I spend my days giving research-informed advice to teachers and school leaders. You could summarize my pitch this way:

According to my current best understanding, we’ve got some good research suggesting that X strategy is likely to help most students learn most things.

Sometimes I say:

We’ve got LOTS of research suggesting…

Or occasionally:

We’ve got a few encouraging studies that make me think…

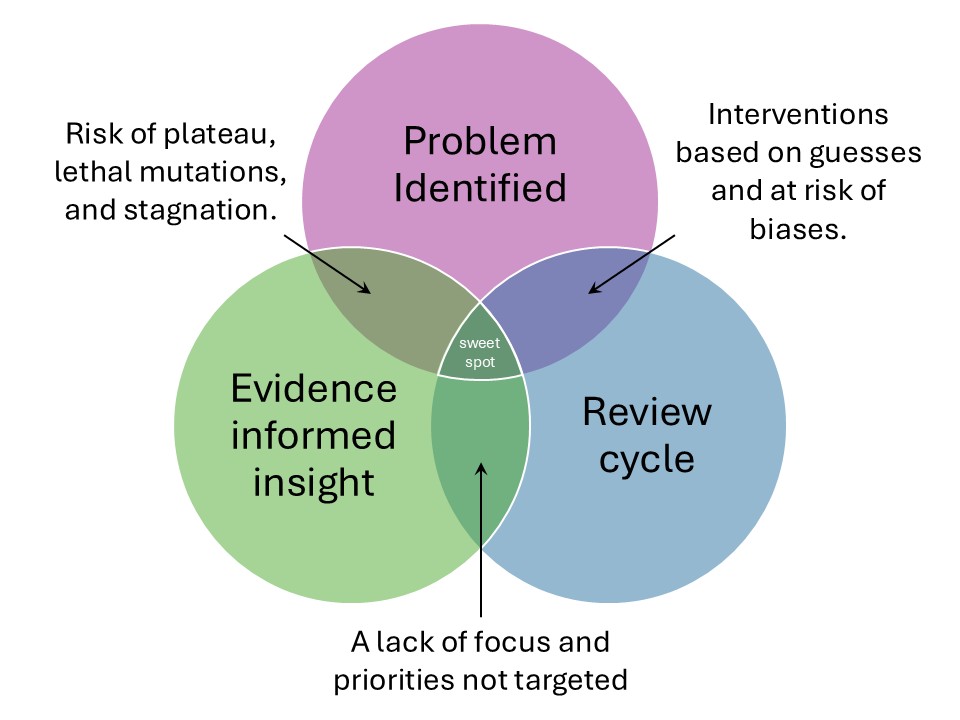

In every case, these research-informed suggestions arise from the CURRENT state of the research.

Of course, researchers haven’t stopped working…they’ve only just begun. Hundreds (thousands?) of graduate students and professors are out there right now. They’re exploring:

- working-memory limitations, and

- the benefits of mindfulness, and

- the relationship between handwriting fluency and reading comprehension

And SO MANY other topics.

For this reason the advice that I gave yesterday based on “the current state of the research” could be contradicted by today’s research. My job isn’t just to find “what the research has said,” but to keep track of the ongoing conversation that current researchers have with prior conclusions.

In other words: “research-informed” teaching advice evolves over time. Occasionally, I have to retract advice I’ve given in the past.

Prior Conclusions: An Example

I’ve spent the last week talking with teachers from across the country about — among other topics — working-memory limitations, and ways to work around them.

One sensible approach: because stress hampers working memory-function, we can support working memory by reducing stress. Happily, we’ve got a few research-supported strategies for doing so.

I first heard about one strategy at a Learning and the Brain conference many years ago. Researcher Sian Beilock — currently the President of Dartmouth College! — teamed up with Gerardo Ramirez to test a surprising hypothesis. The title of their study says it all: “Writing About Testing Worries Boosts Exam Performance in the Classroom.”

Although the idea sounds counter-intuitive — in fact, both researchers were skeptical of the hypothesis — they found that letting students VENT their stress in writing dissipated the stress. More specifically, students given time to write about their anxiety about an upcoming exam did better on that exam than students who wrote about something else.

When I heard Dr. Beilock’s talk, the suggestion struck me as SO PRACTICAL. It doesn’t take much time. It helps anxious students without harming other students. It cost $0. What’s not to love?

Happily, we don’t have to rely on one study. More recently, DiMenichi and colleagues tried a similar strategy — and got similar results.

For that reason, I’ve been giving this advice for several years now: “we’ve got some good studies suggesting that letting students VENT their stress actually helps them dissipate their stress. The result: they do better on various academic measures.”

Today’s News: It’s Time for a Retraction

Recently, as I was preparing for an upcoming presentation, I looked again at my slide about the Beilock and DiMenichi studies. I realized that I hadn’t kicked those tires in a while, and I thought it would be helpful to go back and see what more researchers have found in this field.

Who knows: perhaps someone had recently done helpful study that offers creative new approach to this counter-intuitive suggestion.

I have several different strategies to evaluate research based claims: you can find a quick guide here.

Recently I’ve been using Claude to jumpstart my searches. I asked it to do a research deep dive on this question: here’s the first paragraph of its answer:

The evidence for helping students manage stress through “venting” shows a complex picture with both promising findings and significant contradictory results.

While foundational studies by Ramirez & Beilock (2011) and DiMenichi et al. (2018) demonstrated large effects for brief expressive writing interventions, subsequent research reveals substantial methodological concerns, replication failures, and evidence that such interventions can be harmful for certain students.

Meta-analyses consistently show only small effect sizes, and the majority of studies with healthy college students find no significant benefits

Now, I didn’t stop here. I looked over this review — and then explored several of those studies on my own. (As always, I relied a lot on ConnectedPapers.com and Elicit.com.) Especially because I’m new to Claude, I didn’t simply accept its guidance without question.

But — sure enough: as I see the CURRENT research picture, we don’t have a consistent and persuasive pool of studies suggesting that students benefit from venting their stress.

Pointing Fingers

If we got a wrong answer, presumably someone is at fault. So: who is it? At whom should I point when I cry j’accuse?

- Should we blame Ramirez and Beilock, for leading us astray with that initial study?

- Should we blame DiMenichi for confirming their error?

- Should we blame ME for spreading erroneous information?

I think the correct answer is: D) none of the above.

This turn of events is an entirely predictable possibility in the world of research-informed teaching advice.

- Ramirez and Beilock didn’t do anything wrong. They had a hypothesis. They tested it. They reported their results. That’s what they’re supposed to do.

- DiMenichi didn’t do anything wrong. She followed up that initial study. She reported her results. That’s what she’s supposed to do.

- I (probably) didn’t do anything wrong. I saw interesting and well-designed studies. The results aligned with each other, and with my teaching experience. I told teachers about these studies. That’s what I’m supposed to do.

- (I might have made this mistake: I might not have emphasized enough that the advice was based on a small number of studies — and therefore tentative.)

Those of us who base teaching advice on research should always acknowledge that some of our conclusions will be contradicted by future research. Occasionally, that kind of reversal just happens.

In fact: we can have confidence in research-based suggestions BECAUSE the research cycle will probably reveal false leads sooner or later. It’s not a perfect system. But as long as we stay realistic about its limitations, science can be self-correcting.

What This Means for You

First: when you get “research-based” teaching advice, ask how much research supports the claim. You don’t have to reject ideas with only a little research beind them — especially if the conclusions match your experience, or your school’s philosophy. But: be sure to check back in every now and then to see what subsequent research has found.

Second: although we can be sad that “expressive writing” probably isn’t a good strategy for helping students manage stress, we do have other strategies that can help. I’ll write about “cognitive reframing” in a future post…

Ramirez, G., & Beilock, S. L. (2011). Writing about testing worries boosts exam performance in the classroom. science, 331(6014), 211-213.