I disagree with the title of this blog post. I believe students CAN improve at taking notes. This post is my attempt to convince you that they can, and that we teachers can help them.

Over the years, I’ve written about the Laptop-Notes vs. Handwritten-Notes Debate several times.

I’ve tried to persuade readers that although people really like the idea that handwritten notes are superior, the research behind that claim isn’t really persuasive:

I’ve argued that the well-known study with a clever name (“The Pen is Mightier than the Keyboard“) is based on a bizarre assumption: “students cannot learn how to do new things.” (If they can’t, why do schools exist?)

I’ve also argued that that the recent study about neural differences between the two note-taking strategies doesn’t allow us to draw strong conclusions, for two reasons:

First: we can’t use it to say that handwriting helps students remember more than keyboarding because the researchers didn’t measure how much students remembered. (No, honestly.)

Second: the students who typed did so in a really unnatural way — one-finger hunt-n-peck. Comparing a normal thing (handwriting) to an abnormal thing (hunt-n-peck) doesn’t allow for strong claims.

So, I’ve been fighting this fight for years.

Both of these research approaches described above overlook the most straightforward research strategy of all: let’s measure who learns more in real classrooms — handwriters or keyboarders!!

A group of researchers recently asked this sensible question, and did a meta-analysis of the studies they found.

The results:

Students who use laptops write more words;

Students who take handwritten notes score higher on tests and exams.

So: there you have it. Handwritten notes REALLY DO result in more learning than laptop notes. I REALLY HAVE BEEN WRONG all this time.

Case closed.

One More Thing…

Like the TV detective Columbo, however, I have just a few more questions I want to explore.

First: I think the case-closing meta-analysis shows persuasively that handwritten notes as students currently take them are better than laptop notes as students currently take them.

But it doesn’t answer this vital question: can students learn to take notes better?

After all, we focus SO MUCH of our energy on teaching better; perhaps students could also do good things better.

If the answer to that vital question is “no” — students CAN’T take better notes — then obviously they should stick with handwriting. This meta-analysis shows that that’s currently the better strategy.

But if the answer is “yes” — students CAN take better notes than they currently do — then that’s really important news, and we should focus on it.

I myself suspect the answer to that question is “yes.” Here’s why:

The 2014 study — “The Pen is Mightier than the Keyboard” — argues that students benefit from taking notes when they do two things:

First: when they write more words. In their research, students who wrote more words remembered more information later on.

Second: when they reword what the teacher said. Students who copied the teacher’s words more-or-less verbatim remembered LESS than those who put the teacher’s ideas into their own words.

This second finding, by the way, makes lots of sense. Rewording must result from thinking; unsurprisingly, students who think more remember more.

1 + 1 > 1

Let’s assume for a moment that these research findings are true; students benefit from writing more words, and they benefit from rethinking and rewording as they write.

At this point, it simply makes sense to suspect that students who do BOTH will remember even more than students who do only one or the other.

In other words:

“Writing more words” + “rewording as I write”

will be better than

only “writing more words” or

only “rewording as I write.”

Yes, this is a hypothesis — but it’s a plausible one, no?

Alas, in the current reality, students do one or the other.

Handwriters can’t write more words — it’s physically impossible — but they do lots of rewording. (They have to; because they can’t write as fast as the teacher speaks, they have to reword the concepts to write them down.)

Keyborders write more words that handwriters (because typing is faster than handwriting). But they don’t have to reword — because they can write as fast as the teacher says important things.

But — wait just a minute!

Keyboarders DON’T reword…but they could learn to do so.

If keyboarders write more words (which they’re already doing) and put the teacher’s idea into their own words (which they’re not currently doing), then they would get BOTH BENEFITS.

That is: if we teach keyboarders to reword, they will probably get both benefits…and ultimately learn more.

In brief: it seems likely to me that laptop notes — if correctly taken — will result in more learning than handwritten notes. If that hypothesis (untested, but plausible) is true, then we should teach students how to take laptop notes well.

I should say: we have specific reason to suspect that students can learn to use both strategies (more words + rewording) at the same time: because students can learn new things! In fact: schools exist to help them do so.

Contrary to my blog post’s title, students really can improve if we help them do so.

Optimism and Realism

I hear you asking: “Okay, what’s your actual suggestion? Get specific.” That’s a fair question.

I – optimistically – think schools should teach two skills:

First: keyboarding. If students can touch type, they’ll be able to type MANY more words than untrained keyboarders, or handwriters.

Remember, the recent meta-analysis shows that students who keyboard – even if they aren’t touch typists – write more words than hand-writers. Imagine the improvement if they don’t have to hunt-n-peck to find the letter “j,” or the “;”.

Second: explicitly teach students the skill of rewording as they type. This skill – like all new and counter-intuitive skills – will require lots of explanation and lots of practice. Our students won’t change their behavior based on one lesson or one night’s homework.

However, if we teach the skill, and let them practice over a year (or multiple years) students will gradually develop this cognitive habit.

The result of these two steps: students will touch-type LOTS more words, and they will reword their notes as they go. Because they get BOTH benefits, they will learn more than the students who do only one or the other.

Now, I can hear this realistic rejoinder: “Oh come on: we simply don’t have time to add anything to the curriculum. You want us to teach two more things? Not gonna happen.”

I have two responses:

First: “developing these two skills will probably help students learn other curricular topics better. Extra effort up front will probably speed up learning (in some cases/ disciplines/grades) later on.”

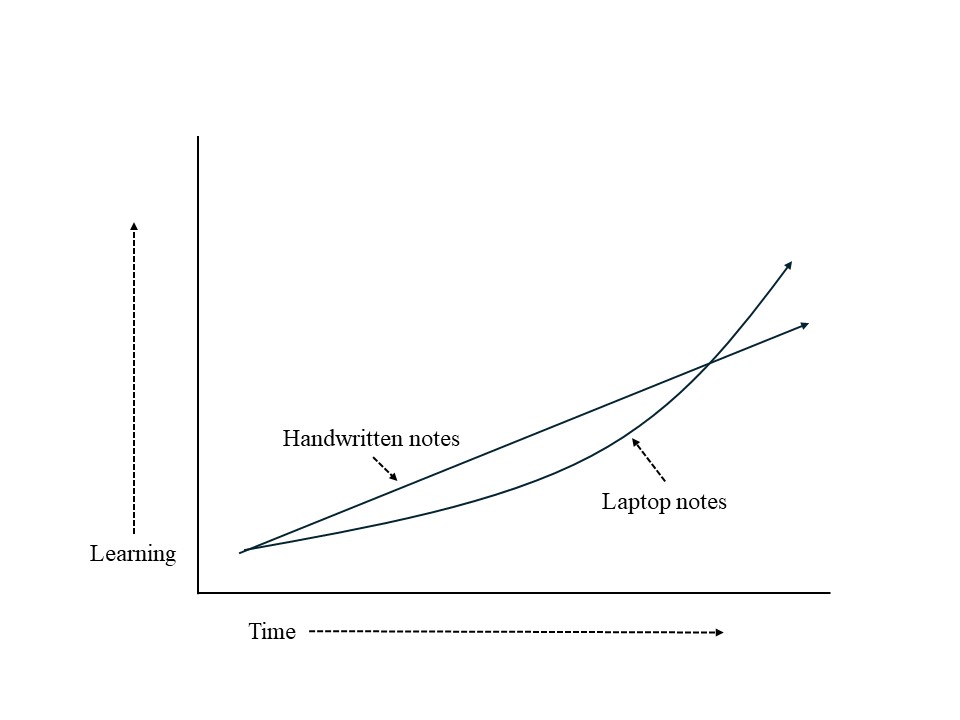

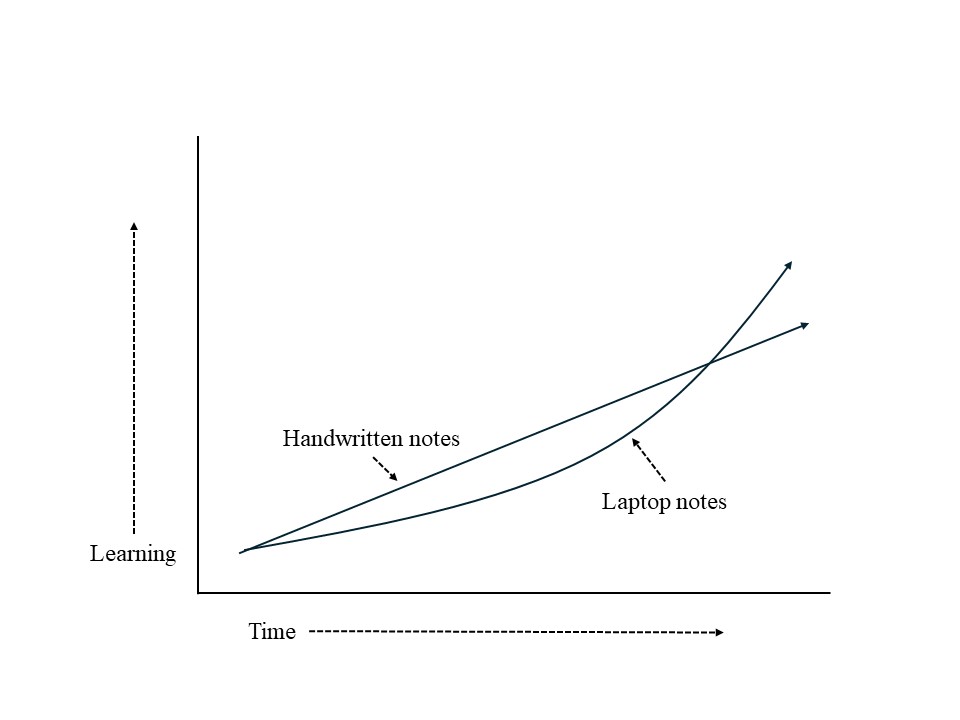

If my untested hypothesis is correct, the progress of learning will look something like this:

In brief:

The title of this blog post is incorrect. Students CAN learn how to do new things – like take better notes by keyboarding well. We might choose not to teach them how to do so, but we should be honest with ourselves that the limitation is in our curriculum, not in our students’ abilities.

Mueller, P. A., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2014). The pen is mightier than the keyboard: Advantages of longhand over laptop note taking. Psychological science, 25(6), 1159-1168.

Van der Weel, F. R., & Van der Meer, A. L. (2024). Handwriting but not typewriting leads to widespread brain connectivity: a high-density EEG study with implications for the classroom. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1219945.

Flanigan, A. E., Wheeler, J., Colliot, T., Lu, J., & Kiewra, K. A. (2024). Typed Versus Handwritten Lecture Notes and College Student Achievement: A Meta-Analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 36(3), 78.