We know that working memory overload brings learning to a halt. For that reason, teachers do almost everything we can to teach students within their working memory limits.

We might ask ourselves pointed questions to anticipate WM overload before it happens: e.g., “does my lesson plan include too many instructions?”

An equally vital task: we want to recognize WM overload while it happens. If I can see that my lesson plan has exceeded WM max, then I can make helpful changes on the fly. In today’s blog post, I’ve got two quick ways to do just that.

The Big Tell

Picture this scene. My English class begins with a scripted definition:

“Everyone, please write down the definition of the word gerund. The definition has three parts:

A gerund started life as a verb, is now being used as a noun, and ends in -ing.”

Immediately Rory’s hand goes up: “I’m so sorry Mr. Watson, I spaced out for a moment. Can you please repeat that?”

I do.

Charlotte waves at me: “Wait, started life as a verb, or a noun?”

Me: “Started life as a verb, is now being used as a noun.”

Caleb jumps in: “What are the exceptions to the ‘-ing’ part?”

No exceptions. Not a single one.

Helen has something to say: “I’m still confused. It’s a verb that ends in -ing? Don’t all verbs end in -ing?”

By this time, I should be getting the working-memory message. In essence, these students are all asking the same question: “I didn’t understand what you just said. Could you repeat it?”

Here’s my observation: when my students ask me the same question several times in a row, I have almost certainly overloaded their working memory. Now that I recognize WM overload while it’s happening, I can make a mid-course correction.

The Big Tell, Take II

Let’s replay that scene, but this time take note of my own thoughts and feelings as I go.

When I first present my definition, I’m feeling confident. This simple definition–it has only three parts!–captures the gerund’s key elements in a lively way. This section of class is off to an excellent start.

When Rory asks me to repeat the definition, I’m surprised…but not surprised. High school sophomores aren’t famous for their attention span, especially during a grammar class. In any case, repeating the definition will probably help others in the class.

Charlotte’s question knocks me off my stride. I just answered her question. In fact, I answered it twice in a row. What’s going on here?

Exceptions, Caleb? Who said anything about exceptions? If there were exceptions, I would have made that point in the definition. By now I’m straight-up frustrated. I offered such a simple definition, and class has already devolved into a muddle.

By the time Helen opines that “all verbs end in -ing,” I can’t remember: why did I go into teaching?

Notice the working memory dynamics in this short exchange.

- First: I designed this section of the lesson plan badly and created cognitive overload.

- Second: my students reacted–reasonably enough–by trying to fix my mistake. They knew that they needed to understand this definition, and so they kept asking questions to clarify the concept.

- Third: their repeated questions vexed me. Although those questions were a predictable response to working memory overload, I got frustrated with them for peppering me with foolishness.

In other words: my own emotional response is a second clue that working memory overload is happening right in front of me, right now. If I miss the first tell–their repeated questions–I might register the second tell–my own growing irritation. Whichever clue I spot, I can use that feedback to guide a mid-lesson course correction.

Problem Recognized; Problem Solved

Once I learn to recognize these two signs–students’ repeated questions, my own growing frustration–I can switch to solution mode.

In this case, I should (at a minimum) write the definition on the board. (Why didn’t I think to do that in the first place?) If my students can read the definition, they don’t have to hold all the words while they’re writing each one down.

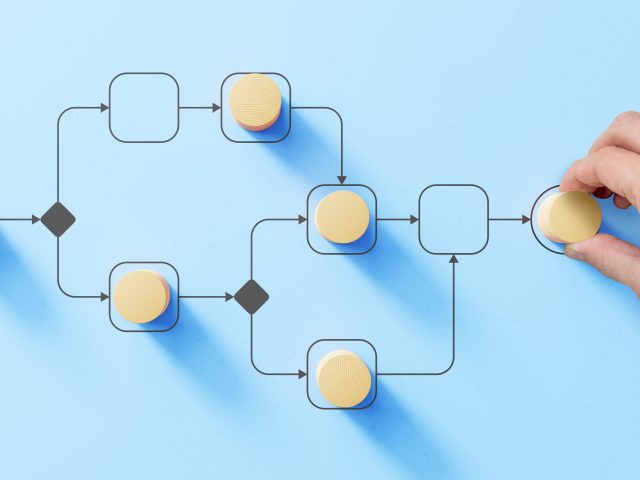

Even better—as Adam Boxer has explained in his excellent book—I might reverse my order of operations. In this lesson plan, I started with an abstract definition, and then planned to give concrete examples. Result: I overloaded working memory with abstract concepts even before I got to the specifics.

As Boxer explains, I should instead start with the specific examples and then graduate to the abstract definition. This direction of travel reduces WM load.

Of course, other teaching missteps require alternative solutions. For instance, I might rely on dual coding to redistribute WM load.

Whatever the solution, my ability to spot a working memory problem in the moment means I’m likelier to solve that problem…and my students will learn more.