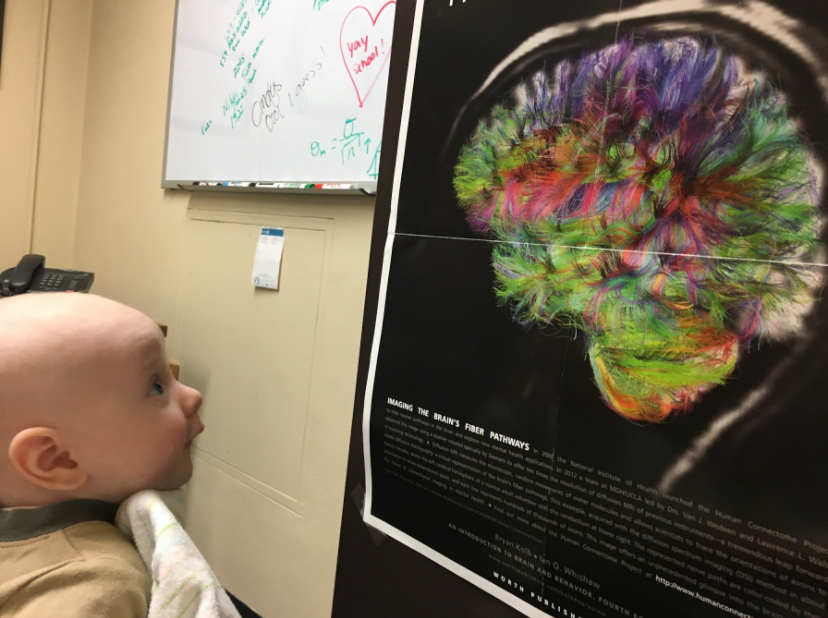

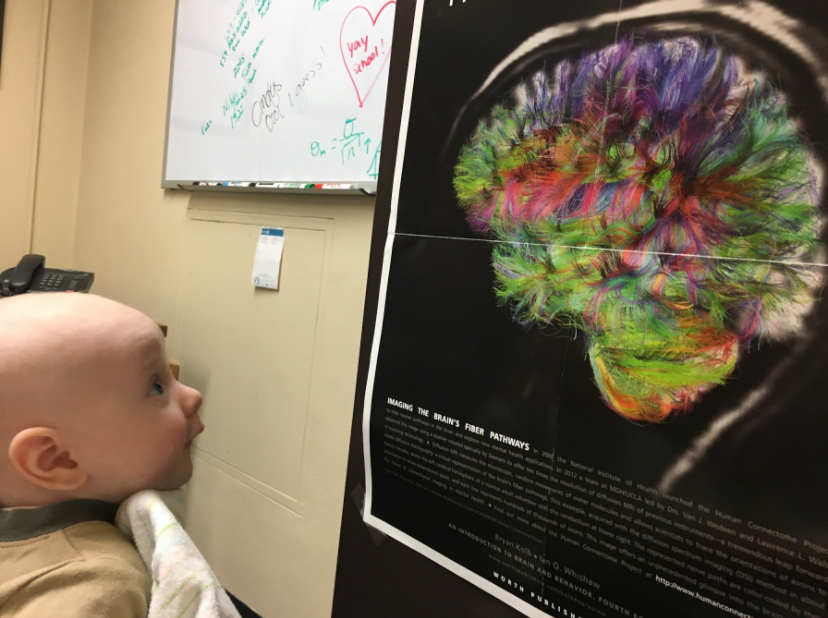

When our students learn — or pay attention, or feel motivated — all sorts of amazing things happen in their brains. Neurons connect and neurotransmitters zip. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) coordinates executive functions; the default mode network (DMN) helps consolidate prior learning. It’s all so cool!

A recent study invites us to reconsider: how do we know about all that brain activity in all those brain regions?

One way to study brain activity goes by the cumbersome name “functional magnetic resonance imaging,” aka fMRI. In theory, fMRI tells us what parts of the brain are working and when. So:

- If students are effectively task switching — that is, enacting executive functions — their PFC “lights up.”

- If students are letting their thoughts wander freely as they consolidate their learning, the DMN “lights up.”

When you see those colorful brain images, the highlighted areas show what regions have been activated during specific mental processes.

Most fMRI studies reach these conclusions by relying on a clever proxy. Here’s the logical chain:

- When neurons activate, they use up oxygen.

- The brain resupplies that oxygen – in fact, oversupplies that oxygen – by increasing blood flow to the region.

- By tracking changes in blood oxygenation, therefore, we can draw reasonable conclusions about neural activity.

In brief: changes in blood oxygenation reveal mental work in very specific regions of the brain.

That’s what most fMRI does. If blood oxygenation CHANGES in the PFC after students effectively task switch, we conclude that executive functions “happen” in the PFC. If blood oxygenation changes in the DMN when students let thoughts wander freely, we conclude that mind wandering “happens” in the DMN.

Such conclusions just make sense.

Rethinking Core Assumptions

But wait just one minute: what if that proxy is wrong? What if the foundational assumption of fMRI analysis just ain’t so?

Last month, a research team published a simply astonishing study challenging the standard interpretation of most fMRI analysis. Instead of measuring neural activity by the blood-oxygenation proxy, they measured it more directly. (To be precise, they used a much better proxy: oxygen metabolism.)

They found that:

- In some cases, blood oxygenation changes do correlate with the more precisely measured metabolic activity. So: yes, sometimes the standard fMRI interpretation path is true.

- But in other cases, blood oxygenation changes in the opposite direction of the more precisely measured metabolic activity. In these cases, the standard interpretation is BACKWARDS.

We should pause to let that finding sink in. If these scholars are correct, then the logic governing fMRI interpretation for DECADES has been — at least at times — pointing us in the wrong direction.

Frying Pan, Fire

In my quick summary above, I wrote that “in some cases” the interpretation is backwards. We should ask: how many cases? If this backwards response happens 1% of the time, that’s an interesting quirk, but perhaps not terribly important.

Well, brace yourself.

- Across the cortex, this study finds a backwards response roughly 40% of the time.

- The backwards response is especially common — more than 60% of the time — when brain regions appear to “deactivate.” (This finding matters so much to education research because — according to the traditional interpretation — the DMN “deactivates” during focused mental tasks.)

- Even when cortical brain regions appear to “activate,” the backwards response still occurs about 30% of the time.

Even worse:

- In most cases, the backwards response isn’t a stable feature. SOMETIMES a specific brain region shows this backwards response, and sometimes it doesn’t.

To put the matter starkly: in brain regions highly relevant to education (e.g., the DMN), we simply do not know if most of the fMRI studies we’ve been relying on accurately describe which regions are more or less active. If the signal we use to infer brain activity often points in the wrong direction, then we can’t be confident that many published interpretations are correct. They could be 60% wrong … and that’s A LOT of wrong.

Let me summarize this grim news in one sentence:

Because blood-oxygenation doesn’t reliably correlate with neural activity, our default way of interpreting standard fMRI doesn’t reliably hold.

Not So Fast

Before I throw out decades of educational neuroscience, I should acknowledge several important caveats:

First: I am not a neuroscientist. I know more about fMRI than most people, but this study happens at a level of technical analysis WAY outside of my own direct knowledge. I’ve done my best to understand its claims, but I could have misunderstood.

Second: because fMRI is so technical, I’ve had to simplify the argument here substantially. I’ve tried to simplify without oversimplifying. But to keep this post readable, I’ve had to err on the side of brevity and clarity.

For instance, throughout this post, I’ve used the phrase “most fMRI” for a reason. This problem applies to the most common kind of fMRI: “blood oxygen level dependent,” aka BOLD. There are other kinds of fMRI – more complex and expensive — and the fears outlined above don’t apply to them (as far as I know).

This point matters a lot. If those other kinds of fMRI support the conclusions that BOLD fMRI has reached, then we might heave a sigh of relief and go on about our business. Of course, other kinds of brain scans — EEG, FNIRS, PET — might also confirm the now-wobbly BOLD fMRI conclusions.

Third: one study is just one study. Until this study has been replicated, we should remain open to the possibility that this research team just got it all wrong. (BTW: they ran their own mini-replication, and came up with similar results.)

Hope?

Neuroscience is a kind of biology. It can tell us what IS happening in the brain, but not what teachers OUGHT to do about that neural activity. (If you teach philosophy, you will recognize David Hume’s “is/ought gap” here.)

For instance, neuroscience tells us what IS happening when new long-term memories form: neurons join together into new neural networks.

But that neuro-biological IS doesn’t give teachers an OUGHT; we don’t know what to DO to cause learning to happen.

Instead, psychology gives us that OUGHT. When teachers learn about mental functions – memory, attention, motivation – that knowledge helps us teach better. We ought to promote desirable difficulties; we ought to focus students’ attention; we ought to manage the working-memory demands of the classroom.

The potential revolution in interpreting BOLD fMRI results might change our understanding of what IS happening in the brain. But it doesn’t change our OUGHT. No matter what neurons are doing within the skull, teachers should still promote desirable difficulties and focus attention and manage WM load.

That’s the hope: teachers can focus on what psychology tells us about learning, confident that our work doesn’t depend on getting the neuroscience exactly right. That neuroscience underneath is fascinating—but thankfully, we don’t need to wait for it to be settled before we can teach well.

Epp, S. M., Castrillón, G., Yuan, B., Andrews-Hanna, J., Preibisch, C., & Riedl, V. (2025). BOLD signal changes can oppose oxygen metabolism across the human cortex. Nature Neuroscience, 1-12.