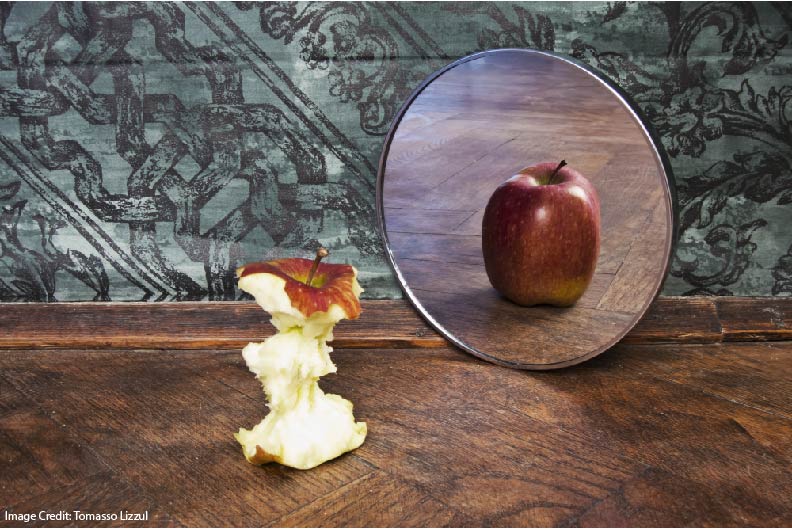

We’ve seen enough research on retrieval practice to know: it rocks.

When students simply review material (review their notes; reread the chapter), that mental work doesn’t help them learn.

However, when they try to remember (quiz themselves, use flashcards), this kind of mental work does result in greater learning.

In Agarwal and Bain’s elegant phrasing: don’t ask students to put information back into their brains. Instead, ask them to pull information out of their brains.

Like all teaching guidance, however, the suggestion “use retrieval practice!” requires nuanced exploration.

What are the best methods for doing so?

Are some retrieval practice strategies more effective?

Are some frankly harmful?

Any on-point research would be welcomed.

On-Point Research

Here’s a simple and practical question. If we use pop quizzes as a form of retrieval practice, should we grade them?

In other words: do graded pop quizzes result in more or less learning, compared to their ungraded cousins?

This study, it turns out, can be run fairly easily.

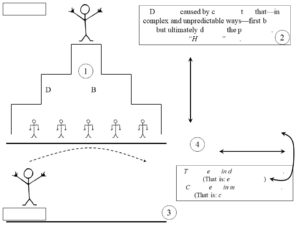

Dr. Maya Khanna taught three sections of an Intro to Psychology course. The first section had no pop quizzes. In the second section, Khanna gave six graded pop quizzes. In the third, six ungraded pop quizzes.

Students also filled out a questionnaire about their experience taking those quizzes.

What did Khanna learn? Did the quizzes help? Did grading them matter?

The Envelope Please

The big headline: the ungraded quizzes helped students on the final exam.

Roughly: students who took the ungraded pop quizzes averaged a B- on the final exam.

Students in the other two groups averaged in the mid-to-high C range. (The precise comparisons require lots of stats speak.)

An important note: students in the “ungraded” group scored higher even though the final exam did not repeat the questions from those pop quizzes. (The same material was covered on the exam, but the questions themselves were different.)

Of course, we also wonder about our students’ stress. Did these quizzes raise anxiety levels?

According to the questionnaires, nope.

Khanna’s students responded to this statement: “The inclusion of quizzes in this course made me feel anxious.”

A 1 meant “strongly disagree.”

A 9 meant “strongly agree.”

In other words, a LOWER rating suggests that the quizzes didn’t increase stress.

Students who took the graded quizzes averaged an answer of 4.20.

Students who took the ungraded quizzes averaged an answer of 2.96.

So, neither group felt much stress as a result of the quizzes. And, the students in the ungraded group felt even less.

In the Classroom

I myself use this technique as one of a great many retrieval practice strategies.

My students’ homework sometimes includes retrieval practice exercises.

I often begin class with some lively cold-calling to promote retrieval practice.

Occasionally — last Thursday, in fact — I begin class by saying: “Take out a blank piece of paper. This is NOT a quiz. It will NOT be graded. We’re using a different kind of retrieval practice to start us off today.”

As is always true, I’m combining this research with my own experience and classroom circumstances.

Khanna gave her quizzes at the end of class; I do mine at the beginning.

Because I’ve taught high school for centuries, I’m confident my students feel comfortable doing this kind of written work. If you teach younger grades, or in a different school context, your own experience might suggest a different approach.

To promote interleaving, I include questions from many topics (Define “bildungsroman.” Write a sentence with a participle. Give an example of Janie exercising agency in last night’s reading.) You might focus on one topic to build your students’ confidence.

Whichever approach you take, Khanna’s research suggests that retrieval practice quizzes don’t increase stress and don’t require grades.

As I said: retrieval practice rocks!

![Prior Knowledge: Building the Right Floor [Updated]](https://www.learningandthebrain.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/AdobeStock_227486358_Credit-1024x631.jpg)