Those of us who study the intersection of research and teaching can get carried away all to easily.

After all: psychology research can provide enormous benefits to teachers and school leaders. More important, it benefits the students and families who depend on us. Because this reseach can help us understand — say — memory and attention, it can improve the way we teach and think about almost every school-keeping topic.

No wonder we get so excited. “Here’s the research!” we cry. “Now, go use it wisely!”

Of course, the gap between “having the research” and “using it wisely” is…ENORMOUS. If we understand research correctly, it can indeed help us know what to do. But…

… what if we’re relying on flawed research? or

… what if we’re using research that doesn’t apply to the biggest problem in our school? or

… what if we incorporate the research in our thinking, but don’t have a clear system to evaluate its effects, or…

This list goes on.

Those of us who want psychology and neuroscience research to improve education need a better system for “using research wisely” in schools.

Today’s News: Towards a Better System

I’ve been thinking about the broader difficulties of “using research wisely in education” because of a recent book: Evidence-Informed Wisdom: Making Better Decisions in Education. The authors — Bradley Busch, Edward Watson, and Matthew Shaw — see exactly this problem, and have lots of guidance to offer.*

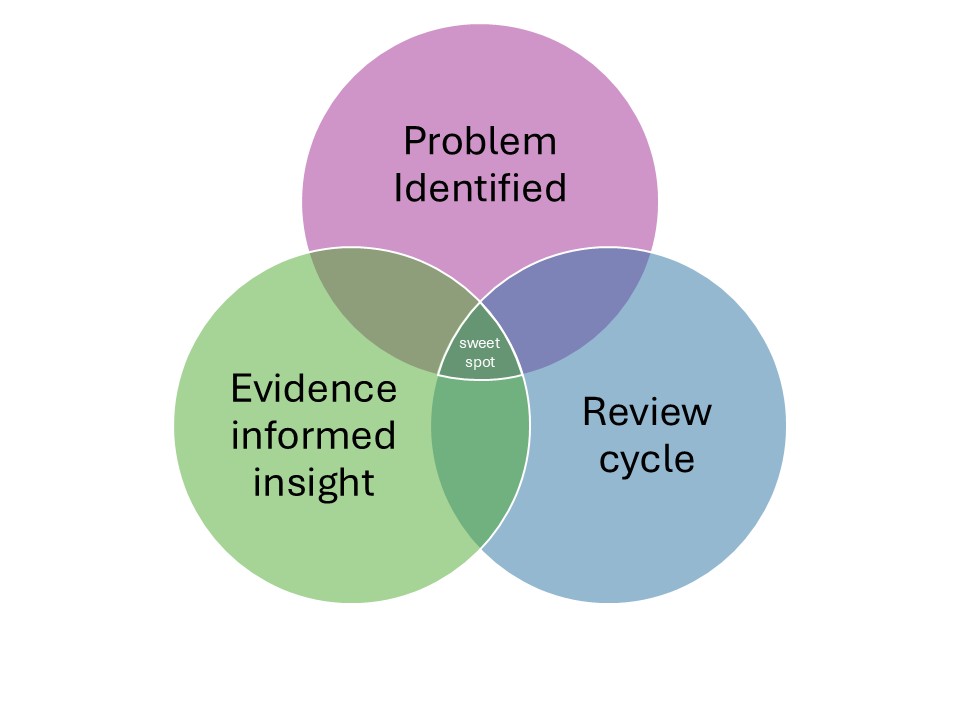

This book includes several quotations and charts and anecdotes worth savoring; I want to focus on a Venn diagram that has really got methinking. Here’s an incomplete version:

As you can see, Busch, Watson and Shaw argue that we can find the “sweet spot” when we undertake three complex processes simultaneously.

- In the first place, we need to identify the problem correctly.

- Second, we should have a plan that relies on evidence and research.

- And third, we need to monitor that plan.

Of course, each circle in this Venn diagram requires lengthy exploration. I myself have written a book about evaluating the “evidence” which we might use in the green circle. And Evidence-Informed Wisdom takes several pages to explore the “review cycle” in the blue circle: an idea drawn from Bruce Robertson’s work.

But the core insight here is: while each of these processes merits its own book, we get the most powerful effect from doing all three at the same time.

Mind the Gaps

Venn diagrams help us think because they label the places that circles overlap. Those labels typically emphasize the commonalities that the circles share.

For instance, a humorous Venn diagram considers “bank robbers” and “night club DJs.” Their commonality: “people who tell you to put your hands in the air.”

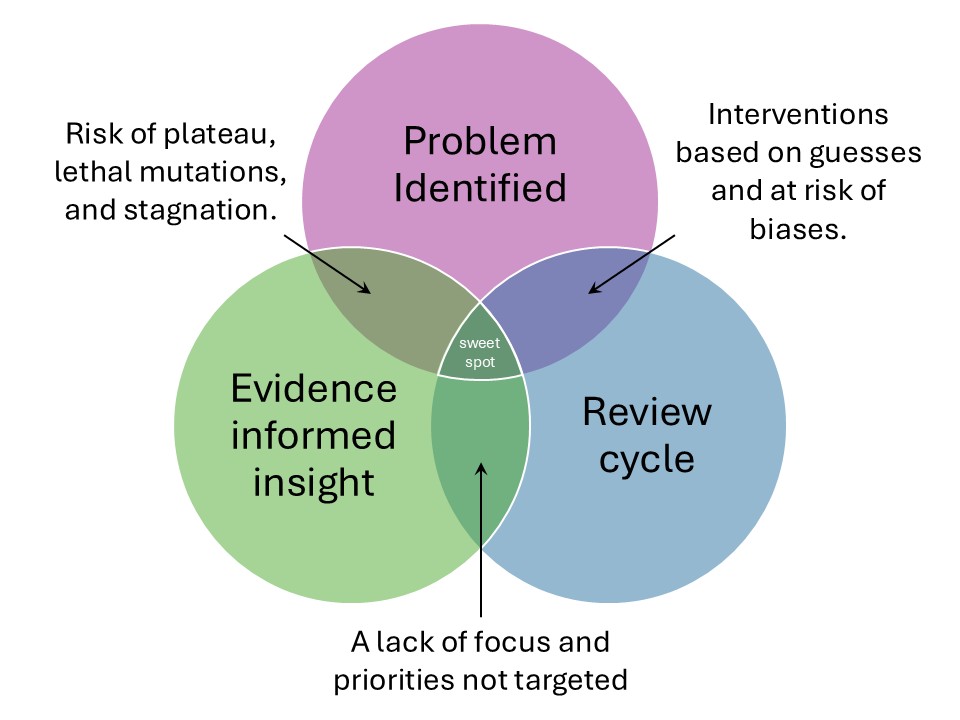

Busch, Watson, and Shaw have a different approach to that overlap. Check out this more-complete version (from page 80 of their book):

Notice that in this Venn diagram, the labels do NOT highlight the commonality between the two circles. Instead, they name the specific problems created by the absence of the third circle.

So: if I successfully identify the problem (the purple circle) and use evidence to plan a solution (the green circle), I’m wisely accomplishing two key processes. For that reason, I might make meaningful progress for a while.

However — and this is a BIG however — I’ve skipped out on Robertson’s review cycle (the blue circle). Without that additional process, my initiative might…

- …lose focus. For example: my colleagues and I might all think we’re using retrieval practice…but we’re not all using it consistently and well.

- …lose momentum. We could start out strong, but easily get distracted by the next shiny new thing. (I’m looking at you, AI.)

Or, if our school runs a scrupulous process to identify our most pressing problem and develop a clear “try-review-reflect” cycle, our good work might well help our students.

HOWEVER, because we didn’t use research to inform our decision making, we might be trying, reviewing, and reflecting upon a foolish plan.

In other words: this Venn diagram reminds us of three essential processes to keep in mind. And, it highlights the symptoms we’ll see and feel if we skimp on one of those processes.

As a bonus, it also offers a fun new way to think about creating Venn diagrams.

TL;DR

- We absolutely should use research to inform our teaching and our school keeping.

- The process of “using research” isn’t straightforward; it requires at least three complex processes used in a just and nuanced balance.

- Busch, Watson, and Shaw have created a really helpful way to think simultaneously about all three.

When you and your school decide to follow the evidence-informed path, this diagram will guide your exploration.

* Two important notes:

- As far as I know, I’m not related to Edward Watson.

- I have a policy that I don’t review books written by friends. For that reason, I’m not reviewing this book. I am, instead, writing about a topic that it explores.