We might be tempted to learn as much as possible.

After all, psychologists study minds in action. It’s hard to think of a topic that might interest teachers more.

Teachers spend all day shaping active minds. Why would we leave any of the discipline out?

Look Here Not There

The invaluable Daniel Willingham has typically thoughtful and practical answers to that question.

He starts by dividing the field into 3 chunks:

Empirical Observations

Theories

Epistemic Assumptions

He argues, in effect, that 2 of those 3 chunks don’t really help teachers do our jobs.

We need to know what empirical observations tell us about learning — especially those well-established empirical observations that are consistently applicable to learners and learning. For example: the limitations of working memory, or the difficulties of transfer.

This information can offer teachers essential guidance on the best ways to help our students learn.

If we overwhelm our students’ working memory capacity, for example, learning simply comes to a halt.

The Limits of Psychology

Although these well-established observations — Willingham calls them “Empirical Generalizations” — help teachers, the other two categories really don’t.

In fact, they might distract and mislead us.

At best, they’re likely to overwhelm our own working memory resources.

For instance: psychological theories not only organize lots of empirical observations. They also make as-of-yet untested predictions about what might happen in other circumstances.

That is, in fact, part of the job of a theory.

However, those untested predictions don’t help teachers. Either we’re aware they’re untested, in which case they don’t tell us what to do (or not to do).

Or we’re NOT aware they’re untested, in which case they might prompt us to try unsupported teaching experiments.

And, epistemic assumptions are typically too broad to be useful.

As Willingham argues, the assertion that “learning is social” leads to differing specific recommendations if you’re a behaviorist or a constructivist.

Beyond the Limits of Psychology: Mental Models

Willingham suggests that teachers need fewer theories and more models: representations of the connections between and among all the empirical findings.

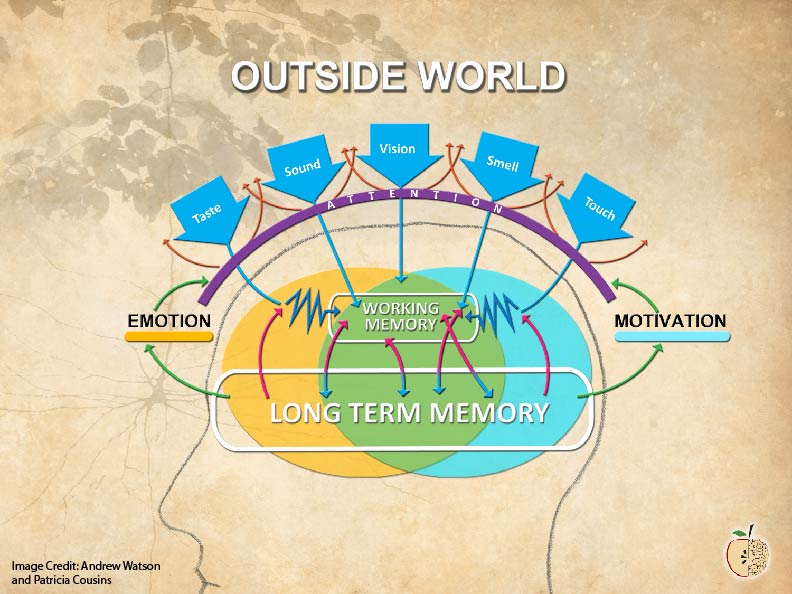

For instance: the image accompanying this article is my own model to represent the relationships among working memory, long-term memory, emotion, motivation, and attention.

That image doesn’t attempt to make predictions, as theories do. Instead, it shows that each of these five topics interacts with all of the others. It suggests that working memory stands “between” the experiential world and long-term memory. It emphasizes the overlap between emotion and motivation as concepts.

Its strives, in other words, to help teachers remember key points about these topics, and to understand the connections among them.

(To be clear, this image draws on the work of many previous scholars — including Willingham.)

A Final Note

Although I agree with Willingham’s broad argument, I do think there’s an important exception. As schools increasingly rely on neuroscience and psychology research to inform our practice, we should have an on-site expert in these disciplines.

Although most teachers should indeed focus on empirical findings, we’ll all benefit if at least one of our colleagues has a rich knowledge of the theories and epistemological assumptions that inform and shape those findings.

As you’ve read here so many times before, our reliance on research brings with it a need for informed and curious skepticism.