I’ve been honored over the years to meet so many of you who read this blog, and who think aloud with me about its topics. (If you see me at a Learning and the Brain conference, I hope you’ll introduce yourself!)

And, I thoroughly enjoyed the opportunities I’ve had to chat with researchers and other scholars as I try to understand their arguments.

As I look back over these years, some emerging themes stand out to me:

A Man, a Plan

When I attended my first Learning and the Brain conference in 2008, I knew what was going to happen:

Step 1: the “brain researchers” would tell me what to do.

Step 2: I would do it.

I would, thus, be practicing “brain-based teaching.” My students would learn SO MUCH MORE than they had in the past.

How hard could it be to follow researchers’ instructions? It turns out: it’s extremely hard simply to “follow researchers’ instructions.”

In the years since that conference, I’ve realized — over and over — how little I knew about what I didn’t know.

Surprise #1: One Size Does Not Fit

The first problem with my 2-step plan: I almost certainly SHOULDN’T DO what the researchers did.

Why?

Let’s say researchers studying the spacing effect asked college students to study three math topics.

Those students did five practice problems once a week for five weeks.

Voila: those students learned more than students who just did all 25 problems at once.

So, I should have my students do five practice problems once a week for five weeks, right?

Hmmm.

I’m a high school teacher. I teach English. I might not teach only three topics at a time. I might have more than 25 practice problems.

So, I can’t simply use the researchers’ formula for my own teaching plan.

Instead of doing what the researchers did, I should think the way the researchers thought.

The researchers’ successes resulted — in part — from the goodness of fit between their method, their students, and their topic.

To get those same successes in my classroom, I have to adapt their ideas to my particular context.

And: all teachers have to do exactly that kind of adapting.

In Step 2 above, I can’t just do what the researchers did. I always have to tailor their work to my teaching world.

Surprise #2: People Are COMPLICATED

Back in 2008, I assumed that “brain-research” would consistently show the same correct answers.

If I knew a correct answer, I could simply do the correct thing.

Alas, it turns out that research studies doesn’t always arrive at the same answer — because PEOPLE ARE COMPLICATED.

So: is focusing on Growth Mindset a good idea?

Although Mindset Theory has been VERY popular, it also generates lots of controversy.

Should schools require mindful meditation?

How much classroom decoration is too much?

If you look at the comments on this post, you’ll see that many teachers REALLY don’t like research-based answers to that question.

In other words, I can’t just “do what the research tells me to do,” because research itself comes up with contradictory (and unpopular) answers.

Surprise Research #3: “Brain Research” Isn’t (Exactly) One Thing

Throughout this post, I’ve been putting the words “brain research” in quotation marks.

Why?

Well, I was surprised to discover that researchers study the “brain” in at least two different ways.

If you really like biology, and want to study the “brain” as a physical object, you’ll go into a field called “neuroscience.”

You’ll look at neurons and neurotransmitters and glial cells and fMRI and EEF and myelination and the nucleus accumbens.

You’ll look at cells under microscopes, and prod them with pointy things while wearing gloves.

BUT

If you really like thoughts and emotions, and want to study the “brain” according to its mental processes, you’ll go into a field called “psychology.”

You’ll look at attention and memory and stress and learning and perception.

Notice: psychologists don’t look at attention under a (literal) microscope. They can’t pick up “stress” the way they can pick up a brain or an amygdala. They don’t need to wear gloves. Nothing damply biological is happening.

Yes, these days these neuroscience and psychology are blurring together. We have people interested in “neuro-psychology”: the biological underpinnings of all those mental processes — memory, curiosity, generosity.

But that blurring is very recent — a couple of decades at most.

And most people in those fields don’t blur. They stick to one team or the other. (For most of the 20th century, these two fields eyed each other with disapproval and suspicion.)

Surprise #4: Psychology First

I don’t like the sentences I’m about to type, but I do think they’re true.

Back in 2008, when I first got into this field, I was REALLY interested in the neuroscience.

The very first question I asked at a Learning and the Brain conference was “where does attention happen in the brain?”

But, the more time I spend in this field, the more I think that teachers need information from psychology more than from neuroscience.

Yes, the neuro is fascinating. But, it almost never helps me teach better.

For instance:

I don’t need to know where long-term memories are stored in the physical brain. (That’s a question that neuroscientists try to answer.)

I do need to know what teaching strategies help students form new long-term memories. (That’s a question that psychologists try to answer.)

I focus on this topic — the relative importance of psychology for teachers — because so many people use neuroscience to boss teachers around.

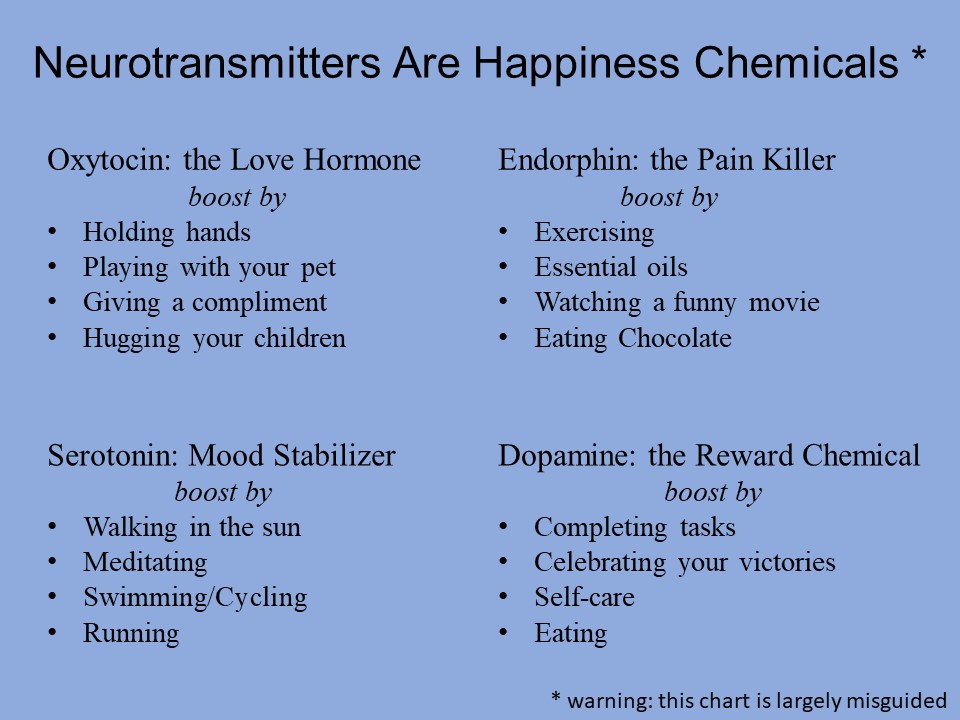

Heck, I recently wrote a post about the bizarre claim that “neurotransmitters are happiness chemicals“: a claim that uses neuroscience to tell teachers what to do.

I myself think that anyone who wants to tell teachers “do this new thing!” should have tested that new thing directly with students. We call that research “psychology.”

TL;DR

Here’s what I would tell my 2008 self:

“This field you’re entering will help you and your students SO MUCH!

And, you should know:

You’ll always be translating research findings to your own classroom.

Because researchers and teachers disagree, you’ll always sort through controversy before you know what to do.

Neuroscience research is fascinating (fMRI is SO COOL), but psychology research will provide specific and practical suggestions to improve your teaching and help your students learn.”

I hope this blog has helped make some of those ideas clear and interesting over the years. And: I’m looking forward to exploring them with you even more…