We teachers benefit A LOT from research-based guidance, but we do have to acknowledge a few drawbacks:

We can easily find LOTS of contradictory studies out there — so confusing!

The students or curriculum being researched might not be a good match for our own — so puzzling!

And

Research takes a long time — so frustrating!

In other words: we REALLY needed advice about online teaching during the pandemic-related Zoominess. But — because “research takes a long time” — we just didn’t have lots of relevant studies to guide us.

Of course, we’re now starting to get those studies we needed a few years ago: better now than never, I say.

To be sure, few of us hope to return to full-time online teaching. But:

Some people do this work for a living (I have a friend who devotes herself to this work).

Some school districts use Zoom during snow storms (or eclipses).

Sometimes, online teaching is just practically required. I recently led a 2 hour PD workshop in Singapore…while I was in London.

So, we still benefit from learning about this online teaching research — even if most of us hope we’ll use it only rarely.

What useful nuggets have come to the surface?

Defeating the Blahs

If you’ve taught online, you know how quickly the blahs set in.

No matter how interesting our content or how lively our presentation, the students quickly settle into polite apathy.

Screens wink off.

We can practically SEE the mind-wandering in thought bubbles above our students’ heads.

Is there anything we can do to counteract this seemingly inevitable lethargy?

A research team in Germany set out to investigate this question.

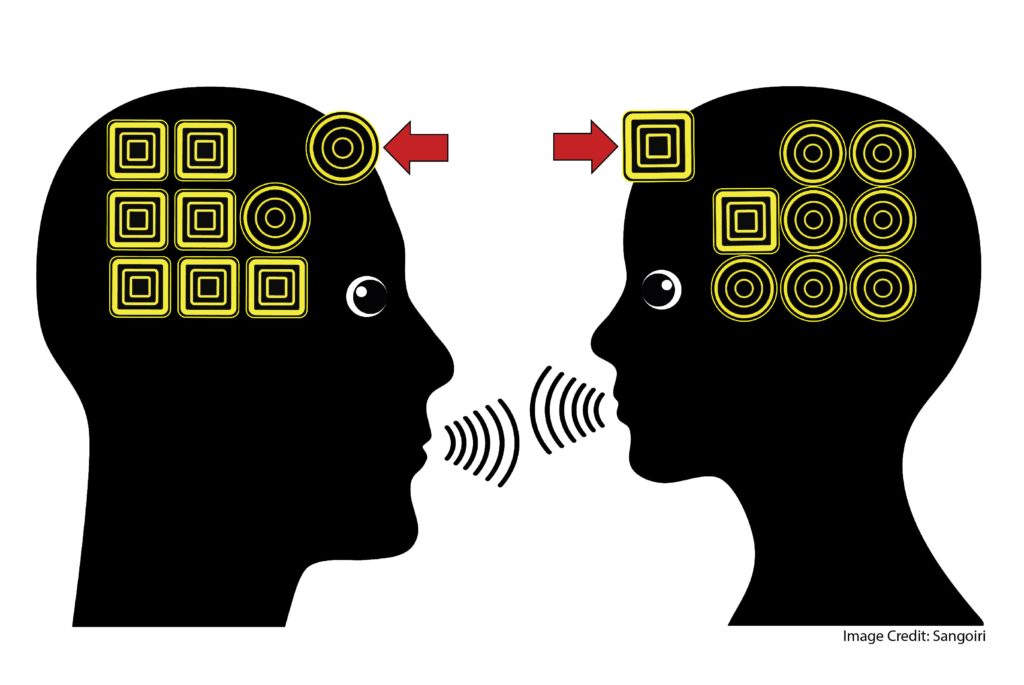

Specifically, they wanted to know if “interaction-enhanced online teaching” could overcome the blahs.

What, you ask, is “interaction-enhanced online teaching,” exactly?

The researchers used several interactive techniques:

Students in this group kept their cameras on,

answered questions at random times during the lecture,

and took a quiz on the material at the conclusion of the lecture.

So, did these changes help?

The Envelopes, Please…

To answer this question, researchers focused much less on students’ learning and much more on the students attention. Specifically, they focused on a sub-component of attention called “alertness.”

This subcomponent means exactly what you think it does: “how much physiological energy is the student experiencing at this moment?” (Teachers typically face two “alertness” problems: too much [students running around with scissors] or too little [students falling asleep, with or without scissors].)

To track alertness, the research team measured all sorts of variables: the students’ heartbeat, the amount of cortisol in their saliva, and their own self-ratings.

So, did always-on cameras and random questions affect these variables? Specifically, did these students show higher alertness levels than others who simply watched the lecture — without the alertness bells-n-whistles?

The short answer is: yup.

Because those variables (heart rate, cortisol) are frankly rather obscure, it probably doesn’t help to rattle off the numbers. (You can check them out in the study itself.)

But the trends are clear: all that alertness enhancing did the trick. Students had more energy during the online presentation.

Classroom Implications

In my view, this study has lots going for it.

First, its recommendations just make sense.

Both daily experience and a decade or so of research shows that students who have to pay attention — they might have to answer a question soon! — remain alert and learn more.

Second, its recommendations are easy to enact. While creating random questions and post-class retrieval practice might take some additional effort, doing so isn’t an enormous task.

The topic of “keeping the camera on” creates controversy in some places — and I can imagine circumstances where it’s not appropriate. But I suspect in most cases, a “camera on” policy is an entirely reasonable baseline.

Third, this “interaction enhancing” improves alertness — and probably helps students learn more.

The study’s authors are quite cautious about this claim; for technical reasons, it’s difficult to measure “learning” in this research paradigm.

But they found that increased alertness correlated with more learning. And: it certainly makes sense that students who pay attention learn more.

TL;DR

If we must teach online, we’ve got a few simple strategies to promote student alertness:

If we ask students to keep their cameras on, answer questions every now and then, and undertake retrieval practices exercises…

…they pay more attention, and probably learn more.

A Technical Footnote about Vocabulary

In the field of psychology, vocabulary can get tricky. We often have several words to describe more-or-less the same psychological concept. (E.g.: “the testing effect” and “retrieval practice.”)

This thing that I’m calling “alertness” is — in fact — often called “alertness”: so I’m not using an incorrect word. But it’s more often called “arousal”; this research team uses that word in their study.

Now, I’m a high-school teacher — so I do not like that word; as the kids say, “it squicks me out.”

So, in this blog post, I’ve preferred the word “alertness.” If you read the study its based on, you’ll see the other a-word.

Gellisch, M., Morosan-Puopolo, G., Wolf, O. T., Moser, D. A., Zaehres, H., & Brand-Saberi, B. (2023). Interactive teaching enhances students’ physiological arousal during online learning. Annals of Anatomy-Anatomischer Anzeiger, 247, 152050.

![“Rich” or “Bland”: Which Diagrams Helps Students Learn Deeply? [Reposted]](https://www.learningandthebrain.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/AdobeStock_252915030_Credit.jpg)