Oliver Caviglioli has written a book about dual coding. (Nope. That’s not it. Let me start again.)

Oliver Caviglioli has created a new genre.

It’s 50% scholarly essay, 40% graphic novel, 5% Ulysses, and 5% its own unique magic.

Let me explain.

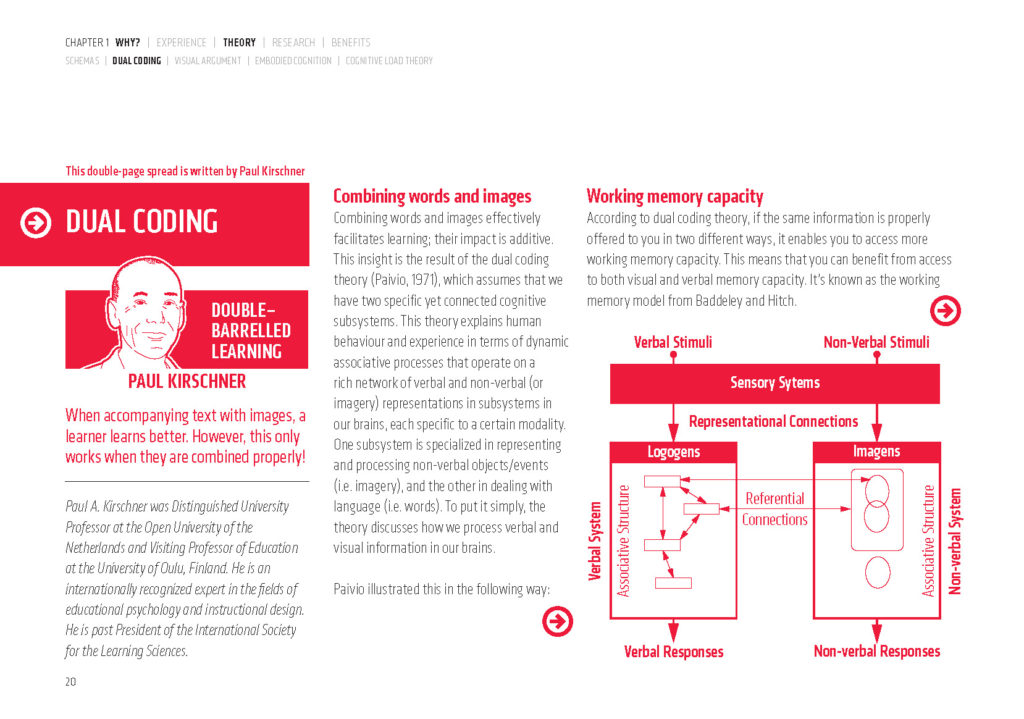

Back in the 1960s, Allan Paivio developed a theory about cognitive processing. The short version is: humans can process information more effectively if we take in some of it through our eyes, and some through our ears.

Because it encourages us to use two different channels for processing, it’s called dual coding.

Writing a book about dual coding, however, invites paradox. Books, especially traditionally scholarly books, rely almost exclusively on words, and have only occasional images.

But such a “traditional scholarly book” would contradict the very theory that Caviglioli wants to explain. So, he had to come up with something new.

Indeed he has: Dual Coding with Teachers is like no book you’ve seen before.

The Parts

Caviglioli divides his “book” into seven “chapters” — although each is more a free-standing entity than the word “chapter” suggests. (For the sake of convenience, I’m just going to call them chapters.)

Chapter 1, called “Why?”, offers a substantial explication of Paivio’s theory. It goes into schema theory, different conceptualizations of working memory, and even embodied cognition. It reviews lots of persuasive evidence for many segments of the theory.

Following chapters take up different topics for using dual coding theory thoughtfully.

Chapter 2 (“What?”) sorts uses of the theory into specific categories: graphic organizers, walkthrus, sketchnotes, and so forth.

Chapter 3 (“How”) explains the process of creating a successful version of each category.

In every case, Caviglioli combines words with icons and images to map out the concepts and their relationships.

That is: he employs dual coding to explain the theory and practice of dual coding.

Said in other words: readers can learn as much about dual coding by studying the design and execution of the book as they can by studying the book’s contents.

The Sum of the Parts

I suspect few people will want to treat Caviglioli’s creation like a typical book. That is: you won’t read it from beginning to end.

Instead, you’ll probably use it more like one of those 800 page manuals that used to come with complex software. You’ll dip in and out; leaf around looking for pointers or for inspiration.

If you’re having trouble deciding which kind of visual to use, have a gander at chapter two.

If you’re dissatisfied with the look of your poster, check out chapter 4 (“Which”). It offers some essential design principles, and even pointers on how best to hold a pencil. (Not joking.)

If you’re looking for inspiration, savor Caviglioli’s longest chapter: “Who.” These 70+ pages (!) offer dozens of examples where teachers, psychologists, and others show how they use dual coding to teach, persuade, clarify, organize, simplify, and deepen.

As a final strategy, you might check out Caviglioli’s Twitter account: @olicav. Since the book came out, teachers have been trying out his approach and asking for online feedback. The result: a day-by-day tutorial in applying the principles of dual coding to a complex variety of classroom needs.

Closing Thoughts

Because Caviglioli has created a new genre, he makes extra demands on his readers. These pages–although beautiful–can be informationally dense. If you’re like me, you won’t so much read each page as dwell upon it for a while.

In fact, you’ll probably go back to re-dwell on earlier pages as you try to put the pieces together.

My suggestion: be patient with yourself. You might need more time to explore Dual Coding than you do with most books. You might also find that extra time well worth the revelation.