What’s the best way for students to practice? Should they review information or procedures? Or, should they try to remember or enact them?

We’ve got scads of research showing that retrieval practice helps brains learn.

That is: if I want to learn the definition of a word I’ve studied, I should try to recall it before I look it up again. (For a handy review, check out RetrievalPractice.org.)

So, we know that retrieval practice works. But: why? What’s happening in the brain that makes it work?

Two Possibilities

We’ve got several possible answers, but let’s focus conceptually on two of them.

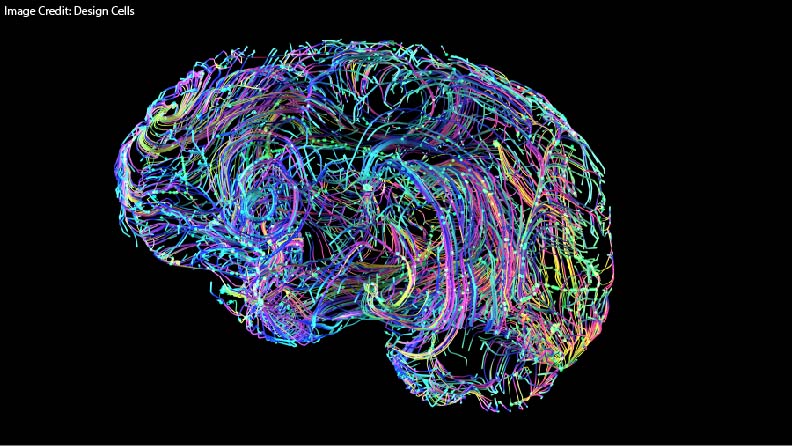

Increased neural connections

Reduced neural connections

That is: when I engage in retrieval practice, I push myself to remember X. But it takes me a while to get to X. I might start with S, and then wonder about Y. Perhaps I’ll take a detour to gamma. Eventually, I figure out X.

During this mental work, I both remember X and connect X to all those other (rejected) possibilities: S and Y and gamma. By increasing connections among all these topics, I make it easier to remember X later on. If I accidentally think about S, I can quickly get to X.

Or, maybe the opposite process happens.

The first time I try to remember X, I waste mental time with S and gamma. But, the next time, I’ve gotten better at remembering X, and so I take less time to get there. I can “prune away” extraneous mental connections and thereby simplify the remembering process.

In this account, by reducing the steps involved in remembering X, I see the benefits of retrieval practice.

We Have a Winner (?)

A research team in Europe took on this question, and looked at several studies in this field.

Whenever you start looking at neuroscience research, you should brace yourself for complexity. And, this research is no exception. It’s REALLY complicated.

The short version goes like this. Van den Broek and colleagues identify several brain regions associated with memory formation and retrieval. You might have heard of the angular gyrus. You might not have heard of the inferior parietal lobe. Anyway, they’ve got a list of plausible areas to study.

They then asked: did retrieval practice produce more activity in those regions (compared to review)? If yes, that finding would support the “increased connection” hypothesis.

Or, did retrieval practice result in less activity in those regions? That finding would support the “reduced connection” hypothesis.

The answer? Less activity. At least in the studies van den Broek’s team analyzed, the “reduced connection” hypothesis makes better predictions than the “increased connection hypothesis.”

To be clear: I’ve left out a few other explanations they consider. And: I’ve simplified this answer a bit. If you’re intrigued, I encourage you to look at the underlying review: it’s FASCINATING.

To Sum Up

We have at least a tentative idea about why retrieval practice works.

And: we have SUPER PERSUASIVE evidence that retrieval practice works.

Even though we’re not 100% sure about the why, we should — as teachers — give our students as many opportunities as we can to retrieve.