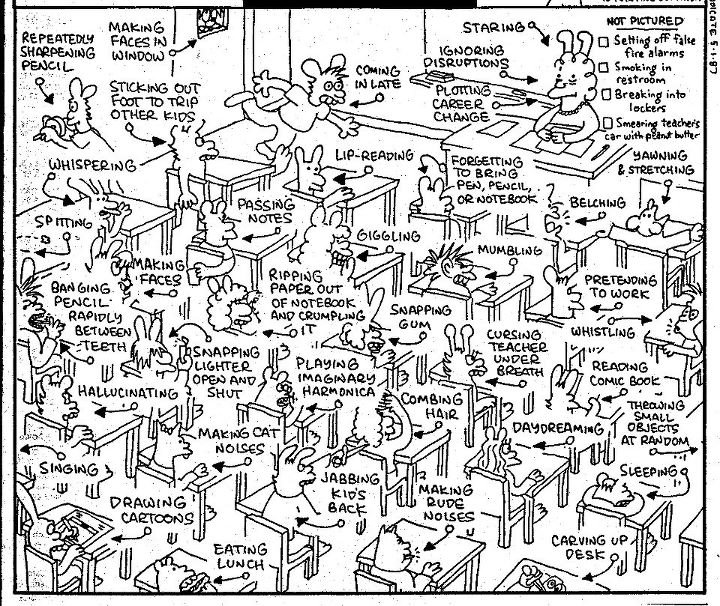

In the spirit of April Fool’s Day, I thought it would be fun to consider several of the false — even foolish — beliefs that people often have about brains. Take a look at the six statements below and judge whether each is true or false – a learning fact or a learning myth. Then, after the brain break in the middle of the article, check out the answers. Enjoy.

- Hemispheric dominance in the brain means some people are dominantly left brained (more analytical), while some are dominantly right brained (more creative)

- Some people are kinesthetic learners, some are auditory learners, and some are visual learners.

- Lecture is an outmoded form of teaching

- Male and female brains are significantly different

- Typing notes in class is just as effective as handwriting them

- Rereading notes is a good way to prepare for a test, so teachers should actively coach this skill

- False: There is no such thing as left/right brain dominance. All thinking tasks involve multiple parts of the brain working together in a coordinated way – some on the left side, some on the right. This coordination is helped by a massive group of fibers called the corpus callosum that links the two sides.

- False: each student has different current strengths and weaknesses, and it is good for students and teachers to be aware of these. But research suggests that labels like “kinesthetic learner” are harmful because they can become self-fulfilling prophecies. In fact, neuroplasticity means that current strengths and weaknesses can change over time with the thoughtful use of strategies. [1]

- False: Core knowledge is a fundamental part of any learning episode. Lecture is one method to use to help build this core knowledge. But to be effective, it should be used strategically, and in conjunction with other methods. In particular, teacher should use strategies that require students to recall knowledge, such as formative assessments, and ones that require students to use the knowledge in a novel context. The goal is to build knowledge that is durable and flexible.

- False: Though there may be subtle differences between male and female brains, the normal and natural range of differences within each gender is far, far greater than the differences between them. There is absolutely no significant evidence to suggest that the genders learn or should be taught differently. This myth might stem from a misinterpretation of books such as The Essential Difference: Men, Women, and the Extreme Male Brain, which focused largely on patients with autism. [2]

- False (for most people): “Because handwriting is slower, we are forced to interpret and paraphrase what a speaker says instead of simply producing a transcript. This act of synthesis leads to better semantic processing, which means that schematic changes to long-term memory are likely to be taking place as notes are taken. Typing, because it demands less of us, results in less change to long-term memory.” [3]

- False: Rereading is not the best method because it can give “the illusion of fluency” – students become familiar with the words and think they “get it” when they might not. Research suggests that active recall methods:

- getting out a piece of paper and writing out everything you know then checking your notes,

- repeatedly working on practice questions, checking your answers, then checking your notes.

How did you do? Anyone get 6 out of 6? I know, it was a bit cheeky to give you six false ones. Whilst this is a bit of fun, these perhaps trivial sounding statements can have profound effects on learning – and all are easy to address.

Numbers 1, 2 and 4 lead to students defining themselves in limiting ways that often become self-fulfilling prophecies. “I can’t do that, because my brain or my learning style is like this.”

All students — from the academic high fliers to those with learning challenges — are good at some cognitive demands and weaker at others. And it is good to know these. But it is important to remember that they are current strengths and weaknesses. Neuroplasticity means that each student’s brain is constantly rewiring – an interplay of genetic coding and the environment it is experiencing. The reflective, iterative use of strategies, played out over time, is a powerful thing. Hard work plus strategic work is a brain changer.

At St. Andrew’s, we often get students arriving from other schools who have suffered for years from being told that they are, say, a visual learner or a left brained person — so much so that they initially shy away from certain tasks believing that failure is certain because they are just not that kind of learner.

But in a community that refuses to believe these neuromyths, that challenges students to work at finding strategies in all areas that work for them, a magic happens. We see students not just taking risks in areas that they had previously shut off, we see them develop a self-awareness that they are that much more whole of a person. And this brings a happiness and confidence that is well earned.

Numbers 3, 5 and 6 are simple traps that we can find ourselves walking into, in part because there is so much brain-rubbish out there. Sometimes the classic methods are still great methods – but it helps to use them with the added wisdom that they are just the right thing at just the right time.

I recently told my students the story of how the profession of teaching’s reluctance to use research evidence to inform practice is a bit like going to your doctor and having them get out a jar of leeches. Aidan immediately said to me, “You know, Dr. Kelleher, leeches are still used in medicine for some things, like cleaning up tissue in certain kinds of surgery.” A great riposte!

But I think it just aids the metaphor. Much of the classic repertoire of teaching is still great, and well supported by research evidence. But we need to know what is and what isn’t. Leeches might still be the best tool available, but we need to know where to use them, are where to employ methods that might result in a better outcome.

Most importantly, though, these six things are simple ways to use research to inform your practice. Beginning your journey as a research informed teacher is actually quite easy – just take these six things on board. Then pass them on, the word needs to be spread. As ever, if the answers are problematic to you, or raise more questions, please get in touch.

[Editor’s note: if you’d like to see my own thoughts on typing vs. handwriting notes, click here. The short version: I think that–if done correctly–laptop notes will be as effective as handwritten notes; and that researchers who claim the contrary are dramatically overinterpreting their data.]- Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles concepts and evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9(3), 105-119. [link]

- For an easy read into this subject: Eliot, L. (2010). Pink brain, blue brain: How small differences grow into troublesome gaps — and what we can do about it. Boston: Mariner Books.

- David Didau, @LearningSpy, Human’s Can’t Mutitask [link]