A few years ago, I visited an English Department meeting at a well-known high school. The topic under discussion: a recently published “English Department Guide to Annotation.”

After the meeting, one of the authors asked me what I thought of the guide and the research behind it.

I asked: “Well, what IS the research behind it?”

The teacher answered: “Oh, ALL the research says this.”

Although this answer (“ALL the research shows…”) is quite common, it always makes me nervous.

In the first place, it sounds like a dodge, doesn’t it? It’s the sort of answer I might give if I didn’t actually know much about the research.

In the second place: it’s never true. Because teaching and psychology and research are all so complicated, researchers NEVER get the precisely same answer when they study interesting, complex, and important questions about teaching.

Even retrieval practice — one of the most research-supported teaching strategies we have! — doesn’t have unanimous support in the research literature.

So: what does research say about annotating texts? I recently stumbled across a study that explores this question…

A Promising Start

A recently published study looks quite specifically at the benefits of teaching annotation. In this study, 125 8th grade students in a social studies class learned a specific method for annotation; another 125 served as the control group.

The students who learned this new method got LOTS of practice: at least 100 minutes over 6 weeks. The study used a “business as usual” control group, which means that the teachers just taught as they usually do for the students who didn’t learn about annotation.

The result: impressive!

In brief, the students who annotated thought the method was relatively easy to use. And, they scored higher on a reading-comprehension test.

If you speak stats, you’ll be impressed to see that the Cohen’s d was 0.46: an attention-getting number for a 6-week intervention.

So far, this study gives us reason to focus on teaching annotation.

Subsequent Concerns

And yet, I do have concerns: some specific to this study, and some more generally about applying research to classrooms.

SPECIFIC concern:

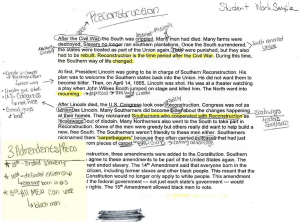

As you can see in the image above, the annotating method includes highlighting. Alas, researchers have looked at highlighting specifically, and found it to be largely unhelpful.

For instance, when John Dunlosky et al. evaluated the efficacy of various study strategies, they didn’t find much to recommend highlighting:

On the basis of the available evidence, we rate highlighting and underlining as having low utility. In most situations that have been examined and with most participants, highlighting does little to boost performance.

It may help when students have the knowledge needed to highlight more effectively, or when texts are difficult, but it may actually hurt performance on higher level tasks that require inference making. (Emphasis added.)

If this annotating method includes a widely-discredited strategy, I worry about the research behind it.

GENERAL concerns

As I’ve written before, I want to offer “research based teaching advice” only if LOTS of research supports the advice. You know your school, curriculum, and students better than I do — so I need SUBSTANTIAL reason to say “do this, not that.”

Alas, we have precious little research into the question of annotation.

I’ve used my go-to resources (scite.ai, connectedpapers.com, elicit.org), and found almost no research pointing one way or the other. (The study described above does mention other experiments … but as far as I can discover none of them focuses precisely on annotation.)

So, yes: we have ONE study saying that this annotation method helped 8th graders learn more in a social studies class. But I don’t think we should be very sure of that narrow finding…much less confident about extrapolating.

That is: do these results tell us anything about annotating in a high-school English class? I don’t think so.

Niche-y, But Important

A final concern merits a brief discussion here.

As noted above, the study uses a “business as usual” control group. That is: some students got A SHINY NEW THING (for 100 minutes!). And some students got … nothing special.

As you can imagine, we might easily conclude that the SHINY NOVELTY — not the annotation specifics — helped the students.

The study would have been more persuasive if the control group had learned a different reading comprehension strategy instead of annotation. In this case, we would have more confidence about the benefits (or lack of benefits) of annotation.

Generally speaking: when a study compares Something to Something Else, not Something to Nothing, it gives us greater reason to rely on its findings.

In Brief

When our students read, we want them to think about the text they’re reading.

We want them to …

… learn the ideas in the text,

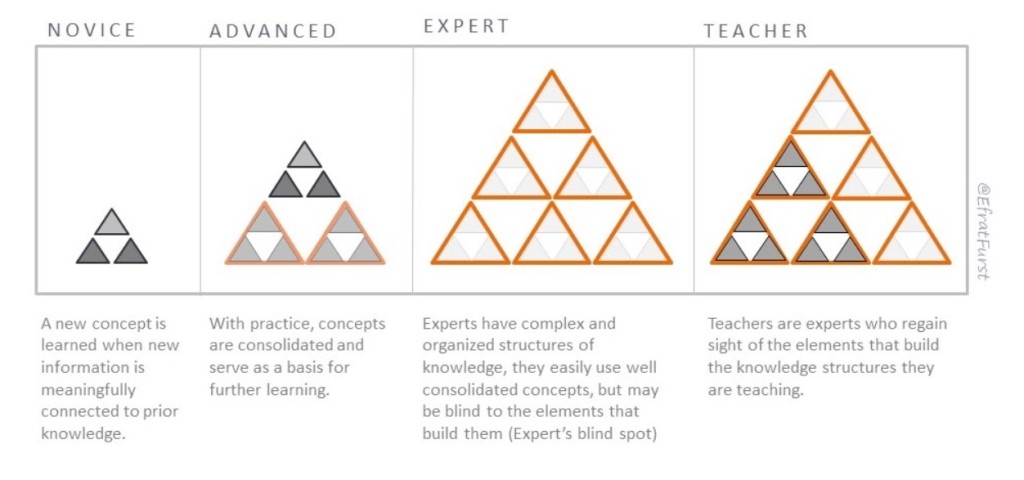

… associate it with their prior knowledege,

… update their schema on the topic,

… consider weaknesses, questions, and omissions,

and so forth.

Is annotating the best way to ensure they do so? I’m not yet persuaded.

If you know of good research on the topic, I hope you’ll let me know!

Lloyd, Z. T., Kim, D., Cox, J. T., Doepker, G. M., & Downey, S. E. (2022). Using the annotating strategy to improve students’ academic achievement in social studies. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 15(2), 218-231.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public interest, 14(1), 4-58.