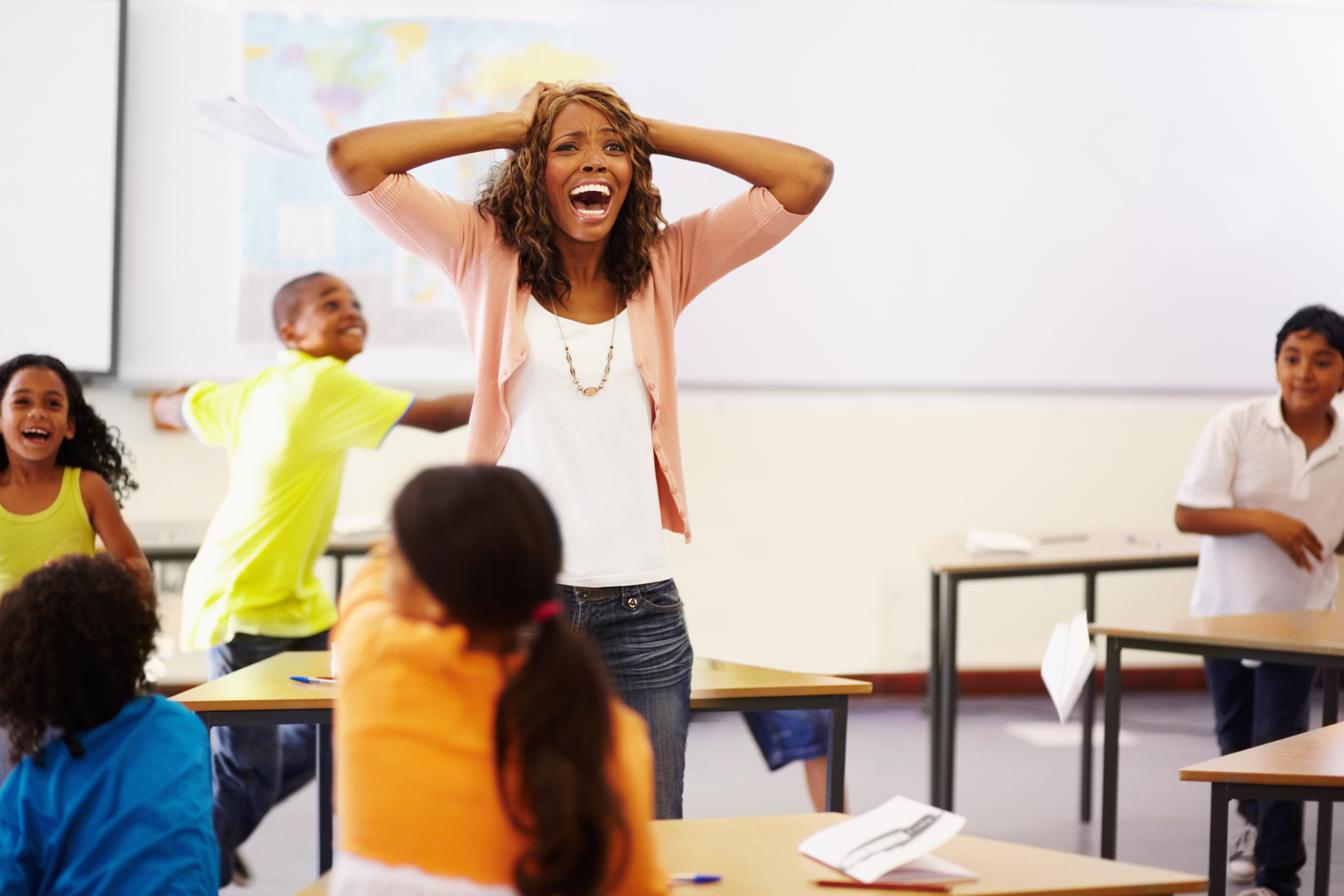

Let’s face it: teaching is hard.

I’ve been a classroom teacher for roughly 20 years — how do I count summer school? — and I still find the work exhillarating, exhausting, baffling, uplifting, frustrating, humbling, and joyous.

And that was Tuesday.

And: I think I’m not the only one who finds teaching to be an extra-ordinary challenge. I mean, don’t get me wrong, I love it. But GOSH it’s hard.

This hard-won experience leads me — and perhaps you — to two conclusions:

First: people who haven’t taught in the classroom don’t fully understand the challenges of the work.

Until you’ve tried to follow a scrupulously-devised lesson plan despite the fact that an un-announced fire-drill is in progress, two students have switched sections, three don’t have their notebooks, and four don’t think the cell-phone policy applies at just this moment…you just don’t really know.

How could you? It’s “Misson Impossible: Chalkdust” in here.

Second: I need all the help I can get.

No, really.

You’ve got some research that might …

… help me create a more effective lesson plan?

… explain how attention really works?

… suggest study strategies to help my students learn?

… foster motivation, at the beginning of a lesson on grammar?

I’m all ears. Please. I’m practically begging here…

My Learning and the Brain Journey

I attended my first LatB conference in 2008; the topic was The Science of Attention.

I IMMEDIATELY realized that this conference was just what I needed. So much wisdom and advice. So many compelling suggestions.

And, so many graphs and pictures of brains!

I returned to the classroom and started rethinking everything.

What should be rewrite policy be?

Should my classroom decorations be in primary colors?

What’s the right number of new vocabulary words to teach per class?

I had research-y answers to all those questions.

After several years of attending conferences, I went back to grad school and got a degree combining education, psychology, and neuroscience.

And, in addition to teaching, I started training other teachers.

Now I offered LOTS of advice of my own:

Because working memory does this, teachers should do that.

Because long-term memory benefits from this, teachers should do that.

Because stress affects this…you get the picture.

Many teachers appreciated all this guidance. But some obviously didn’t.

For whatever reason, they just didn’t want to do what I was telling them to do!

I was genuinely surprised; after all, I knew I was right because the research said so!

“The Big Ask”

Over time, I’ve come to realize that those teachers didn’t want to do what I was telling them — and “what the research said” — because I had forgotten the first lesson described above.

I mean: yes (lesson #2), “I need all the help I can get.” So, research-based advice MIGHT help.

But also,

Yes (lesson #1), “people who haven’t taught in the classroom don’t fully understand the challenges of the work.” So, research-based advice might not apply to this classroom, this topic, this teacher, or this student.

In other words,

When I say to teachers, “you should change the way you teach because research says so, ” I’m making a REALLY BIG ASK.

After all, those students are ultimately their responsibility, not mine.

Yes, I have taught — but I teach English to 10th graders at a very selective school. I should be very careful when offering guidance to, say …

… 2nd grade teachers who work with struggling readers, or

… those with lots of students on the Autism spectrum, or

… teachers who work in different cultures.

Because I do know research well, and I know classrooms fairly well, I can make those Big Asks. But I should be humble about doing so. And I should be respectful when a teacher says, “your ‘research-based advice’ …

… conflicts with our school’s mission, or

… might work with college students, but probably won’t work with 2nd graders, or

… requires personality traits that I don’t have.”

Yes, I think teachers should listen thoughtfully to the guidance that comes from research. And, I think those of us who cite research should listen thoughtfully to the classroom specifics, and the experience, of teachers.

Teachers who resist ‘research-based advice’ might seem “stubborn,” but they also might be right.

The Story Behind the Story

In last week’s blog post, I summarized research about using gestures to teach specific science concepts. I also sounded a few notes of caution:

I don’t fully understand the concept of “embodied cognition,” and

I worry that a few very specific studies will be used to insist that teachers make broad changes to our classroom work.

Even as I wrote that post, I could hear colleagues’ voices in my head: “why are you always so grouchy? Why don’t you listen when people with PhDs say ‘this is the Next Important Thing’?”

The answer to those question is this week’s blog post.

I’m ‘grouchy’ because I worry our field is constantly making Big Asks of teachers.

We often make those Asks without acknowledging a) the limits of our research knowledge, and b) the breadth of teachers’ experience.

I am indeed optimistic about combining cognitive psychology research with teacherly experience to improve teaching and foster learning.

To make that combination work, we should respect “stubborn” teachers by making Respectful Asks.