Researchers can provide guidance to teachers by looking at specific teaching practices.

In last week’s post, for instance, I looked at a study about learning from mistakes. TL;DR: students learned more from review sessions where they explored their own mistakes than those where teachers reviewed ideas.

Or,

Back in December, I looked at a study about using “pre-questions” to reduce mind-wandering. Sure enough, students who answered pre-questions about a topic spent less time mind-wandering than those who didn’t.

Obviously, these studies might provide us with lots of useful guidance.

At the same time, this “one-study-at-a-time” approach has its drawbacks. For instance:

What if my students (or class) don’t really resemble the students (or class) in the study?

What if THIS study says that pre-questions reduce mind-wandering, but THAT study says they don’t?

What if THIS study (again) says that pre-questions reduce mind wandering, but THAT study says that mindful meditation reduces mind-wandering? Which strategy should I use?

And so forth.

Because of these complexities, we can — and should — rely on researchers in another way. In addition to all that research, they might also provide conceptual frameworks that help us think through a teaching situation.

These conceptual frameworks don’t necessarily say “do this.” Instead, they say “consider these factors as you decide what to do.”

Because such guidance is both less specific and more flexible, it might be either especially frustrating or especially useful.

Here’s a recent example…

Setting Goals, and Failing…

We spend a lot of time — I mean, a LOT of time — talking about the benefits of short-term failure. Whether the focus is “desirable difficulty” or “productive struggle” or “a culture of error,” we talk as if failure were the best idea since banning smoking on airplanes.

Of course, ask any student about “failure” and you’ll get a different answer. Heck: they might prefer smoking on airplanes.

After all: failure feels really unpleasent — neither desirable nor productive, nor cultured.

In a recent paper, scholars Ryan Carlson and Ayelet Fishbach explore the complexity of “learning from failure”: specifically, how failure interefers with students’ goals.

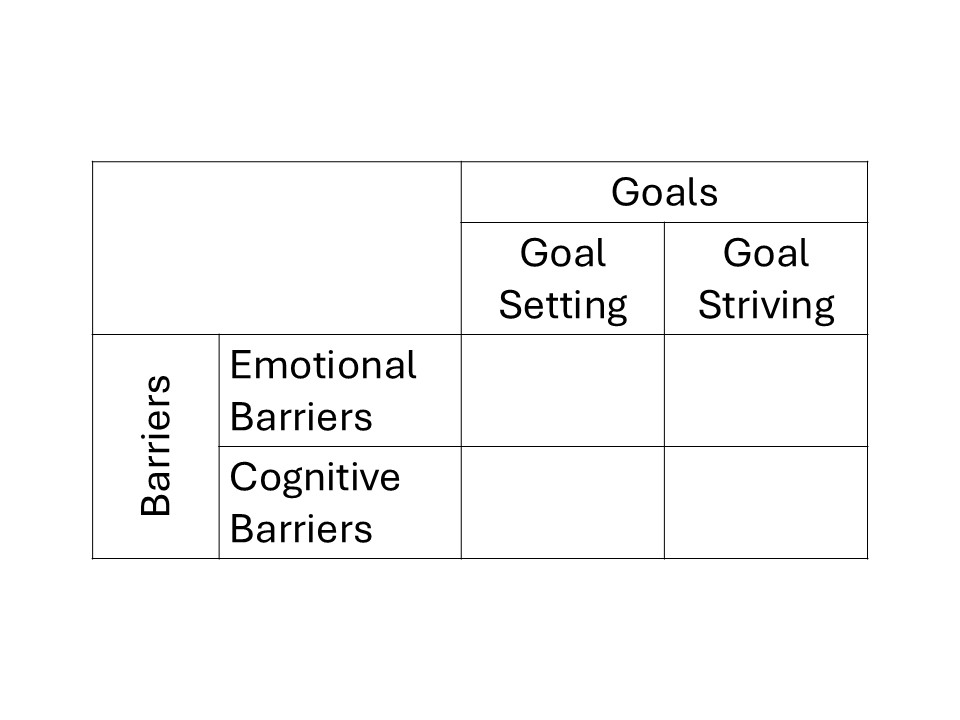

To create a conceptual framework around this question, Carlson and Fishbach create two concept pairs.

First: they consider the important distinction between goal setting and goal striving.

Happily, those terms mean just what they say.

When I decide that I want to learn Spanish, or strengthen my friendships, or stop drinking caffein, I am setting a goal.

When I decide to enroll in a Spanish class, schedule more frequent dinners with pals, or purge my kitchen of all my coffee clutter, now I’m goal striving.

This pair helps us think through the big category “goals” in smaller steps.

Second: Carlson and Fishbach consider that both emotional barriers and cognitive barriers can interfere with goal setting and goal striving.

The resulting conceptual possibilities look like this:

The grid created by these conceptual pairs allows us to THINK differently about failure: both about the problems that students face, and the solutions that we might use to address them.

Troubling Examples

Having proposed this grid, Carlson and Fishbach explore research into its four quadrants. I’ll be honest, resulting research and insights frequently alarmed me.

For instance, let’s look at the top-left quadrant: “emotional barriers during goal setting.”

Imagine that one of my students contemplates an upcoming capstone project. She wants to set an ambitious goal, but fears that this ambitious target will lead to failure.

Her emotional response during goal setting might prompt her to settle for an easier project instead.

In this case, her emotional response shuts down her thinking before it even started. As Carlson and Fishbach pithily summarize this situation: “people do not need to fail for failure to undermine learning.”

YIKES. (Suddenly, the whole “desirable difficulties” project sounds much less plausible…)

Or, top right (emotional barriers/goal striving): it turns out that “information avoidance” is a thing.

People often don’t want to learn results of medical tests — their emotions keep them from getting to work solving a potential health problem.

So, too, I can tell you from painful experience that students often don’t read the comments on their papers. When they’re disappointed with a grade, they don’t consistently react by considering the very feedback that would help them improve — that is, “strive to meet the goal of higher grades.”

Or, lower right (cognitive barriers/goal striving). Carlson and Fishbach describe a study — intriguingly called “The Mystery Box Game.”

Long-story short: in this game, learning how to fail is more beneficial than learning about one path to success. Yet about 1/3 of participants regularly choose the less beneficial path — presumably because “learning how to fail” feels too alarming.

Problems Beget Solutions?

So far, this blog post might feel rather glum: so much focus on failure!

Yet Carlson and Fishbach conclude their essay by contemplating solutions. Specifically, they use a version of that grid above to consider solutions to the cognitive and emotional barriers during goal setting and goal striving.

For example:

- “Vicarious learning”: people learn more from negative feedback when it’s directed at someone else.

- “Giving advice”: counter-intuitively, people who give advice benefit from it at least as much as those who receive it. So, students struggling with the phases above (say: cognitive barriers during goal striving) might be asked for advice on how to help another student in a similar situation. The advice they give will help them.

- “Counter-factual thinking”: students who ask “what if” questions (“what if I had studied with a partner? what if I had done more practice problems”) bounce back from negative feedback more quickly and process it more productively.

Because I’ve only recently come across this article, I’m still pondering its helpfulness in thinking about all these questions.

Given the optimism of “desirable difficulty/productive struggle” in our Learning and the Brain conversations, I think it offers a helpful balance to understand and manage these extra levels of realism.

Carlson, R. W., & Fishbach, A. (2024). Learning from failure. Motivation Science.