With the school year starting in just a couple of weeks, Learn Like a Pro: Science-Based Tools to Become Better at Anything by Barbara Oakley and Olav Schewe is an excellent resource to help students start the school year with strong study habits. Using a fun, accessible tone and helpful graphics this book instructs readers about how to manage procrastination, exert self-discipline, stay motivated, study actively, think deeply, memorize new content, take better notes, read more efficiently, and ace the next test. Oakley is a professor of engineering at Oakland University and known for her widely popular massive open online course. Schewe is the founder and CEO of an EdTech start up, Educas.

With the school year starting in just a couple of weeks, Learn Like a Pro: Science-Based Tools to Become Better at Anything by Barbara Oakley and Olav Schewe is an excellent resource to help students start the school year with strong study habits. Using a fun, accessible tone and helpful graphics this book instructs readers about how to manage procrastination, exert self-discipline, stay motivated, study actively, think deeply, memorize new content, take better notes, read more efficiently, and ace the next test. Oakley is a professor of engineering at Oakland University and known for her widely popular massive open online course. Schewe is the founder and CEO of an EdTech start up, Educas.

Part of effective learning and studying involves developing persistence and motivation to stick with one’s studies. One tool Oakley and Schewe recommend to beat procrastination is the Pomodoro technique, which involves remove all distractions, setting a timer for 25 minutes during which one works intently on a single task, then rewarding oneself with a 5 minute relaxing break (i.e., not a break that involves one’s smart phone). Meditation, yoga, and taking time to relax can also help build attention and focus. Removing temptations can make it easier to stick with a goal. Setting specific, measurable, ambitious, realistic, and time limited short- and long-term goals can help increase motivation. Working with others (e.g., in a study group) and finding value in one’s work can also increase motivation. Metacognitive awareness about one’s progress are also helpful. Finally, a healthy lifestyle, which involves physical exercise, high quality and sufficient sleep, and a balanced diet, is key for effective learning.

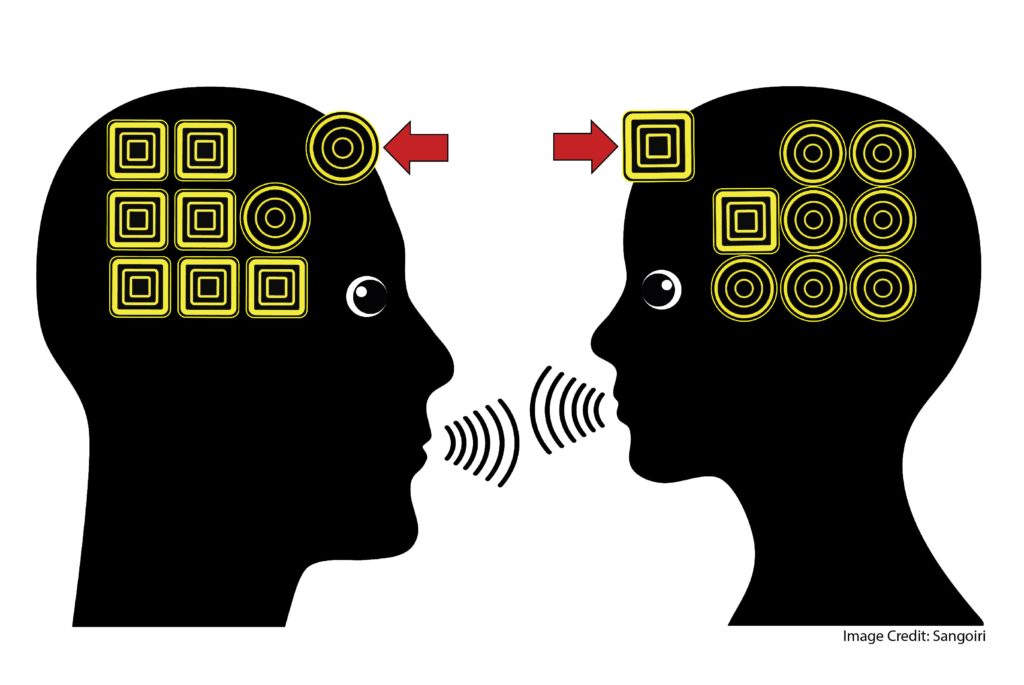

Oakley and Schewe review good study habits. Active studying (e.g., by using flashcards, explaining concepts and their relations to one another, and brainstorming possible test questions) rather than passive studying (e.g., re-reading notes) is likely to yield results. Studying in frequent, small chunks and reviewing, previewing, and mixing content during those chunks of study time is helpful. Sometimes studying involves memorizing ideas so that a student has mental power available to solve advanced problems with simpler ideas already clearly in mind. Using acronyms, metaphors and other memory tricks can help make ideas stick. Working through practice problems is a great way to check for understanding while studying.

Being a good test taker involves some different skills than being a good student or studier. Oakley and Schewe suggest reading through test instructions and questions carefully, checking the time while taking the test, starting the test by previewing the hardest questions so one can passively think about them while answering other questions, and reviewing answers at the end.

Oakley and Schewe conclude the book with a checklist of ways to become an effective learner. To learn more about these and other helpful study suggestions you may be interested in Learn Like a Pro, as well as other works by Oakley, including Learning How to Learn.

Oakley, B. & Schewe, O. (2021). Learn Like a Pro: Science-based Tools to Become Better at Anything. St. Martin’s Publishing Group.