Here’s a chance to test your knowledge about the teaching implications of cognitive science. Which answer would you pick to this question?

After teaching students the names of the branches of the US government and what each does, which would be the most effective way a teacher could help their students remember this information?

A) Have students read the facts for 10 days at the beginning of class.

B) Have students copy the facts into a notebook where they can reference them as needed.

C) Have students take a once-a-week quiz for 10 weeks where they recall the facts from memory.

D) Have students participate in a review game where they have to recall the facts from memory several times in one class period.

As you think about that question — which I’ll answer later in the post — ask yourself: what basic principle of learning informs your choice?

How Can We Discover What Teachers Know?

For several years now, Deans for Impact have worked to improve teacher education. In particular, they want schools of education to emphasize well-established principles from cognitive science.

They have done lots of great work to further this mission — including publishing this invaluable resource on the science of learning. (Quick: download it now!)

Of course, if they — and we — are going to help teachers improve, we have to know what teachers already believe and do. If teachers don’t believe in learning styles theory, then we don’t have to debunk it. (Alas, lots of teachers do.)

To answer that question, Deans for Impact developed a 54 question assessment of teacher beliefs, and administered it to 1000+ teachers in the fall of 2019. The question you answered above is one of those 54 questions.

Based on the answers they got, they now have a much better idea of typical beliefs and misunderstandings. As they note, however, these teachers are enrolled in education schools that are interested in cognitive science. So:

“the data generated from this assessment is more likely to overstate what most teacher-candidates know about learning science.”

With that caveat in mind, what did they learn?

What Do Teachers Know about Cognitive Science?

Unsurprisingly, D4I found a mixed bag.

In some categories, teachers-in-training did quite well. In particular, they had good information about the importance of building, and the right ways to build, feedback loops.

That’s really good news, of course, because feedback is so important.

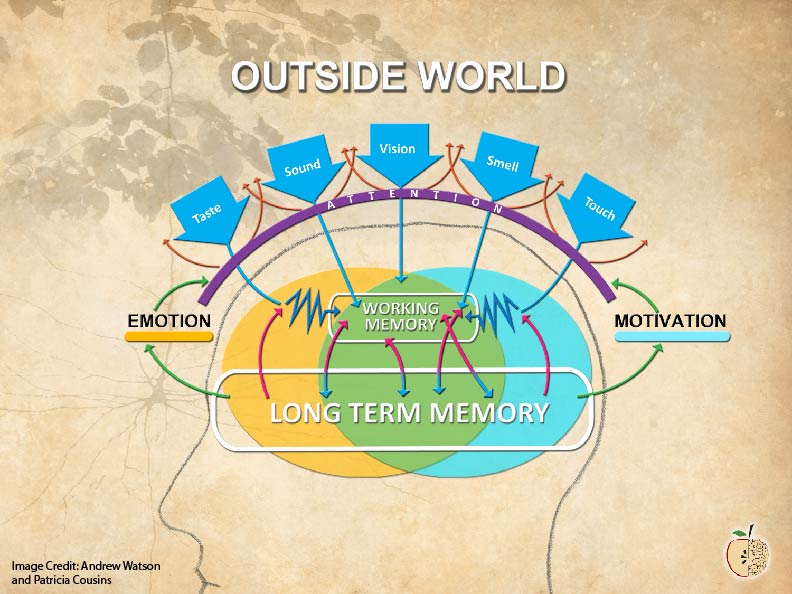

In general, teachers also had a clear understanding that prior knowledge matters a lot. When students lack relevant background knowledge, they struggle mightily to learn.

Sadly, teachers overestimated the possibility of critical thinking.

Of course we want our students to have strong critical thinking skills. But, for the most part, those skills don’t exist generically. That is: I must have a great deal of specific content knowledge before I can think critically about a particular topic.

If that claim seems surprising or suspect, try to answer this question: are Dreiser’s novels more like Wharton’s or Dos Passos’s? Unless you know A LOT about Dreiser and Wharton and Dos Passos (and novels), you’ll struggle to have much to say.

Needs Improvement

Alarmingly, teachers-in-training scored only 33% on questions relating to “practicing with a purpose.” We learn almost everything by practicing in the right way, so this finding should encourage us to focus quite emphatically on this research field.

To do that, let’s return to the question at the top of this post. What kind of practice would help students remember information about branches of the US government?

A) Have students read the facts for 10 days at the beginning of class.

This choice spaces practice out. That’s good. But, it doesn’t allow for active recall. As we know from the world of retrieval practice, recall creates more lasting memories than mere review.

B) Have students copy the facts into a notebook where they can reference them as needed.

This choice is a dud. It requires students to do minimal processing (“copying”!), and to do it once. Nothing to see here. Move along.

C) Have students take a once-a-week quiz for 10 weeks where they recall the facts from memory.

Choice C requires recall (a quiz). And, it includes spacing (over 10 weeks!). Spacing + retrieval looks great!

D) Have students participate in a review game where they have to recall the facts from memory several times in one class period.

This option sounds fun — it’s a game! And, it includes active recall. But, alas, active recall combined with fun isn’t as beneficial as active recall combined with spacing.

So, we might be tempted by option D — in fact, 60% of teachers-in-training chose it. Only 13% opted for choice C: the one best supported by cognitive science. (By the way: if you’re interested in combining retrieval practice with spacing, check out this research.)

In Sum

Generally speaking: keep Deans for Impact on your radar. They’re a GREAT (and greatly reliable) resource for our work.

Specifically speaking: this most recent report lets us know where we should focus most urgently as we help teachers improve our profession.