The US Department of Education recently released a video on eX/Twitter encouraging the use of “squishy toys” to calm students. In the video, an earnest school psychologist says that such toys help his students focus without distracting others.

The uproar that followed — “they’re vital!” vs. “they’re dreadful” — followed the usual eX/Twitter pattern.

Of course, here on this blog we’re interested in narrower questions than “are squishy toys good or bad?” We want to know:

- do we have a consistent body of research giving us useful guidance on using squishy toys in K-12 classrooms?

- if they have benefits, what are the boundary conditions? That is: perhaps they help some students but not others?

- what kind of benefits are we talking about here? At a minimum, I think we want students to focus better and learn more. In other words: if the benefit is “students like ’em,” that’s not a good enough reason to consider squishy toys a research-supported classroom tool.

So, what happens when we start investigating those questions?

The Home Team Looks Worried

When people offer teachers “research-based” advice, we’d like them to cite the research. That’s both common courtesy and common sense.

Sadly, the video itself — and the tweet that contains it — doesn’t provide a citation or link to any research. The school psychologist, as far as I can tell, is making an experienced-based claim, not a research-based claim.

Of course, teachers and school leaders rely on experience all the time, so this approach isn’t obviously ridiculous. At the same time, given that we can research a question like this, it’s surprising that the initial advice doesn’t take advantage of the research that is (almost certainly) out there.

So, what happens when we go looking for the research supporting the use of squishy toys?

Let’s imagine the following conversation:

ANDREW: You should take this medecine; research says so.

YOU: Tell me about this research.

ANDREW: It was done by a doctor who bleeds his patients to cure their fevers.

YOU: Wait…he bleeds his patients? That’s medical malpractice…it’s been out-of-date for decades, even centuries!

ANDREW: So what’s your point?

At this point, I suspect, you’d stop taking my medical advice.

When I asked Elicit.com to find research about using squishy toys in K-12 classrooms, the only relevant study it located notes that:

“Kinesthetic learners used the stress balls more consistently and their attention spans increased more when compared to other learners.”

This observation would be interesting if “kinesthetic learners” existed, and if we haven’t known for decades that learning styles theory isn’t supported by evidence. At a mimimum, we shouldn’t trust this study’s conclusions that squishy toys benefitted students.

To be clear, the study includes other key limitations:

- It’s a self-described pilot study, including 29 students.

- It mostly measures self-reported variables — not an especially persuasive foundation for teaching advice.

It’s not looking good for Team Squishy.

Don’t Stop Yet

I’ve tried two steps to verify the squishy-toy claim:

- Check with the person who made the recommendation.

- Look on Elicit.com.

Although those attempts didn’t pan out, we’ve still got several other avenues to pursue.

I checked with Scite.ai; it couldn’t even find that kinesthetes-love-squishy-toys study. (It’s REALLY rare for Scite.ai to come up short this way.)

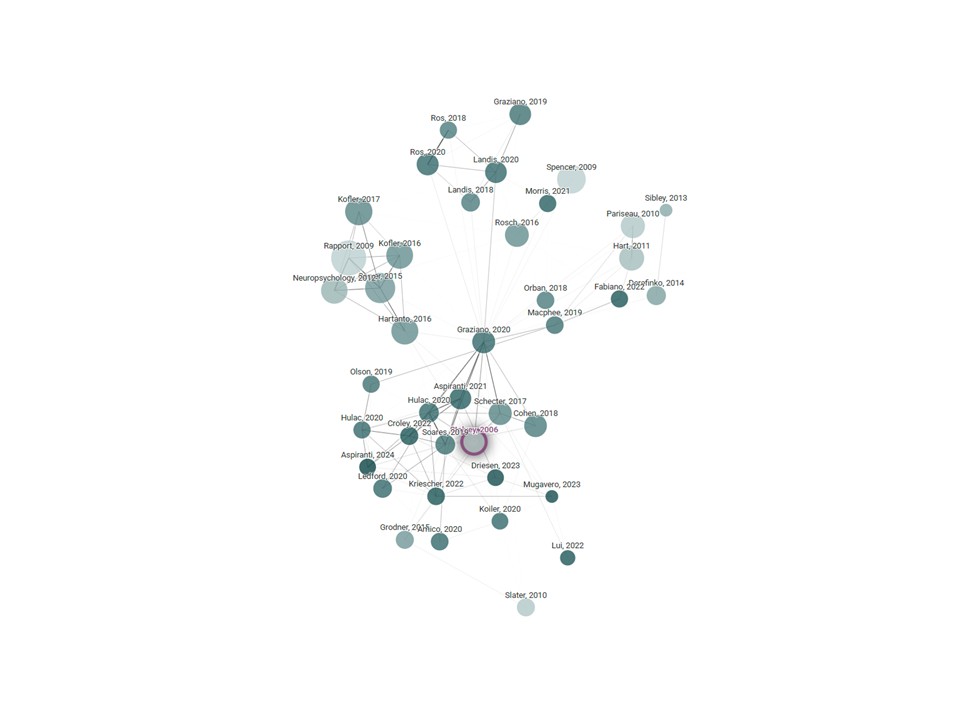

I next went to ConnectedPapers.com to look for other studies surrounding that study; here’s the image it generated. (The study I started with is in the purple circle.)

So, I started poking around at the studies surrounding the first one. Of course, I didn’t look at them all — life is short. But, here’s what I found with some random checks:

- “Fidget spinners negatively influence young children with ADHD’s attentional functioning, even in the context of an evidence-based classroom intervention.” (This from the Graziano study right in the middle.) 1

- “Due to a recent surge in popularity, fidget spinners and other self-regulatory occupational therapy toys have yet to be subjected to rigorous scientific research. Thus, their alleged benefits remain scientifically unfounded. Paediatricians should be aware of potential choking hazards with this new fad, and inform parents that peer-reviewed studies do not support the beneficial claims.” 2

- “Student performance was lower when they were allowed to use fidget spinners than when the fidget spinner was removed. The current study suggests that fidget spinners may cause a deficit in student performance. However, the effect of fidget spinners may actually lessen as the students habituate to the objects.” 3

- “Using a fidget spinner was associated with increased reports of attentional lapses, diminished judgments of learning, and impaired performance on a memory test for the material covered in the video. The adverse effect on learning was observed regardless of whether the use of fidget spinners was manipulated between‐subjects (Experiment 1) or within‐subjects (Experiment 2), and was observed even when the sample and analysis were limited to participants who came into the study with neutral or positive views on the use of fidget spinners.” 4

I could go on. From this quick investigation, I notice two important patterns.

First:

No one seems to be researching stress balls (a.k.a. “squishy toys”) at all. The ONLY study I found on that topic is the pilot study with the kinesthetic learners.

Second:

Scholars ARE studying fidget spinners … and not finding any good news. Whether you’re teaching K-12 students or college students, neurotypical students or students with ADHD, kinesthetic learners or students who really exist: none of them receives classroom benefits from a fidget spinner.

Third:

To be on the safe side, I looked for meta-analyses — both ones that focus on squishy toys, and ones focusing on fidget spinners.

Unsurprisingly, I didn’t find ANY looking at squishy toys. And — equally unsurprisingly — I the fidget-toy meta-analyses sounded consistently discouraging notes. (For example, this one.)

My Current Conclusion

When I do this kind of research deep dive, I usually find conflicting evidence. As a result, I typically write a tentative, partly-yes and partly-no summary: “strategy X seems to work well with these students studying these things, but we don’t have good research outside that small group.” Or something like that.

In this unusual case, the research picture seems unambiguous to me:

- We have NO reliable research showing that squishy toys benefit (or harm) students.

- We have LOTS of research showing that fidget spinners provide few benefits, and can indeed interfere with learning.

If you have research that contradicts these conclusions, please let me know.

- Graziano, P. A., Garcia, A. M., & Landis, T. D. (2020). To fidget or not to fidget, that is the question: A systematic classroom evaluation of fidget spinners among young children with ADHD. Journal of attention disorders, 24(1), 163-171. ↩︎

- Schecter, R. A., Shah, J., Fruitman, K., & Milanaik, R. L. (2017). Fidget spinners: Purported benefits, adverse effects and accepted alternatives. Current opinion in pediatrics, 29(5), 616-618. ↩︎

- Hulac, D. M., Aspiranti, K., Kriescher, S., Briesch, A. M., & Athanasiou, M. (2021). A multisite study of the effect of fidget spinners on academic performance. Contemporary School Psychology, 25, 582-588. ↩︎

- Soares, J. S., & Storm, B. C. (2020). Putting a negative spin on it: Using a fidget spinner can impair memory for a video lecture. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34(1), 277-284. ↩︎