As you know from reading this blog, cognitive psychology offers teachers dozens of helpful ideas.

We’re all better teachers when we enhance executive function and foster attention and manage working memory load.

Alas, over the years, many brain myths have gathered to clutter our thinking.

No, we don’t use only 10% of our brains.

No, the “learning pyramid” doesn’t tell you anything useful. (It doesn’t even make sense.)

No, learning styles aren’t a thing.

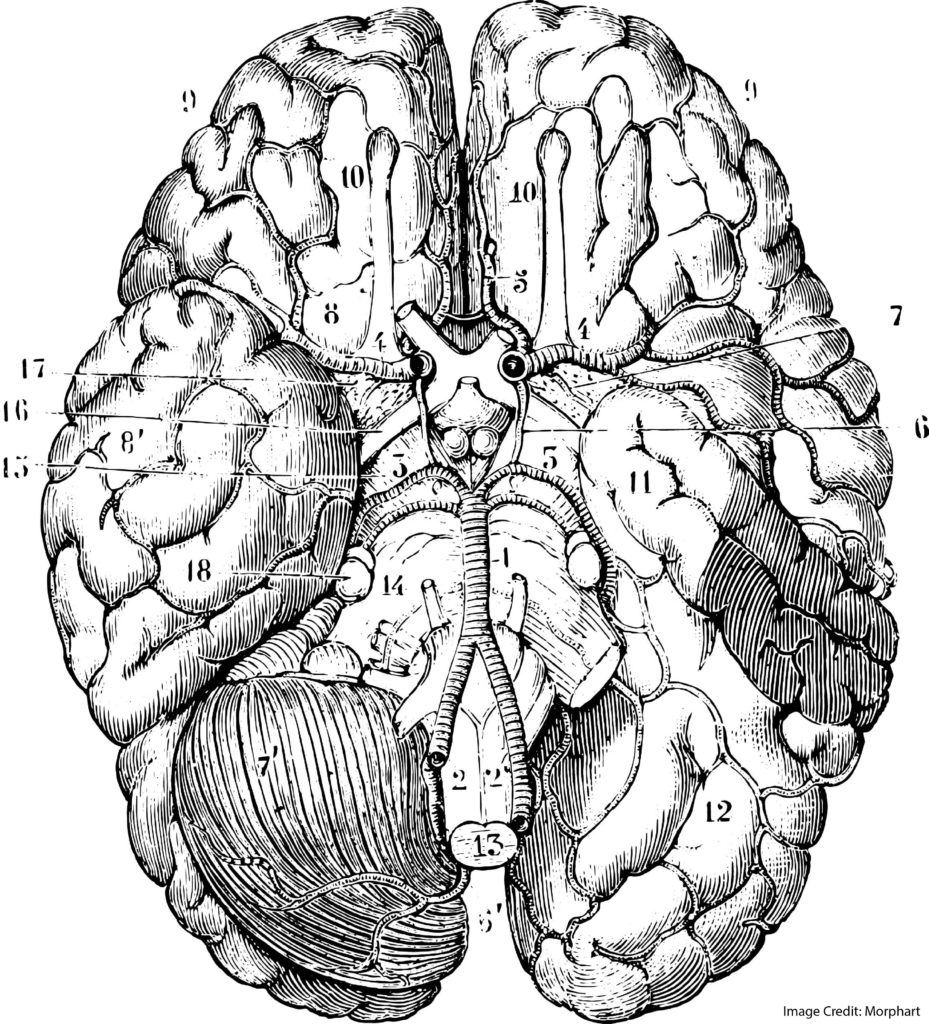

“Left-Brained” Skepticism

You might think I’m using my “rational, left-brained thinking skills” to offer these skeptical opinions.

Alas, the whole left brain/right brain distinction is itself another myth.

In some cases, brain functions happen more on one side of the brain than the other. But, even when we’re undertaking that particular function, we’re using brain regions from all over to get the mental job done.

A case in point…

“Lateralized” Language. Or, not.

Dedicated left-brain/right-brain advocates often point to language function to make their case.

For instance, Broca’s area — which helps us produce coherent speech — is in the left hemisphere. (So is Wernicke’s area, which helps us understand speech.)

Given these truths, they argue that speech is a “lateralized” brain function. In other words, it takes place in one hemisphere of the brain, not the other.

This claim, however, suffers from several flaws.

In the first place, Broca’s area is in the left hemisphere for 95% of right-handed people. But, that’s not 100%. And, that percentage falls to 50% for left-handed people.

Not so left-lateralized after all.

A second problem: language learning requires lots of right-hemisphere participation.

In a recent study, activity in the right hemisphere predicted participants’ later success in learning Mandarin. In fact, “enhanced cross-hemispheric resting-state connectivity [was] found in successful learners.”

Phrases like “cross-hemispheric resting-state connectivity ” might cause your eyes to glaze over. But, this key point jumps out: we can’t meaningfully ascribe language function to one hemisphere or another.

All complex mental activities require activation across the brain.

Teaching Implications

If you get teaching advice that you should do XYZ because a particular mental function takes place in a particular hemisphere: STOP.

Almost certainly, this claim

a) isn’t meaningfully accurate, and

b) comes from sources who don’t know as much about brains as they think they do.

Instead, ask yourself: does this guidance make sense even without claims about lateralization.

If yes, go ahead! If no, don’t bother.

In other words: use your whole brain and be skeptical.