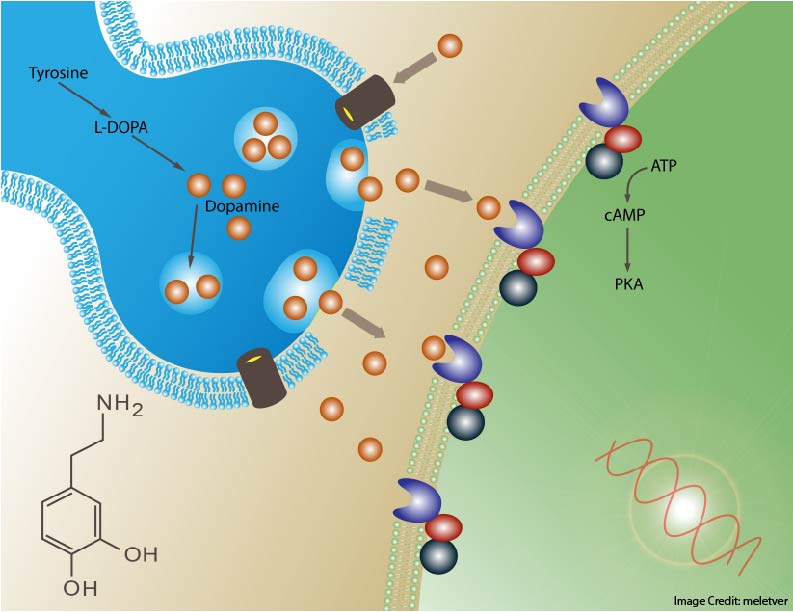

Neuroscientists talk a lot about neurotransmitters. These chemicals move from one neuron to another at synapses, and in this way help brain cells communicate with each other.

We’ve got several dozen different kinds of neurotransmitters.

Some you never hear about. When was the last time you heard about tyramine? Or, octopamine? (I really hope it has eight legs.)

Others you hear about all the time. Serotonin. Glutamate. Oxytocin.

And dopamine.

Dopamine, Motivation, and Learning

Teachers hear a lot about dopamine, because it’s an essential ingredient in neural networks central to both learning and motivation.

Of course, we care deeply about both of those topics, and so we naturally want to know more.

However, learning and motivation aren’t the same thing.

They interact, of course. I might learn something that, in turn, motivates me. Or, my general academic motivation might help me learn. But, each is possible without the other.

How, then, do we make sense of dopamine’s role in our world?

In his recent article What Does Dopamine Mean, John Burke sums up the question this way:

Dopamine is a critical modulator of both learning and motivation. This presents a problem: how can target cells know whether increased dopamine is a signal to learn or to move?

Speed Counts. Or, Not.

Often, different rates of dopamine change have been held up as explanations to answer this question.

According to this theory: slow dopamine change = motivation. Fast dopamine change = error detection and learning.

Burke, however, has a different theory:

Dopamine release related to motivation is rapidly and locally sculpted by receptors on dopamine terminals, independently from dopamine cell firing. Target neurons abruptly switch between learning and performance modes, with striatal cholinergic interneurons providing one candidate switch mechanism.

Got that? It’s all about the striatal cholinergic interneurons.

Implications for Teaching

About a year ago, I wrote this:

I encourage you to be wary when someone frames teaching advice within a simple framework about neurotransmitters. If you read teaching advice saying “your goal is to increase dopamine flow,” it’s highly likely that the person giving that advice doesn’t know enough about dopamine.

BTW: it’s possible that the author’s teaching advice is sound, and that this teaching advice will result in more dopamine. But, dopamine is a result of the teaching practice–and of a thousand other variables–but not the goal of the teaching practice. The goal of the teaching is more learning. Adding the word “dopamine” to the advice doesn’t make it any better.

In brief: if teaching advice comes to you dressed in the language of neurotransmitters, you’ll get a real dopamine rush by walking away…

Burke’s article, I believe, underlines that point. At present, scientists don’t know the answer to very basic questions about dopamine’s effect on students’ learning and motivation.

As teachers, we can be curious about dopamine and serotonin and oxytocin. But we should focus on teaching and learning…not on the dimly-understood neurotransmitters that make them possible.