Here’s an odd brain theory to start off your day:

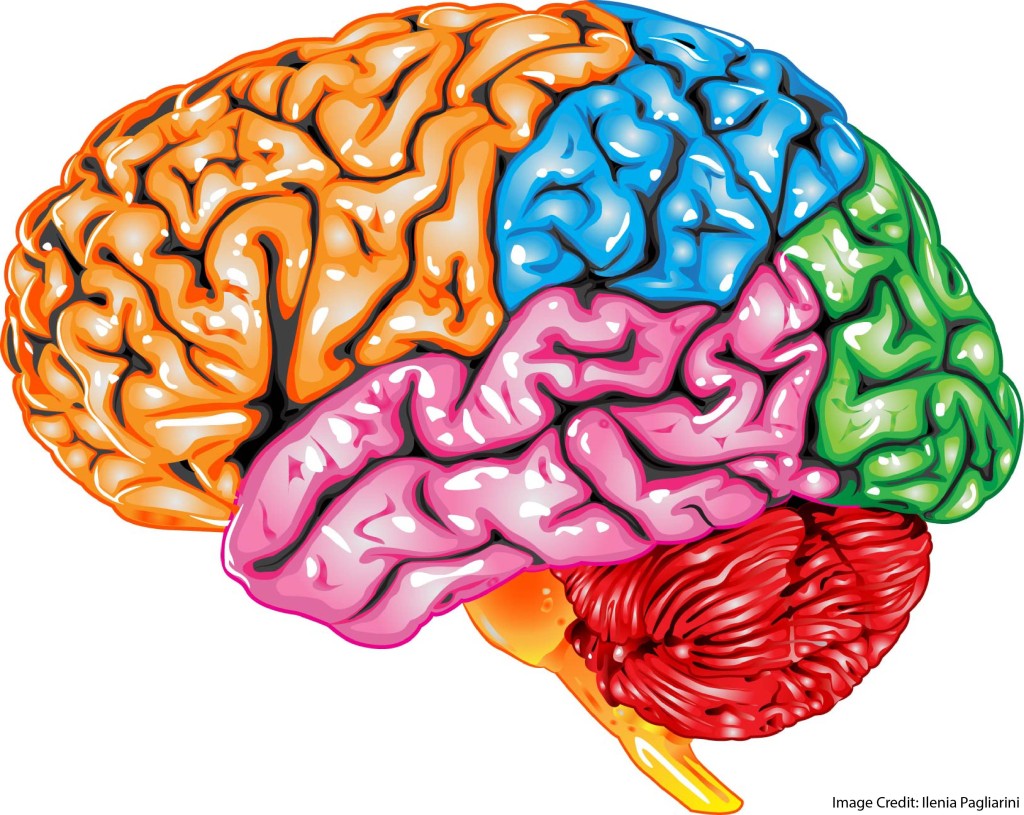

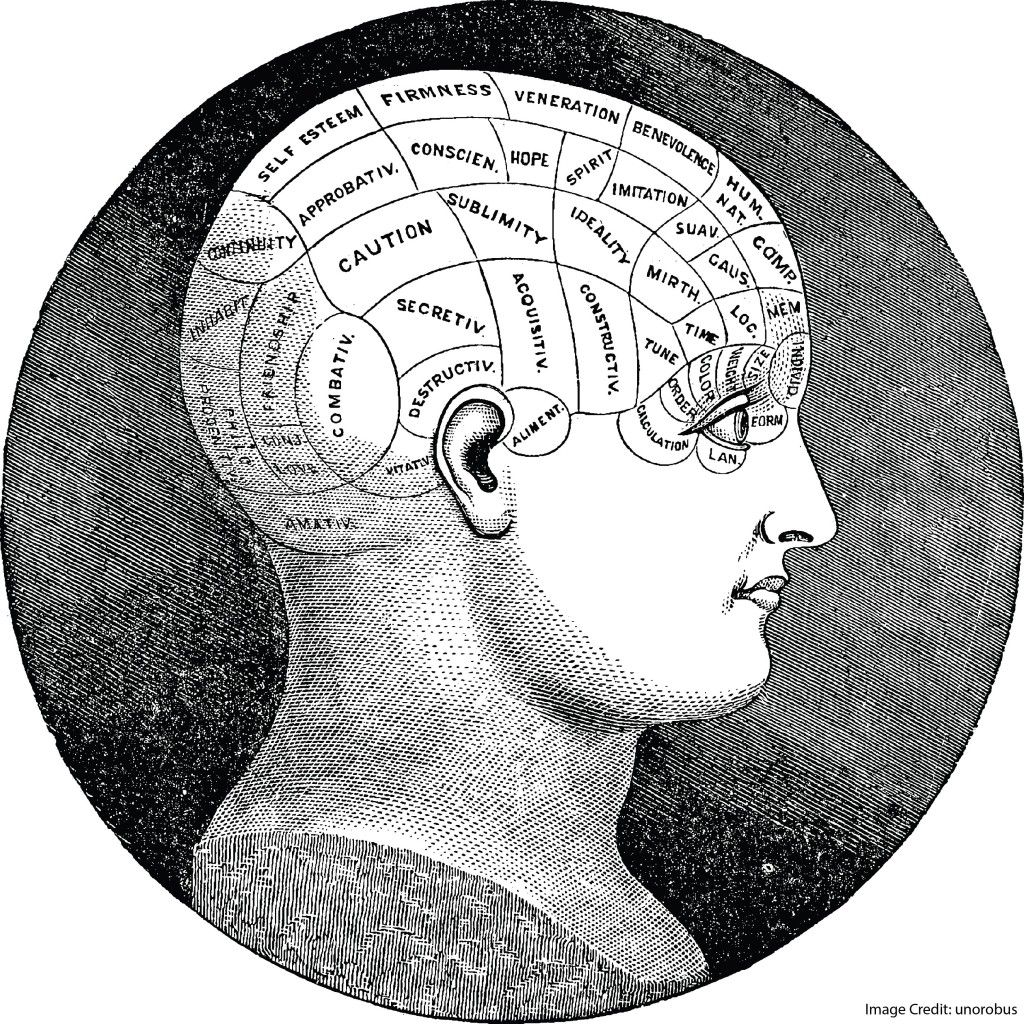

Let’s assume that particular regions of your brain produce particular mental abilities or habits. For instance, let’s say that this part of your brain right here is the generosity center of the brain.

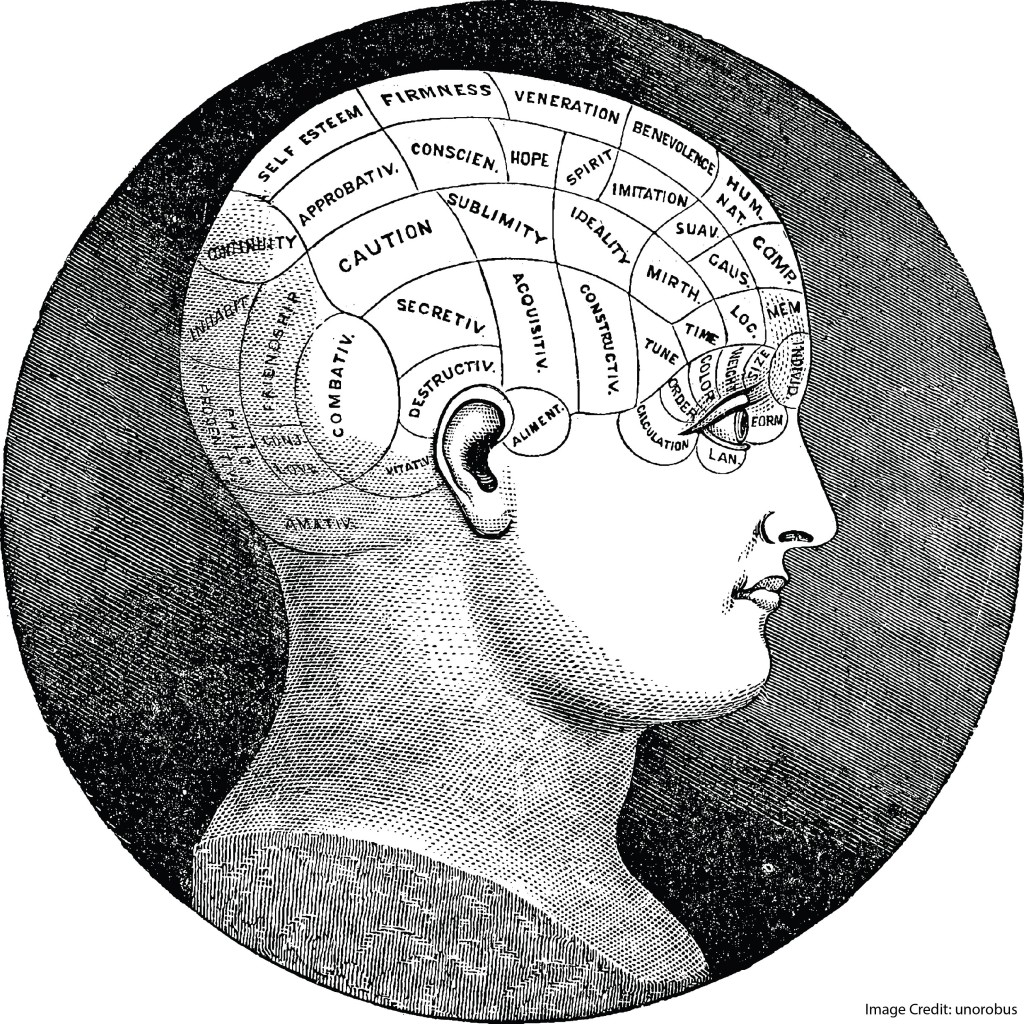

So, if I feel a bump on your head above the “generosity region” of the brain, I can assume that this part of your brain is unusually big, and that you are therefore unusually generous.

However bizarre this theory might sound, phrenology was quite popular in the early 1800s. Most often attributed to Franz Joseph Gall–and, of course, popularized and spread by others–this theory produced a mini-industry of diagnosing people’s characters by feeling the bumps on their heads.

The Larger Question

Phrenology is but the most extreme position in an ongoing debate.

On one side of this debate–the phrenology & co. side–we can think about mental activities taking place in very specific parts of the brain. We can say that the amygdala is the “fear center” of the brain, or that the hippocampus is the “memory center,” or the anterior cingulate cortex the “error-detection center.”

The other side of the debate argues that all brain functions take place in wide networks that spread across many parts of the brain. Memory isn’t just in the hippocampus: it includes the prefrontal cortex, and sensory regions of the neocortex, and the striatum, and the cerebellum…it happen all across the brain.

So, here’s the question: which side of the debate has it right?

A Very Specific Answer

I thought about this debate when I read a recent article about language areas in the brain. Here’s a one-paragraph summary of that article, written by the authors. (Don’t worry too much about the “BA” numbers; focus on the broader argument):

The interest in understanding how language is “localized” in the brain has existed for centuries. Departing from seven meta-analytic studies of functional magnetic resonance imaging activity during the performance of different language activities, it is proposed here that there are two different language networks in the brain: first, a language reception/understanding system, including a “core Wernicke’s area” involved in word recognition (BA21, BA22, BA41, and BA42), and a fringe or peripheral area (“extended Wernicke’s area:” BA20, BA37, BA38, BA39, and BA40) involved in language associations (associating words with other information); second, a language production system (“Broca’s complex:” BA44, BA45, and also BA46, BA47, partially BA6-mainly its mesial supplementary motor area-and extending toward the basal ganglia and the thalamus). This paper additionally proposes that the insula (BA13) plays a certain coordinating role in interconnecting these two brain language systems.

Got that? [I put those words in bold, btw.]

In brief, researchers argue that language requires two sets of neural networks. One network, “Wernicke’s area,” has both a core and a periphery. The other, “Broca’s,” is itself a complex. And, these two networks are coordinated by the insula.

(If you want to reread that paragraph now that you’ve seen the summary, it might make more sense.)

“Both-ily”

As I read that summary, I think the authors are saying that both theories about brain structure are partly true.

Understanding language takes place in Wernicke’s area–which is itself a pair of networks. Producing language takes place in Broca’s area–which is a complex. And those networks and complexes communicate through the insula.

In other words: specific mental functions take place in specific places, but those “places” are best thought of as interconnected networks.

In grad school, a discussion group I was in once debated the theories I outlined above. Our question was: “when we study brains, should we think locally or network-ily?” After an hour of heated discussion, we reached a firm conclusion: we should always think “both-ily.”

One More Famous Example

You probably know the story of Henry Molaisson: a patient whose hippocampi were removed to cure his epilepsy.

The good news: his epilepsy was (largely) cured.

The tragic news: he could no longer form long-term declarative memories.

From H.M.’s example, we learned to think about long-term memory locally: clearly, the hippocampus is essential for creating new long-term declarative memories. After all, if you don’t have one, you can’t learn new things.

(This hypothesis was confirmed with a few other patients since H.M.)

But, from H.M.’s example, we also learned to think about long-term memory in networks. He didn’t learn things when told them, but he could learn new things.

For example: when asked how to get to the kitchen in his new house, he couldn’t answer. He just didn’t “know.” (That is: he didn’t know in a way that would allow him to explain the answer.)

But, when he wanted a cup of tea, he went to the kitchen and made one for himself. Clearly, he did “know.” (That is: he knew in a way that would allow him to get to the kitchen–as long as he didn’t have to explain how he got there.)

When thinking about H.M., should we think “locally” or “network-ily”? I say: think both-ily.

The Bigger Message

When you hear from self-proclaimed brain experts who tells you that “the wrinkle-bop is the juggling center of the brain,” beware.

If those “experts” go on to explain that this sentence is a crude shorthand for “the wrinkle-bop is a very important part of a complex network of areas involved in juggling,” then you’re okay.

But if those “experts” just stop there–in other words, if they really think “locally,” not “both-ily”–then you should be suspicious.

You might conclude that their teaching advice is valid, and decide to give it a try. But, don’t rely on their neuroscience expertise. They are, in effect, just reading the bumps on your skull…