Here’s a practical question: should our students take notes by hand, or on laptops?

If we were confident that one strategy or the other produced more learning – factual learning, conceptual learning, ENDURING learning – then we could give our students straightforwardly useful advice.

Sadly, the research in this field has – in my opinion – produced unhelpful advice because it rests on an obviously flawed assumption.

Happily, Dr. Paul Penn (Twitter handle @Dr_Paul_Penn) recently pointed me to a study with several pertinent benefits.

First, the researchers worked with 10-year-olds, not with adults. Research with college students can be useful, but it might not always help K-12 teachers.

Second, the research took place in the students’ regular classroom, not in a psychology lab. This more realistic setting gives us greater confidence in the research’s applicability.

Third, students took notes in both a science class and in a history class. The disciplinary breadth makes its guidance more useful.

Finally, this study – for reasons that I’ll explain – makes the “obviously flawed assumption” go away.

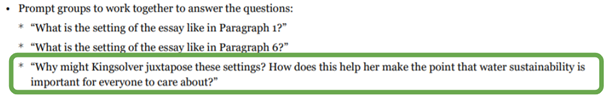

In this post,

I’ll start by explaining the new study.

Then I’ll explain the initial study (with the “obvious flaw”).

Then I’ll explain how the new study – by accident – makes that flaw go away.

I’ll wrap up with the big picture.

The Black Death, and Beyond

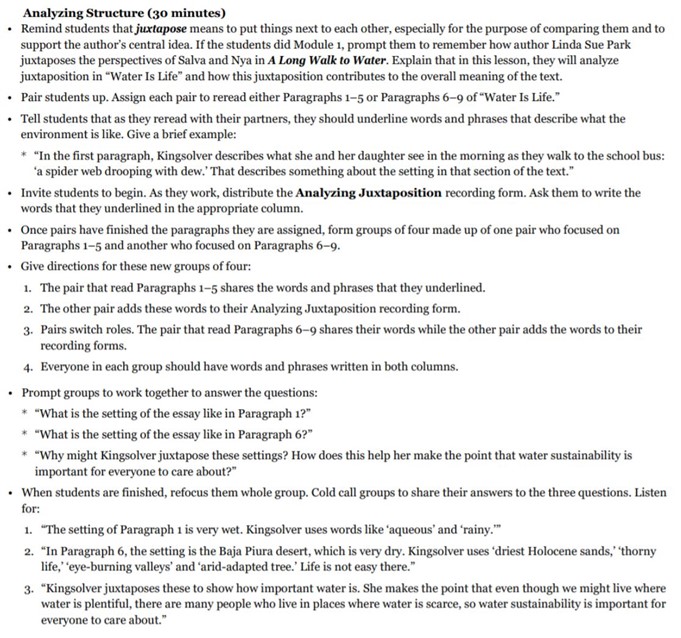

Researchers Simon Horbury and Caroline Edmonds had ten-year-olds watch videos in their history and science classes.

The history videos focused on the Black Death. The science video explored cells.

Students took laptop notes in one class, and handwritten notes in the other.

Immediately after the videos, and then again a week later, students took a multiple choice quiz. Questions covered both factual recall (“Where did the Black Death originate?”) and conceptual understanding (“Why were the wealthy less likely to be afflicted by the plague?”).

To be thorough, researchers even counted the number of words students wrote in their notes. (Believe it or not, this detail will turn out to be important at the end of this post.)

So, did it matter how students took notes?

Yup.

The study measures several variables, but the headline is: in both science and history, taking notes by hand improved learning – especially a week later.

The study includes lots of specifics — conceptual vs. factual, immediate test vs. week-later test — but that summary gets the job done.

Yes, this is a very small study (26 people at its biggest), so we shouldn’t think it’s the final word on the matter. But it offers good reason to believe that handwritten notes help.

Back to the Beginning

Like all research in this field, Horbury & Edmonds’s work rests atop a well-known study by Mueller and Oppenheimer, cleverly entitled “The Pen Is Mightier than the Laptop.”

I’ve written about this study several times before, so I’ll be brief here.

Mueller and Oppenheimer had one group of college students take notes by hand, and another group take notes on a laptop. They found that two variables mattered for learning:

Variable #1: the number of words students wrote. Crudely put: more words in notes resulted in more learning.

This finding isn’t terribly surprising. More writing suggests more thinking; more thinking suggests more learning.

Variable #2: the degree to which students reworded the lecture. Student who put the lecture’s ideas into their own words learned more than those who simply took notes verbatim.

Again, this finding makes sense. If I simply copy down the lecturer’s ideas, I’m not thinking much. If I put them in my own words, well, now I’m thinking more.

So far, so good. No obvious flaws.

Now the study gets tricky.

The students who took handwritten notes wrote FEWER words (that’s bad), so they had to REWORD the lecture (that’s good).

The students who took laptop notes could write MORE words (that’s good), so they ended up copying the lecture VERBATIM (that’s bad).

Which pairing of good+bad is better?

In Mueller and Oppenheimer’s conclusion, handwritten notes resulted in more learning.

It’s okay to write fewer words, as long as you’re rewording as you go. Remember: more rewording = more thinking.

Obvious Flaw

I promised several paragraphs ago to point out the obvious flaw in the study. Here goes:

Mueller and Oppenheimer saw an obvious possibility: if we TRAIN laptop note takers to reword, then they’ll get BOTH benefits.

That is, students who take laptop notes correctly get the advantages of more words and more rewording.

So much thinking! So much learning!

So, the researchers ran the study again. This time they included a third group: laptop note takers who got instructions not to reword.

What happened?

Nothing. Even though they got those instructions, laptop note takers continued to copy verbatim. They still remembered less than their handwriting peers.

The Mueller and Oppenheimer study draws this conclusion: since students can’t be trained to take laptop notes correctly – and they tried! – then handwritten notes are best.

WAIT JUST A SECOND. [Please mentally insert the sound of a record scratch here.]

The researchers told students – ONCE – to change a long-held habit (verbatim copying of notes). When students failed to do so, they concluded that students can’t ever change.

In my own experience, telling my students to do something once practically NEVER has much of an effect.

Students need practice. LOTS of practice. Practice and FEEDBACK. Lots of feedback.

Obviously.

In other words, I think the Mueller and Oppenheimer study contains a conspicuous failure in logic. We shouldn’t conclude that handwritten notes are better. We SHOULD conclude that we should teach students to take laptop notes and reword as they do so.

If they can learn to do so (of course they can!), then laptop notes will be better — because they allow more words AND rewording.

Muller and Oppenheimer’s own data make that the most plausible conclusion.

Conflicting Messages

To review:

The Horbury & Edmonds study suggests that handwritten notes are better.

The Mueller and Oppenheimer study suggests (to me, at least) that laptop notes will be better – as long as students are correctly trained to reword notes as they go.

Which advice should we follow?

My answer comes back to that obscure detail I noted in parentheses.

Horbury and Edmonds, you may remember, counted the number of words students wrote. Unlike the college students, who can type faster than they write, 10-year-olds don’t.

They wrote basically the same number of words by hand as they did on the laptop.

Here’s the key point: as long as students write as fast as they type, the hypothetical advantage that I predict for college laptop note-takers simply won’t apply to younger students.

After all, laptop notes provide additional benefit only if students write more words. These younger typists don’t write more words.

Since handwritten notes produce more learning, let’s go with those!

Final Thoughts

In this post, I’ve considered two studies about note taking and laptops.

In truth, several studies explore this field. And, unsurprisingly, the results are a bit of a hodge-podge.

If you want a broader review of research in this field, check out this video from Dr. Paul Penn, who first pointed me to the Horbury and Edmonds study:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TXLHxf__poE

Given the research we have, I DON’T think we can make emphatic, confident claims.

But, based on this study with 10-year-olds, I’m much more open to the possibility that handwritten notes are — at least in younger grades — the way to go.

Horbury, S. R., & Edmonds, C. J. (2021). Taking class notes by hand compared to typing: Effects on children’s recall and understanding. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 35(1), 55-67.

Mueller, P. A., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2014). The pen is mightier than the keyboard: Advantages of longhand over laptop note taking. Psychological science, 25(6), 1159-1168.