Obviously, we want our students to learn science. But: what if they struggle to learn the science by reading?

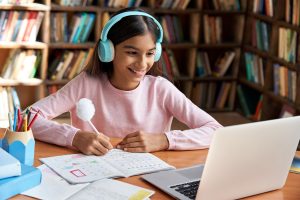

One solution: we could use VIDEOS to teach science. Videos can transform the written words into an audio track. Voila — no reading required!

A recent study explores this very question. To paraphrase its conclusion: “YUP — students learn more from science videos, so we can/should use them in science classes.”

While the study itself strikes me as well done in a number of ways, I want to push back against this conclusion. Ultimately, this disagreement might reveal the tension between a researcher’s perspective and a teacher’s perspective.

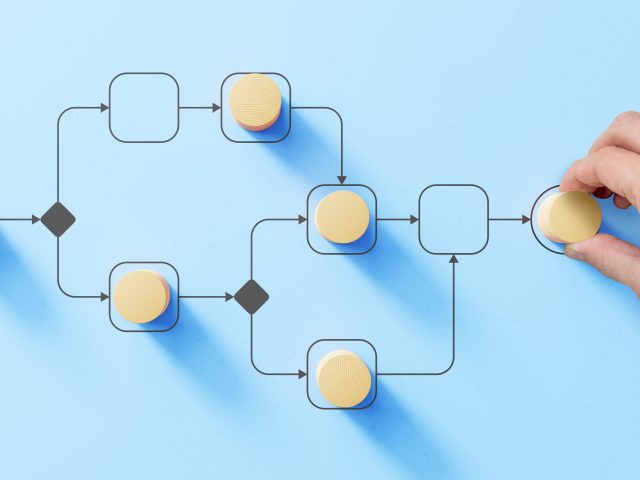

The outline for this post:

- I’ll start by summarizing the study, and noting its strengths

- I’ll then try to explain why I’m not persuaded that this study should make science teachers favor videos — even for weaker-than-average readers.

All The Right Steps

Doing education research well requires enormous care, because it can go wrong in so many different ways. Consider all the expectations that we have — and should have! — for research.

- We want to have enough participants in the study for the results to be meaningful.

- We want researchers to compare plausible alternatives — not just show that “doing something” is better than “doing nothing.”

- We’d like reports on meaningful results — not just “did the students have fun” or something like that.

- We’d be REALLY happy if the research took place in typical school conditions — not in some hermetically sealed zone that bears little resemblance to actual classrooms.

- We expect lots of statsy/mathy results (even if we don’t promise to read them carefully).

And so on. If researchers skip any of these steps, we can complain from the sidelines: “this study doesn’t include an ‘active control group,’ so we shouldn’t rely on its results.” (Honestly, I’m one of the people who object to studies without active control groups.)

Because I’m so aware of these expectations — and lots more — I felt more and more impressed as I made my way through this study. This team has clearly thought through many of the possible objections and found ways to anticipate and mollify them.

- Enough participants? More than 100.

- Active controls? Students learned by watching videos, or by reading an illustrated text (with identical words!). In my view, that’s an entirely plausible comparison.

- Meaningful results? Researchers measured how well the students remembered and transfered their learning…up to a week later!

- Within a school? Yup. In fact, students had RECESS in the middle of the study, because that’s how they roll in Finland.

- All the stats? Yes. (More on this point in a minute.)

Thus, I was inclined to be persuaded that, as the abstract says:

The results indicate that videos are beneficial to most children across reading skill levels, especially those with weaker reading skills. This suggests that incorporating videos into primary school science intruction supports diverse learning needs associated with weaker reading skills.

By the way, in this case, “primary school” includes 5th and 6th grade.

A Teacher Has Doubts

Despite this study’s strengths — and I’m being quite serious when I compliment them — I was struck by the actual statistical findings.

The research team focused on three results:

- how much cognitive load did the students experience while watching videos or reading illustrated texts?

- how much difference did video vs. illustrated text make for remembering the information?

- how much difference it make for using information in another context — that is, for transfer?

To answer these questions, they focused on a statistical measure called “R²ₘₐᵣ”. As is always true with stats, it’s tricky to explain what they mean. But here’s a rough-n-ready explanation.

Let’s say that when I study for a quiz using Method A I score 0 points, and when I study using Method B I get 100 points. The R²ₘₐᵣ tells me how much of that difference comes from the two different methods.

So, if R²ₘₐᵣ = .25, that means 25% of the difference between the two scores came from the difference in the two study methods. The other 75 points came from other stuff.

Typically, according to this measure:

- any R²ₘₐᵣ bigger than 0.25 is “large,”

- a value between .09 and .25 is “medium,” and

- a value between .01 and .09 is “small.”

Now that we have a very introductory understanding to this measurement, how meaningful were the results in this study?

- The “cognitive load” R²ₘₐᵣ was .046: right in the middle of “small.”

- The R²ₘₐᵣ for remembering information was .016: barely above the bottom of the scale. And

- R²ₘₐᵣ for transferring information was .003. That’s too small even to register as small.

In brief: did the researchers find STATISTICALLY significant results? It seems they did. Did they find MEANINGFUL differences between videos and illutrated texts? I’m not so sure.

Opportunity Costs

My objection at this point might reflect this difference between a researcher’s perspective and a teacher’s perspective.

The researchers can — entirely reasonably — say: “we ran a scrupulous experiment, and came up with statistically significant results. The data show that videos helped students learn science content better than illustrated texts. Teachers should at least think about using videos to teach science — especially for weak readers.”

As a teacher, my perspective has this additional variable: one of school’s core functions is to teach students to read. And: they get better at reading by — among other strategies — practicing reading.

In other words: according to this study, the benefits of video are so small as to be statistically almost invisible. The benefits of reading practice are — over time — likely to be quite important. I hesitate to give up on one of school’s essential functions (reading) to get such a small benefit (marginal increase in science knowledge) in return.

TL;DR

Someone might say to you — as a friend said to me — “this study shows that we should use videos to teach science content.”

If you hear that claim, be aware that this well executed study found only minute differences between videos and illustrated texts. We should consider this finding alongside a clear understanding of our broader educational mission: teach ALL students to read.

Haavisto, M., Lepola, J., & Jaakkola, T. (2025). The “simple” view of learning from illustrated texts and videos. Learning and Instruction, 100, 102200.