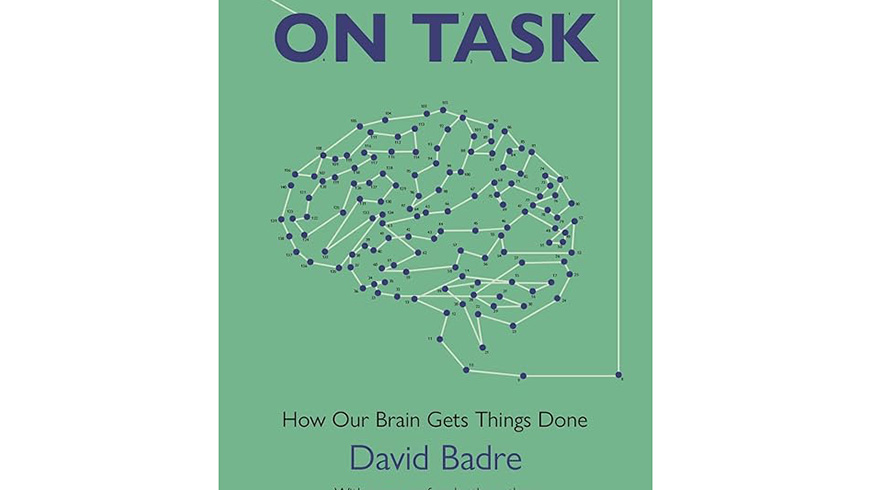

I’ve been staring at my to grade pile—essays, exams, books I’ve been meaning to read, skills I want to develop—and honestly, it’s not that I don’t want to begin. I just… can’t. I open a document, then blink, and suddenly it’s dinner time. I’ve read all the Getting Things Done books, but what is it that gets me On Task when I already know what to do? Sound like a familiar question? That tension between desire and initiation is exactly at the heart of David Badre’s On Task: How Our Brain Gets Things Done.

Badre, a cognitive neuroscientist, invites us into that murky space between knowing and doing. He shows how our brains—particularly the prefrontal cortex—juggle goals nested inside other goals (make coffee, generate a lesson plan, grade essays), and why that juggling sometimes comes crashing down. He doesn’t promise a self‑help checklist; instead, he offers compassionate clarity: our executive function is powerful and fragile, built for hierarchies, stability‑vs‑flexibility trade‑offs, and moment‑to‑moment cost‑benefit calculations. Badre is willing to wade into the philosophical and biological depths of what it means to have a mind at all.

Throughout the book, Badre asks: are we really steering our lives, or are we just riding the rails of our biology and past conditioning? When my students and I discuss biopsychology or epigenetics, we circle the same tension: with so much shaped by brain circuitry, classical conditioning, even the hidden influence of our genes and society—what does it mean to choose? Badre is honest about these boundaries. He uses case studies—like patients who, after prefrontal brain injury, can explain their intentions but can’t act on them—to explore the razor-thin margin where knowledge ends and true agency might begin. He draws on neuropsychological history, from Penfield’s sister to the famous EVR, and roots these questions in the living, vulnerable architecture of the brain.

You will get a strong foundation along with these great stories: Badre digs into computational models and the messy, ongoing debates about how cognitive control is organized. He walks us through the brain’s hierarchies—how the prefrontal cortex can set broad, abstract goals and then decompose them into practical action—and then pulls back to ask what these models do (and don’t) explain about everyday life. You get stability and flexibility, multitasking, inhibition and switching, the information retrieval problem, the limits and benefits of control across the lifespan. Some readers call the book demanding or dense in spots, but that’s part of the payoff: Badre trusts us to join the scientific conversation, not just spectate. And even just getting the gist of tough parts will change your thinking.

In my daily life, all this plays out like driving home on autopilot—forgetting the road, feeling the inertia of routine, and ending up somewhere unintended. In classrooms, I see students wrestling with the same forces: between conditioned knowledge of what to do, procrastination, and action. In pandemic classrooms and the distractions of current politics, we all feel a deficit in our cognitive systems—our routines unravel, our attention frays, and our brains realize how much effort it takes to get On Task when the scaffolding disappears. If you’ve ever wondered why a simple act like making coffee can feel so complicated—or what happens in a brain when you try to stop one task and start another—this book offers insight, not just explanation.

What stays with me is that Badre refuses false optimism. He doesn’t say, “just build more willpower.” Instead, he hands us a mirror: our executive function is shaped—and we can shape it too, through environment, practice, small routines. That kind of insight feels hopeful because it’s real. It demands curiosity, not quick fixes.

So here’s my punch at the end, inspired by his closing: On Task feels less like a how‑to‑guide and more like an invitation—to observe our own hidden machinery, to notice how easily routine can slide into unawareness, and to ask: Who am I when my executive function is truly steering? What small moments—making coffee, grading papers, reading a chapter—might I reclaim to bring more awareness, more agency, more grounded action?

If your familiar with “I know what I should do, but I just can’t!”—this is a book to read. It doesn’t diagnose you. It doesn’t sell you magic. It helps you see the space where your choices live—and getting to know me, feels like a foundation worth building on.