learning and the Brain conference would champion even these approaches.)

I honestly don’t know where or how to change people’s minds; that’s not my specialty at all.

I do worry, however, that the best known public venues for changing minds–say, social media platforms–mostly promote angry shouting and name calling. I myself don’t think that we can insult people enough to cause them to join our team. We need to welcome and befriend them; doing so probably requires lots of listening and curiosity. The more often I call someone a grifter, the less likely I am to persuade them to think the way I think.

If we can’t get people to join us where we are, I don’t know that thinking about the “next frontier” will provide us with much additional benefit.

Back to Where We Started

Although I sat on a panel about “next frontiers” in this field, I don’t really know much about those next frontiers. Instead, I think we should focus on:

- Defining and mapping the field as it currently stands,

- Shifting our timescale: meaningful change takes months and years, and

- Persuading others to join our work with welcoming curiosity.

I don’t doubt that others will have excellent new ideas. Me: I’m still pondering and processing the ideas we’ve already had…