This guest review of Blake Harvard’s Do I Have Your Attention is written by Justin Cerenzia.

Having followed Blake Harvard’s “The Effortful Educator” blog from its very beginning, it feels especially fitting that his new book – Do I Have Your Attention? Understanding Memory Constraints and Maximizing Learning – poses a question many of us have enthusiastically answered “yes” to for nearly a decade.

Yet this book represents more than an extension of Harvard’s blog—it marks the culmination of his long-standing influence as a leading educator: one who connects cognitive science with classroom practice. Thoughtfully structured into two complementary sections, the book skillfully integrates theoretical perspectives on how memory functions with actionable classroom strategies, offering educators practical tools to foster meaningful and lasting learning.

Harvard deftly navigates the complexities often inherent in cognitive science research. His writing style is both approachable and authoritative, resonating equally with newcomers and seasoned readers alike.

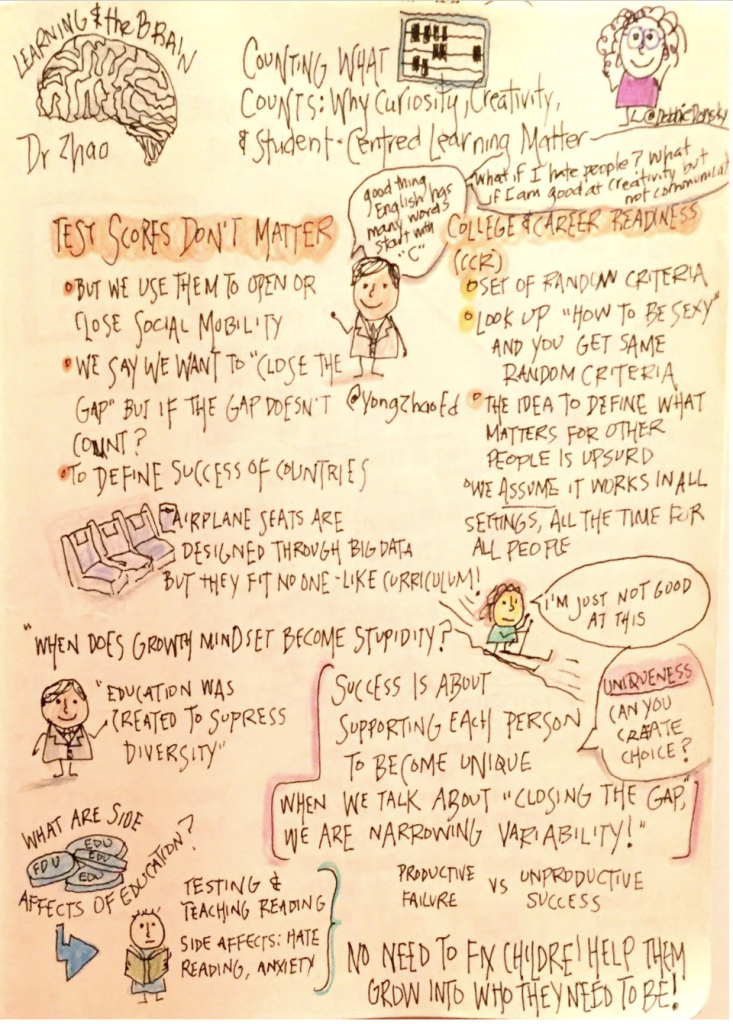

Much of Part I leverages Professor Stephen Chew’s An Advance Organizer for Student Learning: Choke Points and Pitfalls in Studying. Harvard uses this foundational framework to clarify key concepts and common misunderstandings about memory and learning. Crucially, Harvard’s position as a classroom teacher lends him credibility and authenticity, grounding his insights firmly in practical experience rather than mere theory.

It’s as though we’re invited into Blake’s classroom, watching him expertly guide us through Chew’s graphic.

And this is precisely how he frames the opening of Part II, writing:

“It can be quite overwhelming to know just what is the best bet for optimizing working memory without overloading it while also making the most of moving the content to long-term memory. Compound that with the fact we are tasked with educating, not one brain, but a classroom full of them. That’s a job that only a teacher can understand and appreciate” (65).

Harvard then succinctly-yet-thoroughly guides readers through seven carefully considered strategies to maximize learning. In each case, he showcases a diverse array of tactics that enrich any skilled teacher’s toolkit—all with the ultimate goal of positively influencing student outcomes.

Throughout, he pulls back the curtain even further, transparently revealing how specific shifts in his own teaching practice improved student learning. Clearly, each change has been guided by careful investigation and thoughtful application of research.

That Harvard’s insights—long influential in the educational blogosphere—are now available in book form represents a win for educators everywhere. Rich in research yet highly accessible, this text serves as both an inviting entry point and a resource for deeper exploration.

So too does it underscore the essential role teachers can and should play alongside the research community, brokering knowledge and further bridging the unnecessary divide that sometimes impedes meaningful change. In an era rife with educational theory, Harvard’s concrete examples of classroom success help ensure that even hesitant educators find meaningful, practical guidance.

If Blake Harvard didn’t already have your attention, you’d do well to give it to him now.

If you’d like to learn more, Blake’s webinar on attention and memory will be May 4.

Justin Cerenzia is the Buckley Executive Director of Episcopal Academy’s Center for Teaching and Learning. A Philadelphia area native, Justin is a veteran of three independent schools over the last two decades, dedicating his career to advancing educational excellence and innovation. A history teacher by trade, Justin nonetheless considers the future of education to be a central focus of his work. At Episcopal Academy, he leads initiatives that blend cognitive science, human connection, and an experimenter’s mindset to enhance teaching and learning. With a passion for fostering curious enthusiasm and pragmatic optimism, Justin strives to make the Center a beacon of learning for educators both within and beyond the school.